This interview with Paul Devlin, scholarly editor of Albert Murray’s work and a writer, was originally published in three parts from July 18-23 as part of Full Stop’s Albert Murray Week, a celebration of the late author’s centennial, which also included excerpts from Devlin’s Murray Talks Music and a review-essay on “Murray and the Americas” by Matthew St. Ville Hunte. Presented here is a condensed and lightly revised version of the interview with Devlin. The original version is still online.

Since then, the following has occurred in relation to Murray’s centennial year: the Library of America’s edition of Murray’s nonfiction and memoirs was published in October and greeted with a glowing review by Dwight Garner in the New York Times, co-editors Devlin and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. were interviewed for Publishers Weekly, Murray Talks Music was reviewed in the New Yorker, and the Albert Murray Trust launched AlbertMurray.com. On November 28th, the 92nd Street Y will host a celebration of Albert Murray featuring Devlin, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Renata Adler, Wynton Marsalis and Ayana Mathis. Also, an interview that Gates and Robert G. O’Meally did with Murray in 1978 will be published in the winter issue of The Paris Review (#219).

Discussed in this section: the Murray revival, Thomas Chatterton Williams on Murray, Nate Chinen on Murray, the forthcoming Library of America edition of Murray’s nonfiction, some of the artists Murray influenced, The Omni-Americans, identity, idiom as identity, the blues idiom statement, Murray’s relationships with James Baldwin and Gordon Parks, jazz and America’s postwar influence, Murray in Morocco in the 1950s, and jazz as diplomacy.

Paul Devlin is a leading scholar of Albert Murray’s work and a scholar of American literature and culture in general, as well as a freelance critic. He is the editor of Rifftide: The Life and Opinions of Papa Jo Jones, as told to Albert Murray (2011) and of the new book Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues. With Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Paul is co-editing the Library of America’s edition of Murray’s essays and memoirs, forthcoming in October. Paul earned his Ph.D. in English at Stony Brook University in December 2014 (his dissertation was on Murray, Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, and Percival Everett). He has written for Slate, The Root, Bomb, The Daily Beast, Popular Mechanics, San Francisco Chronicle, The New York Times Book Review, and many other publications, including scholarly journals. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle, Jazz Journalists Association, PEN American Center, and The Authors Guild, and is an appointee to the MLA’s Committee on the Literatures of People of Color in the United States and Canada.

