This essay first appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly, Issue #5.

When Ambrose Bierce published his Devil’s Dictionary in 1911, he was already an old man. He only had a few years left to live before he vanished into Mexico, reporting on the Mexican Revolution. Like most people, he couldn’t have predicted the manner of his death, though its inevitability was the one certainty he counted on. Fifty years after he most likely perished—against a wall in a small village, perhaps, by firing squad—an optician and amateur photographer and father of three sat his children on a flight of wooden bleachers in north central Kentucky and took their photograph. It would be a simple family photo but for the fact that each of its subjects wore latex monster masks. The monsters look distracted, bored. Maybe the kids wearing them were bored. There were numbers hand-painted in white on the bleachers, about their feet. When developed and printed, the photographer, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, “Gene” to his friends, appended to it the bitterly whimsical title Romance (N.) From Ambrose Bierce #3. It would later become one of his more well-known photographs.

Romance (N.) from Ambrose Bierce #3, 1962

© The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

The Bierce reference may seem arbitrarily chosen, until you seek out a copy of the Devil’s Dictionary to read its own special definition of the word.

Romance (N.): Fiction that owes no allegiance to the God of things as They Are.

Meatyard had a literate eye. When he surveyed his family arranged on the bleachers before him, he saw the fruits of Bierce’s cynicism in ripened form—that is, well past rotting. There is the God of things as They Are, and then there is Another God. The God of things as They Aren’t, but Could Be. For the duration of his short life, Meatyard paid homage to the subtlety of its presence in the world.

But one wonders, what kind of God is this? Another perusal of the Devil’s Dictionary might offer a few descriptions of His Ways and Acts:

Future (N.): That period of time in which our affairs prosper, our friends are true, and our happiness is assured.

Photograph (N.): A picture painted by the sun without instruction in art.

And maybe here, even more pertinently:

Family (N.): A body of individuals living in one household, consisting of male, female, young, servants, dog, cat, dicky-bird, cockroaches, bedbugs, fleas—the “unit” of modern civilized society.

This last entry carries much of the effect of Meatyard’s photographs. The family unit includes vermin—why not? And what’s more, the missing link between children and animals in any given household is its servants. Throughout his life, Meatyard was a family man. He worked six days a week. On Sundays he often traveled the countryside outside Lexington, Kentucky with his wife and children. Nature is never far from his photographs, either in the form of weeds and trees or in the return of dilapidated houses and barns back to a state of raw matter. Everything he depicted was an expression of nature. So it’s interesting he’d do so with gallows humor and a taste for the enigmatic.

Bierce’s entry for the Future is relevant here as well. After twenty-two years as a practicing photographer, Meatyard died of cancer in 1972, a week short of his forty-seventh birthday. This would be sad information, if it weren’t the case that Meatyard was luckier than most: for those twenty-two years he was by all accounts fortunate, a loving father to his children, husband to a supportive and artistically appreciative wife, a businessman successful enough to open his own store, Eyeglasses of Kentucky, in 1967. He was a man not short on friends; and the friends he did make were integral to the development of his art: Van Deren Coke, Thomas Merton, Jonathan Williams, Wendell Berry, Guy Davenport, Emmet Gowin. Through Davenport, a champion letter writer with over two hundred correspondents, he met the likes of Louis Zukovsky and Hugh Kenner. Though the future wasn’t generous to him, the present moment was fuller than he could have hoped for.

As for the proposition a photograph is little more than a painting made by the sun without instruction in art, in Meatyard’s case, even this seems appropriate. His manner of working was a curious mix of theater direction and unfussy spontaneity. Many attest to his subtlety when photographing human subjects; he moved about casually and rarely made a point to worry over framing. He worked quickly then moved on. So this was the artifice at hand: to emulate the ease and unintrusiveness of nature, to dissolve one’s own presence into the background. This element of self-effacement was a conscious value for him. In letters to the publisher of his last project, The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, and again in a lecture he delivered in Louisville the year of his death, he described the effect he hoped to create through the use of masks. To wear a mask is to efface one’s individuality, to reveal what is always the case—that all living beings, human or non-human, are interconnected, subtly vibrant instances of sentient consciousness in the flow of matter into and out of form. His readings on Zen most likely informed this inclination. What is engaging about the photographs themselves is the dramatic effect they still have. No doubt there have been photographers who have used masks before Meatyard did, but there is a quality to the outcome that might prove surprisingly difficult to replicate—a mixture of ambiguity, paradox, and grotesque humor, which in the combinatorial instant of the developed photograph proposes a metaphysical inquiry into the unlikeliness of everything that is. One thinks of Kafka’s aphorism: “What is laid upon us is to accomplish the negative; the positive is already given.” Masks, dolls, mirrors, old buildings, arbitrary junk arranged with such care it constellates into a kind of poetry. So then, what’s to be done but to turn facts against each other, to strike one plain object against another until it sparks connotations that wouldn’t have otherwise been apparent? There’s also the matter of John Szarkowski’s observation on the photographs of William Eggleston: “The photographer hopes, in brief, to discover a tension so exact that it is peace.” And this is precisely what is distinct about Meatyard’s tableaux arrangements now, more than fifty years after the photographs were taken: Their details are held in such a taut relationship against each other, the ambiguities they render remain irresolvable.

