[The American University in Cairo Press; 2017]

[The American University in Cairo Press; 2017]

“I do not know what I would have done without this Diary. My companion, Oh loneliness, oh love, oh bloody bloody bloody misery.” – Waguih Ghali.

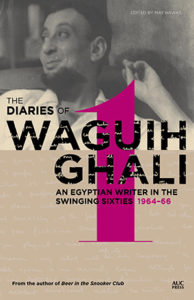

Very little is known of Waguih Ghali, the Egyptian author of the much loved but little known Beer in the Snooker Club. The novel — Ghali’s only major piece of work — was published in 1964 to critical acclaim, and Ghali subsequently took his own life in 1969. While the novel went out of print for a period of time, it was republished by Serpent’s Tail in 1987, and has slowly built a strong cult following among Arabic Literature aficionados. Reading the book in 2012 over the course of a few days, I fell in love with and was quickly transformed by Ghali’s simple but profound writing style, which is simultaneously heart wrenching and humorous. As a young writer, the novel was the single biggest influence on my writing — in fact, Guapa is peppered with references both to Beer in the Snooker Club and to its elusive author.

Yet apart from a couple of photographs, and Diana Athill’s memoir, After a Funeral, which chronicles her turbulent friendship with him, very little else is known about Ghali. The AUC Press’s publication of his diaries (in two separate volumes), written in the last few years leading up to his suicide, is therefore a much welcome addition, and has been long-awaited by his small but devoted followers.

The first volume covers the years 1964 to 1966, and centers on Ghali’s time in Rheydt, Germany, while working with the British Army. It is worth noting that Ghali had requested Diana Athill to publish the diaries posthumously, Athill never did, and has expressed that she found them to be “the depository for all that was most hopeless and neurotic in poor Waguih’s life.” In this, she is certainly not wrong. The character that shines through in these diaries is certainly self-indulgent and miserable; but he is also funny, charming, romantic and warm, regularly hosting friends, and happiest when he is listening to music, drinking wine, and cooking meals for others.

The diaries are mainly focused on Ghali’s battle with depression and anxiety, his doomed love affairs, and his alienation from Germany and German society (“The more I stay in this country, the more I want to vomit on the population in general”). He drinks, he gambles, he obsesses over his emotions, and he sleeps. Occasionally he writes, but more often he struggles to write through the depression (“the cafard”). When he finally seeks professional help, the doctor he visits does not take his depression very seriously, telling him that “people in West Germany don’t, as a rule, suffer from such things.”

Most surprising about the diaries, perhaps, is their darkness. This is a headfirst dive into the mind of a tormented man. The long, descriptive passages on depression can be difficult to read, particularly with the knowledge that, for Ghali at least, there will be no happy ending. As someone who struggles with mental health issues, I read the diary entries with the terror of recognition; the knowledge that there would be no light at the end of the tunnel only adds to the despair. We know how Waguih’s story ends. We know that there is no redemption. This can make the diaries difficult to read, and I can understand Athill’s decision not to publish them.

During one of Waguih’s later entries, he writes:

I am gripped by a strange fear . . . It is something like the fear of darkness and seeing no ray of light and knowing no ray of light will manifest itself. Fear mingled with despair at this deep darkness, which you feel is lasting and cannot be overcome. I find myself shaking all over. I clench my muscles now and then. All noises irritate me, even footsteps upstairs. A voice, a musical note on the radio emanates a feeling of revulsion in me. This fear increases and I reach a state of intolerable hopelessness . . . I seem to shrink, physically, within myself, trying to make myself as small as possible.

Reading passages such as these, I often found myself wondering whether the passages on depression could be considered beautiful. There is no doubt that the writing is powerful, but is it possible to call a piece of writing “beautiful” when it ignites in the reader such intense feelings of despair? This question stayed with me long after I put the book down, and I wonder whether Athill herself answered this question by deciding not to publish the diary.

Yet within this inner turmoil, there are moments when the Ghali who wrote Beer in the Snooker Club shines through: he is witty, cutting, often judgemental, and sometimes laugh-out-loud funny, that perfect mix of “sad and funny” that made Beer in the Snooker Club so memorable (“As I said, I am penniless, lazy, sleep over twelve hours a day, can’t bear to think of the future, but I am advising the Germans to form a new political party . . . I can see the ridiculousness of it all.”). Ghali can be both funny and scathing in his judgements, though he reserves his harshest judgements for women (he reduces one woman to a single description: “a nice-looking, fattish sort of semi-cow”).

The diaries also shed light on Ghali’s conflicted relationship with writing: in many ways, ‘the writing’ becomes a cause and cure, a source of pain and the only solace to soothe the suffering. Ghali is anxious about not writing, about his “dissipated potentialities.” And yet in the rare times when the writing flows, it becomes his salvation. “I am slowly entering my cocoon, and when I am in it, I am alright.” Writing becomes, paradoxically, both an exorcism of his demons, and a refuge from them.

In some ways, the subtitle of this volume “An Egyptian Writer in the Swinging Sixties” is misleading. The only thing swinging in this diary is Ghali’s mood. In the moments of political and intellectual observations, Ghali is brilliantly astute: his brief but poignant observations of Germany in the 1960’s paint a vivid picture of a traumatised society struggling with its lingering Nazi sympathies. His throwaway comments about literature are very telling: He was a fan of Saul Bellow and Russian literature (Tolstoy and Dostoevsky), not a fan of Kingsley Amis (“One Fat Englishman . . . one fat stupidity of a book”) or V.S. Naipaul (“too engrossed with himself, his feelings, his thoughts which should only be a concern to himself and not expect others to feel.”). Beyond this, those hoping for Ghali’s political or literary insights, or a glimpse into the intellectual crowds of the 1960s, will be disappointed with this volume.

What this volume does offer, however, is an anatomy of loneliness, the writing process, and mental illness. It is a heart-breaking and harrowing journey into the frustrated creativity of a unique and unforgettable man. At one point, Ghali quotes Nietzche who once said ‘if you are aware of yourself, you are not a person.’ He goes on to write: “The fact remains that I am not a person. I rely on other people to make a person of me. I try and make a person of myself in other people’s eyes.” With the publication of his journals, May Hawas and AUC Press have helped make a person of a little known but much loved cult hero of Arab literature.

Saleem Haddad is the author of the novel Guapa, published in 2016 by Other Press (US) and Europa Editions (UK).

This post may contain affiliate links.