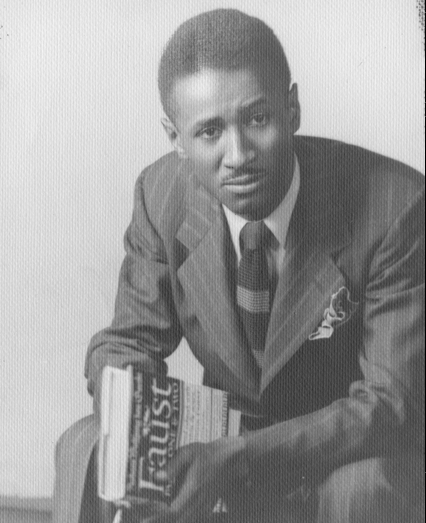

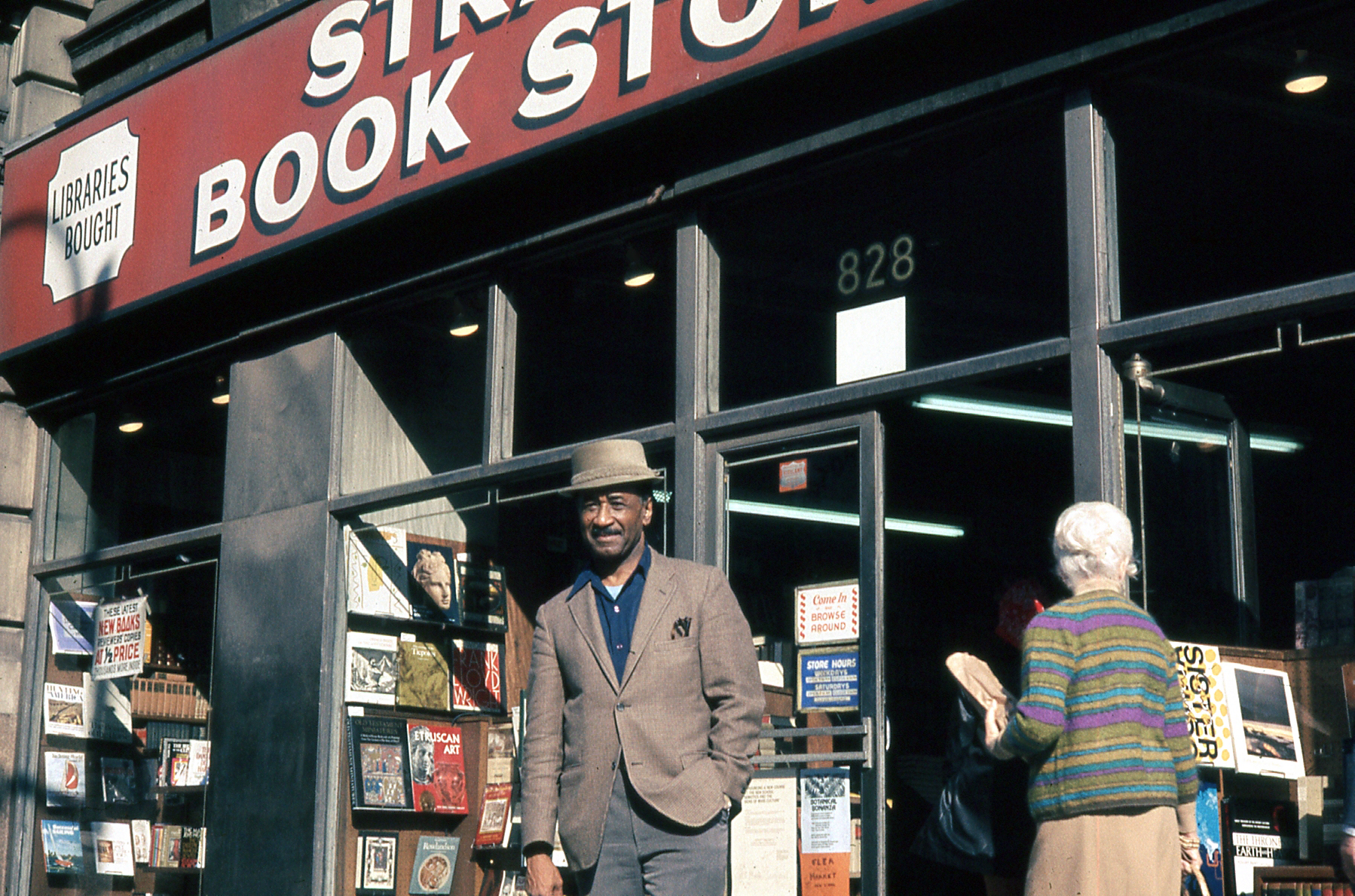

Albert Murray (1916-2013), whose work is an American treasure, was one of the most original and incisive writers and thinkers of the twentieth century. With a signature balance of humor and erudition, he created what he felt were accurate literary representations of the African American experience, while counter-stating sociological narratives of victimhood and pathology. He saw it as his duty to relay black life as he knew it, with its wit and wisdom, its heroism and elegance. He wanted non-black Americans to be aware of how much African American culture informs their identity. But he also had an expansive, inclusive vision of the “Omni-American,” a person whose identity is the synthesis of many traditions, and who, for Murray, is well prepared for the modern world. In 1996 he received the National Book Critics Circle’s Ivan Sandrof Award for lifetime contribution to American arts and letters. After retiring as a major in the U.S. Air Force in 1962 he wrote twelve books: The Omni-Americans (1970), South to a Very Old Place (1971), The Hero and the Blues (1973), Train Whistle Guitar (1974), Stomping the Blues (1976), Good Morning Blues: The Autobiography of Count Basie (1986), The Spyglass Tree (1991), The Seven League Boots (1996), The Blue Devils of Nada (1996), Conjugations and Reiterations (2001), From the Briarpatch File (2001), and The Magic Keys (2005). He also helped create content for four more books: Conversations with Albert Murray (1997), Trading Twelves: The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray (which he co-edited, 2000), Rifftide (2011, edited by Devlin) and the recently published Murray Talks Music (2016), a collection of his previously unpublished and uncollected interviews and writings on music, which has an introduction by Devlin, a foreword by the eminent critic and biographer Gary Giddins, and an afterword by cultural critic Greg Thomas. Full Stop is running three excerpts this week, but here is a brief one the publisher ran in May. Devlin talked with Full Stop over a period of weeks from May through July 2016.

A.M. Davenport: Paul, this year is Albert Murray’s centennial. I recently read Thomas Chatterton Williams’ review of Murray Talks Music in the spring books issue of The Nation, in which he praises Murray for his contributions to American letters, yet describes Murray as a writer who is “not household familiar.” Williams goes on to praise the book for its collection of previously unpublished and uncollected material, and for your extensive introduction, which he calls “worth the price of admission” alone. Nate Chinen, in the arts section of the New York Times on May 21, called Murray Talks Music “insightful,” and he used it brilliantly as a frame for a long review of new jazz albums. “Mr. Murray’s legacy,” Chinen writes, “is now largely understood in musical, as well as literary terms.” Let’s talk about Murray’s legacy. We need his work now as much as we ever have. You and a number of other intellectuals are working to bring it back into the public discourse. Am I right in thinking that there seems to be a kind of revival of interest in Murray’s work?

Paul Devlin: Yes, there is a revival underway, and I’m so glad to see it happening, because I’ve worked hard for Murray’s legacy for several years, alongside Murray’s literary executor, Lewis P. Jones. The essays you mention in your question are outstanding. Murray’s ideas are circulating again and a lot of people are realizing he was onto something. The reception of Murray Talks Music was a thrill. In October the Library of America will publish the definitive edition of his collected nonfiction, co-edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and me. Some of Murray’s books had been out of print, but now they’ll be available in perpetuity, and annotated for the first time. I hope the volume will do for his literary legacy what Chinen suggests Murray Talks Music may be doing to cement his legacy as a thinker about music. Also, a few unknown essays — some of his best — will see the light of day in the Library of America edition. The 92nd Street Y will be doing a tribute to Murray with a reading of his work on November 28, featuring Renata Adler, Ayana Mathis, Wynton Marsalis, Gates, and me. This past February there was a symposium at Columbia University on his work, featuring scholars from around the country. It was the coldest day of the winter in New York, with especially biting winds, but the venue was full, with people standing in the back. I organized a special session on his later fiction at the MLA convention in Austin earlier this year. Jazz at Lincoln Center and the National Jazz Museum in Harlem hosted readings and discussions. There is an event in the works at Harvard for next spring and there are several other projects in planning stages. There is a burgeoning sense that Murray’s work is central to understanding American culture, along with, dare I say, the human proposition.

About how long have you researched Murray’s work and how has the revival unfolded?

Murray was my mentor. We met in 2001, when I was an undergraduate in college. We quickly became friends and I became an assistant to him. I’ve been studying his work as a scholar for almost that entire time — along with studying plenty of other writers, movements, periods, and so on. Two and a half of the six chapters in my dissertation are on his work. When he died in 2013, at 97 (after some years of health problems) I was overwhelmed by the tributes in online publications and on social media (I link to some of them in this guest post I wrote for Ethan Iverson’s blog.) But the revival, in a sense, began just before that: I’d say 2011, when I transcribed, edited, and annotated the interviews he did with the jazz drummer Papa Jo Jones into a well-received book (Rifftide). I’m measuring the revival from there, because getting it published was an epic, uphill battle. Uphill doesn’t do it justice — it was like a battle up a sheer cliff side! After many rejections by academic presses and trade presses, I was almost ready to give up when I pitched Minnesota, where there was a vision for the book and wisdom about how to proceed with it. There was a lot of good publicity surrounding the book when it was published, despite a lot of deer-in-the-headlights-ism typical of many media elites. It got an enthusiastic review in the New York Times Book Review. The review in Library Journal is brilliant. I went on the Leonard Lopate Show on WNYC and on Josh Jackson’s show on WBGO. Shortly thereafter, a portion of Murray’s art collection was exhibited, and that got attention too. (I wrote the wall text for the exhibition. I’d already published a book chapter on Murray and visual art.) In Spring 2013, a few months before Murray died, two major essays on his work appeared: by Walton Muyumba in Oxford American and by James Marcus in Columbia Journalism Review. The Schomburg Center did a tribute in late 2014. Ayana Mathis argued in a superb back-page essay in the New York Times Book Review in January 2015 that there should be a biography of Murray. Her essay got a lot of attention. I got a bunch of queries out of the blue. Murray Talks Music had already been under contract for a year at that point. That’s the outline of the current revival.

I should note that Murray was never really “forgotten,” but there is a bit of a paradox in that while he continued to receive awards until 2012, there was a steep drop off in fan letters, scholarly queries, and speaking invitations after 2005, when his health began to decline — and it’s not as if the state of his declining health was public knowledge. He received the W.E.B. Du Bois Medal from the Du Bois Institute at Harvard in 2007. Gates bestowed the award in a ceremony at Murray’s apartment. There was a notice about it in the New York Times. In 2010 he was included in a New York Magazine photo essay on prominent New Yorkers over 90. The first academic essay collection on his work was published in 2010 — but it didn’t really get reviewed until 2013, except for the briefest of mentions. It was published right in the nadir of interest in his work and was greeted by crickets. (But there was a nice event and panel discussion for it, which I organized, at Jazz at Lincoln Center.) By 2008, his hearing was nearly gone. He used a device in which a person would speak into a microphone and he’d hear the voice in headphones. It kind of worked, sometimes. Sometimes he’d prefer near-shouting, so he could really make the words out. Often writing questions on a notepad worked best. Visitors were sparse. I visited regularly, sometimes with the writer Sidney Offit, one of Murray’s oldest friends. Lewis Jones and his family visited regularly. Others visited from time to time. But there was an unmistakable lull in interest in his work, from say, late 2007 through late 2011, despite awards and the essay collection. There were no thoughtful essays, like those by Muyumba or Mathis in prominent venues, to generate intellectual discussion.