The unlikeliness that someone like Gene Meatyard could become a major—though albeit still a somewhat fringe—art photographer seems, from the vantage point of fifty years after his death, integral to the photographs themselves. But hasn’t that often been the case? The avant-garde tends to grow in the dark, like mold. It spreads at its own pace and creates a body of work that can prove alarming to the casual observer, once discovered.

People who are born in places like Normal, Illinois, who work as opticians for a living, who take photographs on family trips to the country on Sunday afternoons rarely acquire a knowledge of their craft shaped by the force of obsession. If that does happen, though, the more amiable and unassuming such people are, the better. Should their family photographs double as art, this is accomplished with a certain humility. Most often they will be less concerned with the construction of an artistic persona than in diagramming and participating in the unreality of existence, via allegory. This is a generalization, of course. There’s only one person from Normal, Illinois who could have created these kinds of photos. Their inevitable qualities seem to emerge from the unlikely inevitability of the person who took them.

Meatyard bought his first camera in 1950 after the birth of his son. At the time he worked for a company which also sold photographic equipment—so it was convenient, his buying the camera. As often happens, what began innocently as a hobby soon, through a mixture of play and habit, became a vocation. In 1954 the Meatyard family moved to Lexington, Kentucky. It’s a decision that brought him some luck. In the mid-fifties there were camera clubs in many mid-sized cities across America, but the Lexington Camera Club was more accomplished than most; the Club’s president, also at the time the president of his family’s hardware company in downtown Lexington, Van Deren Coke, was a major photographer in his own right, an art historian and curator. It was through Coke that Meatyard acquired a kind of informal education. Coke brought him to a photography workshop at Indiana University, introduced him to Minor White and Aaron Siskind. From a reading list Minor White distributed during that visit, Meatyard discovered Zen philosophy, which would later figure prominently in his general outlook. This also started a trend that continued for the rest of Meatyard’s life: Follow up on any and every reading suggestion, read widely.

What would have become of Meatyard if he’d stayed in Normal, working at the Gailey Eye Clinic? If he’d never met Van Deren Coke or, later, Guy Davenport? When he walked into a Woolworth’s one afternoon in the late fifties, would he have thought enough of the latex masks dangling on a display rack, to buy them? When he was a young boy, his father had renovated historical homes. But if he hadn’t moved to Lexington, would he have taken his family for drives around the country, stopping at the sight of old abandoned houses, getting out of the car to explore them?

Limitations, as well, provide a kind of traction. If a person only has one day a week to practice their art, that one day will bear the charge of the other six days spent away from it. So the strictures of Meatyard’s responsibilities set the pattern that would last for the rest of his life: He would involve his wife and children in this art-making compulsion of his, would drive them out to the countryside around Lexington in search of old dead farmhouses and barns. He would arrange them into weird static film stills that would suggest more than the sum of their visual facts at hand. A man with a prosthetic arm standing next to a mirror and a headless, armless mannequin. A child wearing a monster mask waving his arms until they dematerialize into white blurs.