Is this the first revival? His books from the 1970s seemed to have taken on a new life in the 1990s.

There were previous revivals. An article in Kirkus Reviews in 1995 mentions a Murray revival underway. The writer had it right, as that piece presaged an avalanche of attention and accolades in the late 1990s. There were revivals in 1982-83 and 1989-90, when some of his books from the 70s came back into print. Revivals come and go, but I have a feeling this one will be permanent. One bonus of the Library of America edition, in which all of his nonfiction is collected in one volume, is that people who know him mainly as a social critic, say, as the author of The Omni-Americans, or mainly as the author of the treatise on jazz, Stomping the Blues, or of the memoir/meditation on the south, South to a Very Old Place will also see and have the other books between two covers. Interest in his work has often been compartmentalized. Someone working in Southern Studies may think of South to a Very Old Place as his big book. Someone in Jazz Studies might think of Stomping the Blues as his big book, and so on. A lot of things had to fall into place and incalculable toil went into getting all those books into one edition, but here we are, and it’s a marvelous development — not easy to imagine ten years ago!

We know from the books you’ve edited that Murray enjoyed lasting relationships with a wide circle of artists, musicians and intellectuals. These relationships serve as yet another piece of the legacy he has left us with. Who are some of the men and women he influenced?

He influenced a large and diverse group of writers, thinkers, musicians, and artists, from Elizabeth Alexander and Toni Cade Bambara to Ravi Howard and James Alan McPherson. Some very serious people sought his wisdom and he generously obliged: Charlayne Hunter-Gault, David Murray, Melvin Dixon, Tom Piazza, Clara Maxwell, Leon Forrest, Melvin Edwards, Ernest Gaines — among so many others. He was a mentor to Robert G. O’Meally, who founded the Center for Jazz Studies at Columbia University. He was a mentor to Loren Schoenberg, who founded the National Jazz Museum in Harlem. He was a mentor to Wynton Marsalis and Stanley Crouch, with whom he co-founded Jazz at Lincoln Center. Gary Giddins wrote a profound testimonial to Murray’s mentorship in his foreword to Murray Talks Music. Another prominent acolyte was Skip Gates, my co-editor of the Library of America volumes, who is a grand-scale institution builder, preeminent scholar, award-winning filmmaker, and familiar figure on PBS.

What’s behind Murray’s idea of the “Omni-American?” More than anything else in the last few years, that theory has shaped the way I view our cultural identity.

Murray railed against what he called “the folklore of white supremacy and the fakelore of black pathology” — these narratives obscure(d) the reality of American life. An Omni-American is open to and formed by all influences, but from a foundation formed from black, white, and Native American cultures. Murray saw African American life as intrinsically heroic and intrinsically modern — that is to say, it is at the vanguard of modernity because of historical circumstances, and thus, the most American aspect or component of American identity. Murray said that the most ardent white supremacist in the South has much more in common culturally (and possibly even genetically!) with his or her black neighbors than with some distant relative in Europe — and thus should think of him or herself as an Omni-American. It is an inclusive and pluralistic vision of culture that accounts for history, economics, and individual choice or agency. Americans are “Omni-Americans” one way or the other, and so it’s better to not pretend otherwise. Elizabeth Alexander wrote a poem called “Omni-Albert Murray,” and she had the right idea, but the idea is also for Omni-Everybody. He was not the only Omni-American and there is no one perfect way to be an Omni-American, but the thing that is wrong and untrue is ethnic supremacism of any kind.

Murray despised what he called “racial mysticism” and spent decades trying to counter it at every turn. The “Omni-American” idea is a conception about the complexity of human life and culture and how it actually works and evolves. It is a necessary corrective to identity politics, which perhaps at one time were a vehicle to promote diversity and equal opportunity, which was good, and I suppose it can still have that use, but have lately been co-opted in the most cynical and pernicious ways, and have even become a sort of identity-hectoring in some quarters, especially when used for political deflection. Identity, for Murray, is idiomatic, which is to say cultural, and not genetic. Murray said people choose their own ancestors to go with their real ancestors. Ellison may have said that too, but Murray got the idea from a poem by W.H. Auden in the 1930s. He chose James Joyce and Marianne Moore and Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, Auden and Thomas Mann and James Weldon Johnson and Duke Ellington — and many others, including his own ancestors, whose labor in the cotton fields of Alabama he deemed heroic. He also viewed escape from slavery as heroic.

At this moment, there is a surge in ethno-nationalism around the world — a hideous development. It has been occasioned by politics and economics, but more significantly perhaps, by a worldwide decrease of emphasis on education in the humanities, which results in less critical thinking. Murray’s work undermines both exclusionary ethno-nationalism and the appropriation of identity politics for the purposes of deflecting other discussions about equality. If Murray’s work had caught on decades ago the entire political landscape of 2016 could be different. I have critical distance from Murray’s work, and a critique of certain aspects of it, but make no mistake: his ideas are an antidote, or a part of an antidote, for so much of what’s gone wrong in the United States over the past few years. He declared American culture to be “incontestably mulatto” and supported that thesis with one of the most swashbuckling essay collections ever: The Omni-Americans. The Omni-Americans should be taught at police academies, state trooper academies, and places like say, UC Santa Cruz and Bard College. If every police academy in the United States had started assigning The Omni-Americans twenty years ago, we’d live in a much better country today.

Police academies?

I’d be happy to do seminars for police groups. I have a hunch they’d dig Murray. He was a realist: he said “the fire next time” will be put out by next Wednesday! He loved America, thrived in the Air Force, and celebrated the possibilities in the American experiment. He had a heroic sense of life. But what his work offers is a radical reorientation of perspective on culture and American history. I think it could make a real difference. There is a certain type of police officer — and this goes for people in other professions as well — who gets carried away with power, pride, and arrogance, sometimes for simply being employed. In this stagnant economy, a steady paycheck can make a person of a certain personality type feel somehow anointed. Combine that with exclusionary race pride and it can become truly toxic — as we see on the news almost every day. These particular officers — and of course it’s not nearly all — need to understand that black youth is not “the other” and not the enemy. If Darren Wilson had read The Omni-Americans and then passed an exam on it, it’s hard for me to imagine that he could have used such dehumanizing rhetoric against Michael Brown. And without that rhetoric, how would his conduct have been different? Who knows — I think there would have been a different outcome to the situation. And I know police officers will say “you wouldn’t believe what we see out there.” Fair enough — people do crazy things. But police in homogenous societies would probably say the same thing. It shouldn’t be an excuse for more havoc. Protecting law-abiding people from criminals and not arbitrarily combining them should be the first job of the police. An enemy of every police department is widespread distrust of police and their motives, and subsequent tensions. Yet that seems to be what too many have been creating of late. Perhaps some join the force with every good intention and get overwhelmed. It would be good to get a new perspective. Walker Percy wrote of The Omni-Americans, in a long and perceptive review-essay in Tulane Law Review, “show me a book about race and the United States that fits no ideology, resists all abstractions, offends orthodox liberals and conservatives, attacks social scientists and Governor Wallace in the same breath, sees all the faults of the country, and holds out hope in the end–then I have to sit up and take notice.” I hope many will continue to take notice.

I hear you. But what if people read it and reject it?

Even those inclined to disagree with Murray would be compelled to tip their caps to his inexorable logic. Some discourse on race, especially on the internet or whatever, can sometimes have a scolding tone and maudlin attitude. Murray’s work is free from that. As Jack Point says in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Yeoman of the Guard, “I can teach you with a quip if I’ve a mind; I can trick you into learning with a laugh.” Not that Murray was a comedian, not that he was out to make jokes — but he’s able to treat heavy ideas with a perfectly timed light touch, and has a knack for a kind of comic relief by throwing the absurd into stark relief. There’s a lot to be said for methods of delivery. (And by that I don’t mean to imply that I’m in favor of the canard that academic discourse should always be clear and well-written.) So, it’s not as if Murray’s style is simple or anything, far from it, but I think people can relate to his tone. That’s one thing Murray implies about Lyndon Johnson in South to a Very Old Place (in the “Mobile” chapter) — his idiomatic discourse went a long way toward getting Civil Rights legislation passed.

Just what is it about Murray’s conception of American identity that has so much political potential?

For a lot of people it’s like a lightbulb going off. And it’s all so deft, and argued with such formidable intelligence, elegance, and aplomb. Following and elaborating upon the work of the woefully and absurdly underappreciated historian Constance Rourke (1885-1941), who in 1931 identified four quadrants of “American humor,” Murray envisioned the mainstream of American identity as composed of four tributary streams: African American (he preferred the terms “colored” or “Negro”), Yankee, Native American, and Frontiersman. Murray used this to reconceptualize American (and thus African American) identity as the literal vanguard identity of modernity, not one lagging behind modernity, for better or worse. That’s a synopsis of what gets explained, as you know, in rich and dynamic essays. Murray’s conception of African American identity is parallel in many ways with (in fact, it’s almost exactly the same as) Édouard Glissant’s later theorization of Caribbean identity: a new cultural formation that is hybrid, flexible, informed by various complex sources, and not directly descended from Africa — having to do with relations between people, customs, cultures, ideas — not in any way a straight line of descent — and reflective of actual life in the Caribbean, rather than a theory conceived by a myopic academic. I don’t know if Glissant was influenced by Murray. I’m bringing up Glissant to illustrate that it’s not an American nationalistic thing. It’s a thoughtful observation informed by vast knowledge of texts and human relationships. Look at the last paragraph here for a fine application of Glissant’s thought. Murray and Glissant both see the Middle Passage as a dividing line, after which new cultures and identities emerge in the Western Hemisphere. This statement comes at the beginning of Murray’s The Omni-Americans and at the beginning of Glissant’s Poetics of Relation. Murray applies Thomas Mann’s insight about the depth of “the well of the past” — explained by the narrator at the opening of Joseph and his Brothers — to the African American experience. The narrator says (so much more poetically than the way I’m about to paraphrase it) that the well of the past is bottomless, it recedes forever, but stories have to start somewhere. So, Murray chooses the Middle Passage. But it can also apply to a steerage passenger in 1895 or an immigrant on a plane in 1970 or someone making a mad dash across the border in the 2000s. I am not comparing those journeys to the horrors of the Middle Passage, but simply saying that they demarcate new cultural beginnings. And — and this is critically important — upon entering the United States, one partakes, in one’s new cultural environment, in what has developed out of the new cultural beginning that began with the thousands of Middle Passages. Murray then combined Rourke’s insight with Paul Valéry’s insight (1922) that “the European” identity is a combination of Greek, Roman, and Jewish heritage. It may be other things too, but for Valéry, that combination is what distinguishes it from other regional identities. Of course, those traditions had myriad influences at work in them as well. There was an interesting book a few years ago called Babylon, Memphis, Persepolis: Eastern Contexts of Greek Culture by Walter Burkert (Harvard UP, 2004). There are plenty of “pre-Greek” things in Ancient Greek culture as well — residual archaic things, influences from the north and the south, as well as elements from the broad current of proto Indo-European culture. But that’s not the point. The point is new identities form organically out of a variety of combinations. American identity, for Murray, first took shape from the 1600s through the early 1800s. Other groups came and augmented it. Any group that comes here can and often does augment the base. It’s not a rigid conception. I’ll share a brief vignette, which I’ve gotten a few laughs from at panels and such. Parsing this could keep people busy for the next few decades. Haha. Murray is not the first person to point out that race is a construction or that whiteness is an ever-expanding blob or whatever, but his own take on it was something else:

Murray: What kind of Irish are you?

Me: Huh?

Murray: You know, New York Irish, Boston Irish . . .

Me: Oh. Well, my dad came here from Northern Ireland and my mom’s family is New York Irish. Her father was from Boston, but moved to New York in 1941.

Murray: So you know about the Boston Irish?

Me: I mean, a little, but not really.

Murray: You know why they’re mad?

Me: They’re mad?

Murray: They’re mad at Negroes, man!

Me: Oh yeah, I guess I’ve read about that. James Brown at the Boston Garden and such. Why are they mad?

Murray: Because they can’t afford to hire Negroes to teach them how to be white! (big laugh)

Murray loved jokes like that — and he had a few more. The point is that identities are complicated constructions and the attempt to construct a pure one is absurd. He said in an interview in the 90s that of course Negroes know that whiteness is a myth — we helped invent it! It was black women who were slaves, he said, who created the glamour of the white southern belle. Here’s an addendum to that: how many affluent white golfers have learned the fine points of the game from black caddies? (A lot!) Murray said at the Alain Locke Symposium at Harvard in 1973 (organized by Lewis Jones, by the way) that he recoils from the idea of a pure identity. Murray’s conception of a flexible Omni-American identity is ultimately (and perhaps the ultimate) anti-authoritarian and anti-fascist conception, in part because it undermines and repudiates the possibility of there having been a golden age or mist-cloaked time of purity, on which those conceptions rest. The Omni-American concept is not unrelated to the mestizaje concept about Mexican culture. It has worldwide applicability. It requires a deep breath, a step back, and an honest assessment. Of course, its roots go back to Frederick Douglass, in works such as “Our Composite Nationality” (his 1869 defense of Chinese immigration) and there are cognates in the early work of Du Bois. Ellison articulated something similar, but in a more diffused way. Murray nailed it and put his own spin on it.

What was the reaction to Murray’s theory of America as a “mulatto culture”?

Very positive! Many people have described The Omni-Americans as a breath of fresh air when it appeared in the spring of 1970. It was irreverent, learned, funny, and accessible. What a combination! But that was Murray. That was his personality: hilarious and erudite. It got enthusiastic reviews, including a long one in The New Yorker, by Robert Coles. It was a Book-of-the-Month Club alternate selection. Murray went on the David Frost Show. He also appeared on the cover of Book World, the Sunday book review section that was a joint venture between the Washington Post and Chicago Tribune. Writers as different from one another as Larry Neal, Walker Percy, Alfred Kazin, and Skip Gates all admired it. It caused Horace Kallen, who was nearly 90 years old, to take notice and adjust his views of American culture! Ain’t that something? The worst review it got was by J. Saunders Redding in the New York Times — but that was the outlier. Redding and Ellison had been feuding in dueling book reviews since about 1950, so it’s no surprise that he took a shot at Murray. But Redding’s review had little influence. The book was reprinted in paperback the next year, and there were subsequent editions in 1983 and 1990, printings of which continued through the early 2000s. Redding must have felt bad by the mid-1970s, because he tried to get Murray a job at the Library of Congress (but Murray didn’t need a job and wasn’t interested).