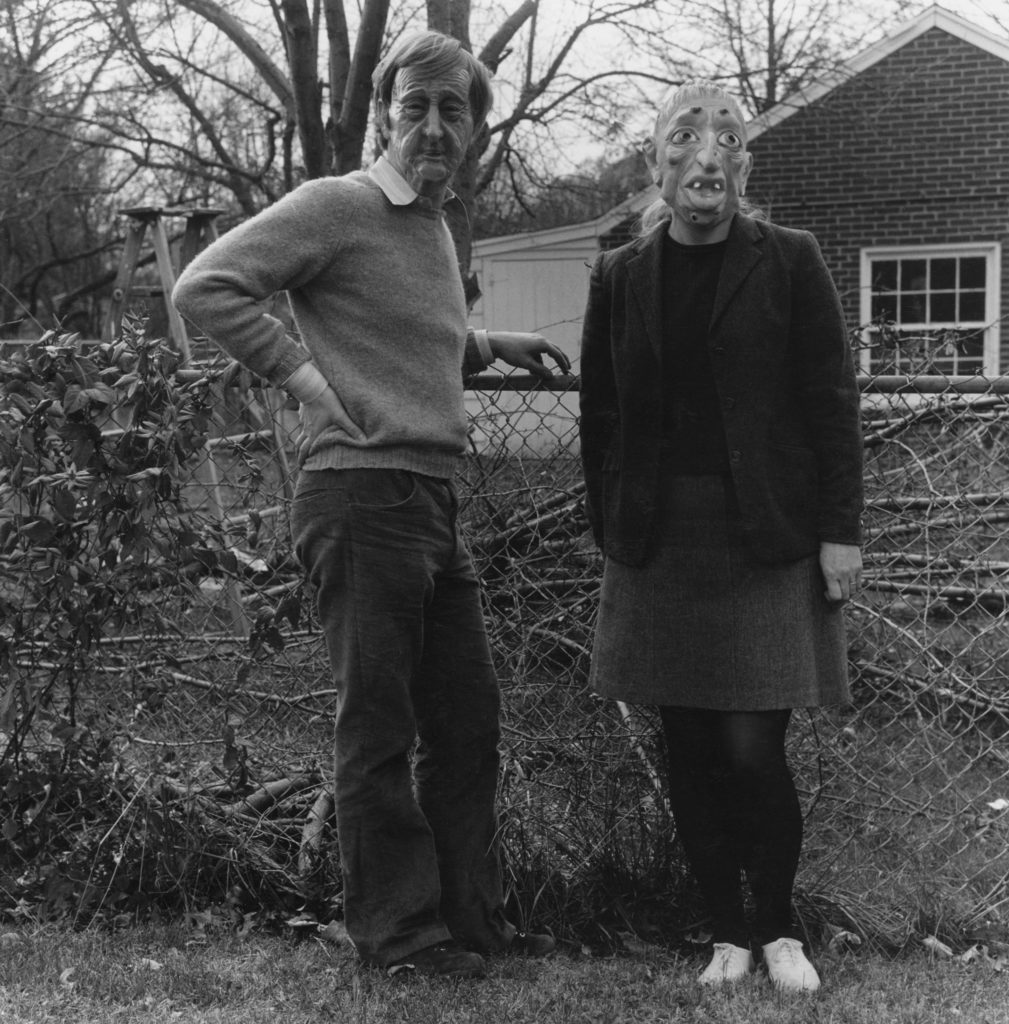

Lucybelle Crater and photo professor Lucybelle Crater, ca. 1970–72

© The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

•

Allegories—but for what? On these trips he took hundreds of photos but left most dormant in their rolls, sometimes for years. The images needed to rest incognito as negatives for a while, it seems, to not suffer a premature magnification by light. In an essay written after his friend’s death, his neighbor Guy Davenport put it this way: Gene developed his negatives only once a year, to avoid being tyrannized by impatience. But it was also the case that he was a busy man.

His sons’ names were Christopher and Michael; his daughter and wife were Melissa and Madelyn. Like Spinoza, he ground lenses for a living. It’d be too tempting to not call attention to the plain fact he improved people’s eyesight, making glasses to fit a variety of different faces, or that he hung his own photographs on the walls of his store, for viewing by his customers. One can only imagine what they thought of them. In the same essay where Davenport eulogized Meatyard’s patience, he offered an even sweeter assessment of the man, his good fortune and the enigmas he unearthed from it: “He had invented himself, with his family’s full cooperation.” Now how often could a sentence like that be written, about anyone?

Still, there were low points. When the 1964 edition of Beaumont Newhall’s History of Photography was published, Meatyard was let down. His work hadn’t been included in the monograph and it depressed him. His solution? Tack a print of one of his photos onto the frontispiece of his copy, Romance (N.) From Ambrose Bierce #3. What other evidence does one need for the subtlety of his humor? His work bore no allegiance, it seems, to the gods of validation and career-making. But why should he have cared? It’s touching that he did, though. He’d had a heart attack in 1961 and had given himself ten years to take his eye the furthest it could go. And it says much that many decades later someone should invest hours of their own life to write about his own.