Now, there’s a phrase Murray likes to use, and others, too, that not everyone might be too knowledgeable about. That phrase is “the blues idiom statement.” You and I know it to be a crucial aspect of his views on culture and art, but could you talk a little bit about how we can reconcile the blues idiom statement with Murray’s theory about the Omni-American?

There is no contradiction between Murray’s celebration of African American cultural achievement and the Omni-American concept, because for Murray, the black contribution is, in general, what is most American about American culture. Murray emphasized the importance of the idiomatic and the cosmopolitan. Along the same lines, he also emphasized an apparent paradox: the more idiomatic a work of art is, the more universal its applicability and reception. He looked to James Joyce as a model — a cosmopolitan who was exceptionally idiomatic, and who made his idiom feel universal. Another writer like that, I think, is Mahasweta Devi: her writing is very idiomatic, yet you get it. Murray said one difference between him and Ellison is that Ellison explains a lot of black stuff for white folks, which he (Murray), refuses to do. But Joyce and Devi don’t explain either. See what I mean? He wanted to be the most universal writer by being the “blackest” writer, just as he found other writers who plunged into their own idioms to be the most universal. He said in a 1994 interview:

My work doesn’t ever stick to ethnicity and yet I don’t want anyone to ever be thought of as a greater authority on ethnicity. They should say, ‘Ask him, he knows.’ Or, ‘He’s got the voice. He’s got the this, he’s got the that.’ . . . I want to say that Negroes never looked or sounded better than in Murray and Duke.

Yet ethnicity resides in the idiomatic. I’ll get to that. He felt that his work and Ellington’s work reflected the Omni-American ideal — but not any more so than Hemingway’s work! I’m looking forward to more people getting a chance to read his sixty-page essay on Hemingway as the exemplar of the blues writer, especially the rollicking second half of it, in the Library of America edition.

So how did Murray understand the idiomatic per se?

Murray went so far as to redefine race in terms of idiom — he sought to redefine ethnic difference as idiomatic difference. In a late notebook entry he wrote “My so-called blackness should be considered as a matter of idiomatic variation (nuance and sample), much the same as is William Faulkner’s southernness, or Fitzgerald’s mid-western Ivy Leagueness or Hemingway’s mid-western internationalism.” This is remarkable. Every group has an idiom of some kind, from broadly defined ethnic groups in general, down to combinations of a few individuals: families, couples, siblings. Idioms develop in physical proximity and they are diverse, flexible, and divisible. Definition number one in the Oxford English Dictionary defines “idiom” as “the specific character or individuality of a language; the manner of expression considered natural to or distinctive of a language; a language’s distinctive phraseology. Now rare.” But not rare in Murray’s work! Murray had a wonderful Yogi Berra-esque phrase to quickly describe the idiomatic: “mispronouncing the words correctly.” (!)

Idiom, by the way, always implies community and is the product of an exchange between others. If an individual has a quirky, personal way of speaking, then, that’s an idiolect, not an idiom. Now, an idiom is not an accent, but an accent is part of an idiom. Hurston notes the difference between writing in idiom and writing in dialect in her essay “Art and Such” (1938). So, Tony Soprano speaks in a blue collar Northern New Jersey Italian immigrant-derived idiom. Other characters on that show speak in other idioms — such as the doctor who lives next door to Tony, for instance. Paul Volcker speaks in another New Jersey idiom. I like how Volcker talks. People don’t talk like that anymore. Volcker’s idiom is not the old WASP idiom, which also survives in a few places yet and is also pleasant to listen to. I think most old, long-simmering idioms have a musicality to them. Class figures into this as well. The people of the Gold Coast of Long Island knew the idiom of their servants and the servants knew their idiom in return. Servants could speak in the idiom of their employers on the job and then switch back to idioms they were more comfortable with when off the clock. When this gets into masks and parodies and parodies of parodies, things can get interesting. Physical proximity and idiom are also connected. Slavery and later segregation enforced physical proximity, which helped lead to the development of the blues idiom — a term coined by Murray — which is a particularly enduring idiom (partially because of continued, de facto segregation). And yet physical proximity also meant various forms of cultural sharing, borrowing, and theft. The blues idiom is the southern, working class African American idiom, very broadly defined. Music and painting and clothing and anything people create is in an idiom of some kind. Humanity itself is an idiom of sorts. When Wallace Stevens writes of “the idiom of the innocent earth” he is highlighting the difference between the human and non-human. Every idiom has subsets and there is diversity within any idiom. There is overlap between idioms and one person can be an authentic speaker of several. Murray was once asked why he lived in Harlem even though he could have afforded to live elsewhere. He said he (and Ralph Ellison) didn’t want to be too far away from the idiom. Harlem has varied idioms, and different idioms there have been influencing one another for the past hundred years, but Murray meant, more or less, the southern African American idiom. As I said, to say idiom implies community, being with others. If we had another fifty thousand words I’d bring the work of Emmanuel Levinas and Jean-Luc Nancy into the discussion. Haha. Now, I’ll bring this to the “blues idiom statement” in music. When Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn were re-composing Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite in the late 1950s, there was a point where Strayhorn left something in the score exactly as Tchaikovsky wrote it. Ellington asked him “why is that like that?” Strayhorn said, “well, I didn’t want to alter the great man’s choice in that particular section.” Ellington said “no, that’s not right for my band.” In other words, he was telling Strayhorn to restate it in the blues idiom (as they were doing for the entire composition). Murray was there, in the studio, and witnessed the exchange. He liked to tell that story. It’s in the “Tuskegee” chapter of South to a Very Old Place as well, so much better than I’ve paraphrased it here.

That’s beautiful. The “observer,” whether it’s Murray witnessing the exchange between Ellington and Strayhorn, or a third line apprentice musician trying to learn the blues idiom, plays quite the role in disseminating both history and culture. One of the more controversial episodes of Murray’s career occurred upon publication of Stomping the Blues when he referred, in a photo caption, to a group of white musicians as members of the third line behind Harlem schoolchildren who were following Count Basie. Many white jazz writers who had a bone to pick with Murray read that caption, seized upon it, and said “Murray doesn’t like white musicians.”

That’s what they said, in the cheapest and laziest readings they could muster. That’s why Murray wrote a short essay explaining himself (“Notes on a Jazz Tradition”), which appears for the first time in Murray Talks Music. I recently interviewed Harris Lewine, the art director of Stomping the Blues. Lewine told me he specified character counts for each caption, and that Murray wrote those captions to fit the specified counts exactly. So, perhaps with an extra few sentences in 1976 Murray could have cleared it all up. Still, the controversy didn’t seem to bother him much until 2003, which is when he began to work on the explanatory piece. He wasn’t too interested in the opinions of some white jazz critics in the 80s and 90s who felt Jazz at Lincoln Center was too black. By the way, John Gennari defends Murray on that point in his comprehensive history of jazz criticism, Blowin’ Hot and Cool (U of Chicago P, 2006). In my introductory note to “Notes on a Jazz Tradition” I explain the controversy and quote Gennari on Murray’s critics. Murray’s point, in short, is as follows (and this is my paraphrase): first line/second line/third line doesn’t mean first best/second best/third best. It identifies physical position in the traditional New Orleans parade and is not a value judgment. Those closest to the idiom by having been born into it comprise the first line of musicians and second line of dancers, while the third line is comprised of those who are admiring and observing the idiom in order to learn about it. (Perhaps people know more about this today from second line videos on social media than they did in the past.) In the original version of Murray’s essay on James Baldwin (which appeared in 1966 in the book Anger, and Beyond), he has, as an aside, the following quote, of exceptional clarity, which did not make it into the expanded version published in The Omni-Americans:

This music [jazz], far from being simply Afro-American (whatever that is, the continent of Africa being as vast and varied as it is), is, like the U.S. Negro himself, All-American. This is why so many other American musicians, like Paul Whiteman, George Gershwin, Benny Goodman, Woody Herman, Gerry Mulligan and all the rest, identify with it so eagerly. The white American musician (excluding hillbillies, of course) sounds most American when he sounds most like an American Negro. Otherwise he sounds like a European.

The reason African American musicians, in Murray’s opinion, tended to play blues and jazz more idiomatically than white musicians was because they tended to have a larger idiomatic musical vocabulary from their exposure to and/or involvement with the black church. You remember the line in Murray Talks Music about the difference between Gershwin and Aaron Copland? Gershwin was hanging out on 135th Street, where he was absorbing the idiom in a studious and non-frivolous way — not just music, but the way people talked, walked, and so on. It’s all connected. Copland wrote marvelous music on American themes — it’s just not in the new form that developed here. Copland is my go-to music for grading papers, along with Virgil Thomson.

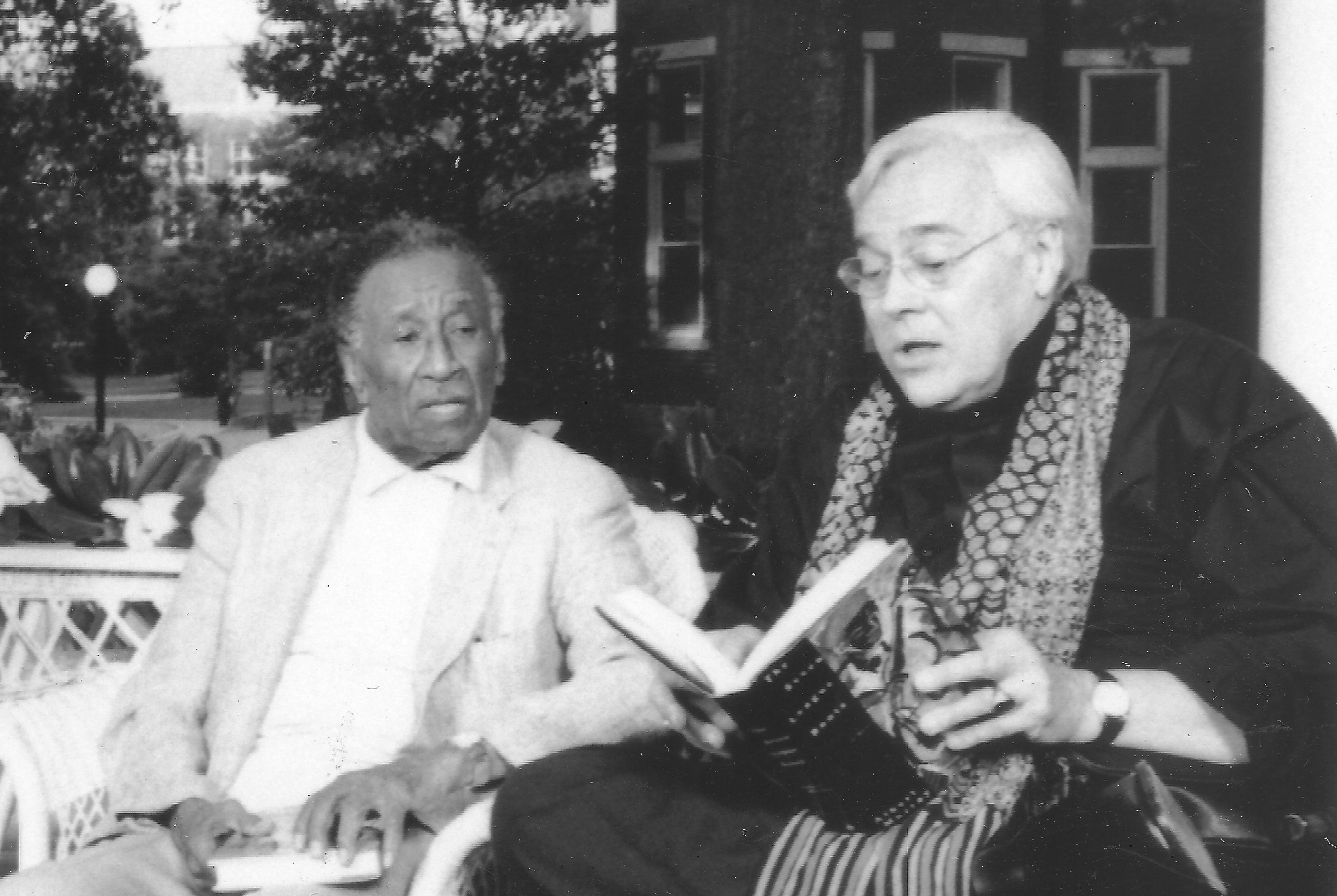

Let’s talk about that essay on Baldwin and the sections pertaining to Baldwin in particular. I’ve been curious about that, as well as about Murray’s essay on Gordon Parks, both in The Omni-Americans. Murray presents harsh critiques of two of his friends. Yet Parks and Baldwin both seemed to forgive him for it or at least seemed not hold it against him. I’ve seen the late 1970s clip of Murray in conversation with Baldwin, Bearden, and Alvin Ailey (and the transcript in Conversations with Albert Murray). I’ve also seen photos of Parks and Murray in what seems to be the 80s or 90s. You recently reviewed the catalog to the new exhibition on the Ellison-Parks collaboration. How well did Murray know Parks, and how was it different from Ellison’s friendship with Parks? How well did Murray know Baldwin? How did they feel about his criticism?

I haven’t read the private papers of Parks or Baldwin, so I don’t really know, but you’re right: they didn’t seem to have held it against Murray in the long run. And why? The essays pull no punches, but if they are harsh, they are harsh in a corrective sense: harsh in the sense of Murray wanting Baldwin and Parks to be the best they could be. Murray felt that each man had profound insight and talent, and each man’s story reflected an achievement for black Americans, yet a reader wouldn’t get the sense from their work (he was critiquing Parks’s books, not his photography) that the worlds they grew up in could produce artists as great as they were. In other words, their writing, in Murray’s opinion, didn’t live up to the dynamism of their personalities or reflect the possibility inherent in their personal stories and thus, at the same time, they were giving short shrift to the dynamism of black communities. Murray often talked about how it is difficult for a novelist to create a protagonist as smart as he or she is. Parks has an incredible story, yet Murray argues that his novel and memoir to this point don’t portray the world of possibility in which the dashing, debonair, and brilliant Parks could have developed. Murray argues that you wouldn’t know from Baldwin’s depictions of Harlem life that a writer and conversationalist as talented as Baldwin could have emerged from that same Harlem. Such depictions are something Murray sought to counter-state by portraying these communities from different angles in his own fiction. Incidentally, Murray was pleased when John Leonard, in Harper’s, noticed this and called his 2005 novel The Magic Keys “a thank-you note to the entire sustaining community of black America” (among other nice things).