After his death, he was pigeonholed as a regionalist. The general prejudice against amateurism asserted itself, and he was spoken of as a kind of primitivist. A writer for the New York Times referred to him, predictably, as a “backwoods oracle.” Such is the fate of an original talent with a home address in the American South. No matter that Meatyard himself couldn’t relate to the self-styled kitsch of Southern regionalists. Like Davenport, he braced at being reduced to a category other than “Modernist.” Besides, it could be seen to be the case that advanced artists who live at the edges of “high” culture are at a distinct advantage. Making use of what’s around them, they stand a better chance of discovering more novel combinations, because by and large they are surrounded by an undocumented world.

One only needs to read about Meatyard’s conceptualist framing of his work to understand the level of sophistication at play. The primary inspirations for The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater were two-fold: Gertrude Stein and Flannery O’Connor. From O’Connor’s story “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” he took the name, Lucynelle Crater, and repurposed it for his own use. From Stein’s The Making of Americans, he took the concept of repetition as both a form of insistence and a means of hermetic elaboration. In the fictional family album, which he created during his last two years when he was dying of cancer, over the course of sixty-four images he depicts his heroine, Lucybelle Crater, posing for photographs with various friends and family, each of them as well named Lucybelle Crater. The caption for each photo reads like a deadpan jape. “Lucybelle Crater + 11 yr. old daughter Lucybelle Crater,” “Lucybelle Crater and her regular Mother Lucybelle Crater.” To know the history of the book’s construction adds an element of poignancy to the humor. In each photograph the woman wearing Lucybelle’s hag mask is Meatyard’s wife, Madelyn. The other subjects in each photograph wear a semi-transparent plastic old man’s mask. The first photo in the series depicts Meatyard and Madelyn posing as Lucybelle and her husband. The photos that follow portray Lucybelle with one of Meatyard’s many actual friends or acquaintances, each transformed into faint doubles of each other; all of Lucybelle’s friends and family not only share the same name but the same face, it would seem; each are horribly aged, no matter how young they are. The final photo in the series enacts a sleight-of-hand inversion: The Lucybelle mask is worn by Meatyard himself, while his wife Madelyn has become the old man. In the end, gender roles are switched; through the force of the album’s repetition, its author has become its heroine. The transformation is emblematic of his art and in certain ways marks the terminal point of his methods. When asked about the masks, he insisted they were a means of hiding the differences between people, of emphasizing or revealing the interconnectedness between them. This is all fine and good; but then why did the masks have to be so ugly? To be a creature in the flesh is to know where that flesh will go, and what will happen to it along the way. So it means much that he would include many of his closest loved ones in this final project.

To consider Meatyard anything less than an artist above all claims of regionalism would be to sell him far short of his accomplishment. But then one considers Flannery O’Connor’s essay, “The Grotesque in Southern Literature,” which served as her means of complaint against the appellation of Southern Artist, as well as, paradoxically, her attempt to claim certain ambitions for writers caught in such a cheaply minted category. To conclude any word on Meatyard with an excerpt from this short essay wouldn’t be the worst thing. It might even be a means of exploding into clearer view one’s sense of what he was after, in his photographs:

. . . if the writer believes that our life is and will remain essentially mysterious, if he looks upon us as beings existing in a created order to whose laws we freely respond, then what he sees on the surface will be of interest to him only as he can go through it into an experience of mystery itself. His kind of fiction will always be pushing its own limits outward toward the limits of mystery, because for this kind of writer, the meaning of the story does not begin except at a depth where the adequate motivation and the adequate psychology and the various determinations have been exhausted. Such a writer will be interested in what we don’t understand rather than in what we do. He will be interested in possibly rather than in probability.

Thousands of Meatyard’s photographs still remain in their rolls, undeveloped. So talk of possibility here is two-fold. That they’ve yet to be seen seems appropriate. That the majority of his work would remain in the negative, something he could’ve predicted—a natural outcome of what he was looking for.

•

These and other photographs by Ralph Eugene Meatyard were on display at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco from March 9 through May 6, 2017 as part of the exhibit Ralph Eugene Meatyard: American Mystic. The exhibition was a rare opportunity to view both iconic and lesser-known photographs by Meatyard alongside the artist’s notebooks and annotated volumes from his personal library. The exhibition coincided with the publication a major new monograph on the artist by the esteemed art historian Alexander Nemerov.

Kyle Coma-Thompson is the author of the short story collections The Lucky Body (Dock Street Press, 2014) and Night in the Sun (Dock Street Press, 2016). The title story for his first book was included by Ben Marcus in the anthology New American Stories (Vintage, 2015).

This post may contain affiliate links.