Murray was something like a mentor to Baldwin in Paris in 1950. (Murray was eight years older.) There’s a 1951 letter from Baldwin to Murray, expressing the wish that Murray was still in Paris. So I mean, there was a deep personal connection there prior to Murray’s essay, which first appeared in 1966, and which appeared again, in an expanded version, in The Omni-Americans in 1970. I think Baldwin knew him too well and admired him too much to hold it against him.

And Parks?

There isn’t as much of a paper trail about his friendship with Parks. He could have met him in 1947, through Ellison, or he could have met him in the late 50s, through Ellington. Murray was spending a lot of time in 1947-48 hanging out with Ellison and Ellison was collaborating with Parks on the photo-and-text series that is now part of the exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. Parks stayed at Ellison’s place now and then and Murray went to parties at Ellison’s — in short, they could have crossed paths. But you’re right, there are several photos of Murray and Parks from the 80s and 90s. Michael James told me about a party he and Murray went to at Parks’s apartment in the late 90s. My hunch is that Baldwin and Parks either saw some legitimate points in Murray’s critiques and/or that they knew Murray had constructive intentions. Incidentally, in Murray’s third novel, The Seven League Boots, he includes a charming and affectionate portrait of a very Baldwin-esque writer, whom the semi-autobiographical protagonist, Scooter, meets in Paris.

Murray had deep admiration for French culture and the French language. Let’s talk about his 1950s lectures in Morocco, delivered in French while he was serving in the Air Force, which were also his first public statements on jazz. Murray says in one of those lectures that jazz demonstrates “the necessity of continuous creation in a perpetually oppressive and unstable world.” By the time this talk appears in the book, we’re used to Murray referring to jazz as something that is both idiomatically American and universal. The series of talks he gave in 1956 and 1958 were well-attended. Do you think jazz is the first American expression or product to go global? How does it figure into America’s postwar influence?

Jazz is not the first American cultural creation to go global — look at Whitman, Poe, and Emerson. Jazz reached global audiences by the 1920s, but was used as propaganda by the U.S. State Department from the mid-1950s through the 70s. There have been several books about this — the big one is Satchmo Blows Up the World by Penny von Eschen (Harvard UP, 2004). I recently published a peer-reviewed article, “Jazz Autobiography and the Cold War,” on the way that the influence of the Cold War seems to have shaped key texts in the tradition of jazz autobiography. Those propaganda tours had a whirlwind of complex motives behind them, but they were not all bad all the time: a lot of people behind the Iron Curtain and in the so-called third world got to hear a lot of great live music and plenty of jazz musicians got paid well. For musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie, the tours helped to offset the prohibitive costs of running a big band. And of course, many musicians got to hear a lot more sounds than they would have heard otherwise. Who knows, perhaps Ellington’s Far East Suite and Latin American Suite may not have been composed if he had not jammed with local musicians in places like Baghdad and Montevideo. Overall, the tours were, as people like to say, “problematic,” but just about everyone involved was well aware of that from the get go. It all got going shortly after Gillespie gave an impromptu concert in Greece, which helped to calm student unrest in spring 1956. It wasn’t part of a coherent, subtle, clandestine strategy, like the C.I.A.’s well-documented support for literature (or support for literary journals in order to provide cover for operatives) — the jazz/propaganda machine was thoroughly improvised, and full of contradictions. Following Gillespie’s concert in Greece, the State Department soon launched a massive program featuring Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, Dave Brubeck, and many others. By 1962, Brubeck and his wife, Iola satirized these propaganda tours in their musical The Real Ambassadors, which starred Louis Armstrong (and which features some beautiful, non-satirical songs), who nevertheless made an album called Ambassador Satch.

Murray’s early lectures in Morocco, delivered in French and sponsored by the U.S. Information Service, preceded Gillespie’s 1956 concert by a few months. Murray doesn’t seem to have done any in 1957. They picked up again in 1958. Maybe he did a half dozen altogether. It’s kind of funny, and also kind of cool that his first public statement on jazz — his first public nonfiction statement in general — was in French, when he always emphasized jazz as a cultural contribution of the United States. Murray’s lectures may have been the very first official attempt to use jazz for diplomacy. Their specific goal was to improve relations between the U.S. Air Force and the locals. Flyers for the lectures were printed in French and Arabic. Incidentally, despite the success of Murray’s well-attended lectures — he received enthusiastic letters of commendation from American diplomats and superior officers, including a general — they did not help his Air Force career or his writing career at all. He probably should have been sent to lecture around the world. He was an enthralling speaker! But he also didn’t have a book out yet — another long story. Imagine a scenario in which he’d been sent to lecture all around North Africa and the Middle East, drawing bigger crowds all the time. Who knows — maybe history would have turned out differently.

As we gather from the conversations collected in Murray Talks Music, we know Murray could really tell a story and communicate. He could improvise in conversation like it was nothing. There’s this great conversation between Loren Schoenberg, Stanley Crouch and Murray that was recorded on a WKCR radio show in New York and which you’ve published for the first time. It’s an enormously rich conversation, and one truly receives an understanding of who Murray was, what his humor was like, and how he interacted with colleagues who were decades his junior. What’s the wider significance this interview holds for the study of Ellingtonia?

Aside from containing a treasure trove of information and a variety of valuable perspectives on different moments in Ellington’s career, as well as intriguing glosses on specific works, it models the level of rigor that must be brought to study of his life and work. It features three world-champion quick wits and unparalleled Ellington experts, so it’s really special. It’s like the combination, in the old west, of being fast on the draw and having aim. I’m grateful that Loren and Stanley gave their permissions for the conversation to be included in the book. Stanley recently won the Windham-Campbell Award, by the way, and it is well-deserved. Profound scholarship and depth was and has long been out there in Ellington studies, in the work of Mark Tucker, Harvey Cohen, Maurice Peress, and many others. Ellington’s work, like that of Ralph Ellison, Wallace Stevens, and plenty of others, attracts top scholars. But hacks, like the blues, will always be back, and so, vigilance in defense of reputations — especially those of black artists, especially when it looks like fair play and historical accuracy has gone out the window in the interest of demoting their reputations — is always needed. Hacks often try to exert downward pressure on the reputations of the great: look at the recent backlash against Joan Didion. Soon — bet on it — there will be an essay called “Hear Me Out — Maybe Marilynne Robinson Isn’t That Good? [Ducks]” on some literary website. You’ll be pitched it in the near future. Haha. Watch. People will gasp and get mad and debate it, and so on. The same people who liked to play hall monitor in grade school often like to do the same thing on the literary-cultural internet. But I suppose it is not just a feature of the internet: Delmore Schwartz published an attempted takedown of Hemingway in Southern Review in 1938. Then there was James Baldwin’s essay on Richard Wright. There are many other examples. But the click economy, and the need to drum up outrage and debate on a daily basis, leads to more of that kind of thing. Yet it’s slightly different with Ellington: there has been an effort to undermine him ongoing since the 1940s. The anti-Ellington stuff a few years ago was disconcerting, as I describe in my introduction, but it was a rehash of a similar thing in 1987. And the fact that they keep trying is a testament to his achievement. Imagine the amount of bullshit he had to endure in order to see his grand artistic vision come to life over six decades? That’s the story, a heroic story, that an editor should want to sign up.

Why are Ellington and Armstrong so important to Murray? Are they deserving of being considered the best American artists?

I’d say Armstrong and Ellington are among the most important artists in all of human history. I don’t think they need any qualifiers. To qualify their achievements would be like saying Tiepolo was one of the best painters of his day, in Italy, or later Spain, where he moved for commissions. Take a look at Roberto Calasso’s book Tiepolo Pink (2011). Or, it would be like saying “Michelangelo was a really good sculptor — for the first half of the sixteenth century, at least.” It doesn’t sound right. Don’t get me wrong: critics and scholars should use their knowledge and judgment to make fine distinctions and qualifications, but a few artists are just beyond all that. Armstrong and Ellington are among the few artists to whom “of all time” can fairly be appended. Murray liked to say that Armstrong’s and Ellington’s contributions to the language of jazz were analogous, respectively, to the contributions of Chaucer and Shakespeare to English literature. Incidentally, I don’t think that Chaucer, with his court sinecures and whatnot, was much like Armstrong in real life, but Ellington’s real similarities with Shakespeare are myriad and uncanny. Yet Ellington’s music in a sense comprises a vaster universe than Shakespeare’s plays (which inspired Ellington and Strayhorn’s Such Sweet Thunder). Jo Jones was right when he said (in Rifftide) that it could take 200 years to fully appreciate Ellington’s music and that we haven’t even gotten to the surface yet! When he said that, in the 1970s, most of Ellington’s scores — the sheet music for hundreds or probably thousands of pieces — were unavailable. Todd Stoll, of Jazz at Lincoln Center, recently told me how Jazz at Lincoln Center led the effort to make these scores available, and has donated 200,000 copies to high school music programs. Incidentally, the opinion of someone like Jo Jones on Ellington should be taken as seriously as Mozart’s opinion of Handel.

When we consider the significance of these musicians, whose music composes the very soul of this nation, we really need to re-train our ears to hear just how revolutionary their sound was. I mean, the synthesis, the originality, the swing; it’s unprecedented in human history.

Maybe some people need to re-train their ears and some people don’t, depending on the breadth of their musical exposure and education (formal or informal). Sometimes listening to jazz, for someone raised entirely on later music, requires an adjustment, or listening from another angle maybe. The rise of the backbeat in popular music kind of parallels the rise of the automobile, especially after World War II. Rock and rap sound really good in moving cars. In the 1991 comedy King Ralph, in which John Goodman plays an American slob who inherits the British throne, his character notes that in the doo wop song “Duke of Earl,” the “Duke, Duke, Duke” plays in tandem with a car passing lane dividers on the highway at 55 miles per hour. Incidentally, the tune was sampled by Cypress Hill around that time. There should be a book on the doo wop roots of hip hop, in which the preceding example would only be a footnote. An example can be made with that tune’s lyrics, but it’s really about the backbeat, which is aurally addictive and attractive, seeming to fit with contemporary motion and affect. In the 1960s and 70s Ellington experimented with the backbeat as well. I like both beats. So does Christian McBride — one of the great musicians of our time.

Big bands got to swinging the blues idiom statement in the 1920s and kept it up for a few decades afterwards. What was the inspiration for the fully orchestrated blues idiom statement? How did the sound that originated in the South become the soundtrack to life in northern urban centers?

I don’t know if the geographical divide means too much here. These things are mysterious. Nobody played the blues better than or had more natural feeling for it than Johnny Hodges, who was from Cambridge, Massachusetts. I’ve heard a certain jazz paradox pointed out many times over the years, (and I’m forgetting where I picked it up from), but many would agree that Hodges had an easier knack for playing the blues than say, Coleman Hawkins, who was from Missouri, where perhaps you’d expect a musician to have a closer relationship to the blues. It’s a good old American paradox. The fully orchestrated blues idiom statement — say, a big band jazz arrangement done right, as Ellington and Strayhorn and many others did hundreds if not thousands of times, is often an onomatopoeic impression of a train: the rhythm section approximates the wheels and the train’s whistles are heard in the brass and wind instruments. A lot of people don’t realize that. Murray spells all this out in Stomping the Blues as nobody had come close to before, but there is plenty of evidence going back at least to the 1930s that this is how artists such as Ellington and Basie were conceptualizing their music. Take a look at this early 1930s clip of Ellington at 1:16:31 in the outstanding documentary Bluesland (which features Murray and blues scholar Robert Palmer as commentators). Before reading Murray I already had an idea about locomotive onomatopoeia through “The JB’s Monaurail,” which I learned about through EPMD’s “Let the Funk Flow.” As good as “The JB’s Monaurail” is, it is kind of simple compared to Ellington’s explorations (which are diverse, reflecting many different types of trains, yet are only one aspect of his enormous oeuvre). There were several levels of train imagery in African American culture during Murray’s youth in the 1920s and beyond: the metaphorical freedom train (the Underground Railroad), the metaphysical gospel train (to Heaven), the train as communication network, as the porters transmitted news between black communities, and the actual train as a method of transportation out of the south and/or within the south and elsewhere, and not always for a fee, if you could “catch an armful” of it (as Ellison did to get from Oklahoma City to Tuskegee for the first time). For some good books with different perspectives on this, take a look at Kevin Young’s essay collection The Grey Album and Joel Dinerstein’s study Swinging the Machine.

This is the second book about jazz that you’ve edited. What is your background within the genre?

Studying on my own is part of what led me to Murray, but my education in jazz mostly comes through Murray and Michael James (1942-2007), who was Ruth Ellington’s son and Duke Ellington’s nephew, and was a jazz historian and a thoroughly informed “underground” intellectual of the sort who once populated Manhattan. Through Duke, he was also like a nephew to Murray, and Murray put me in touch with him in early 2002. Mike was famous for his late-night phone calls. If you wanted to learn about say, the genealogy of the trumpet from Roy Eldridge through Freddie Hubbard from 1am-2am on a Tuesday morning, Mike could oblige. Or, he would call you at that time to tell you about it, even if that topic was not of pressing concern to you at that moment. Haha. He could also tell you what it was like to hang out with Cootie Williams on tour in the late 50s, or what it was like watching Teo Macero in the studio. Unfortunately, he never wrote anything down. He could have been anything he wanted — a writer, a professor, anything — but he was a man of leisure. Perhaps he was like a learned English country squire — but the native New Yorker version. He was kind of a melancholy guy in that he had a longing for the lost jazz world he grew up in. But he also had a good, idiosyncratic sense of humor and a wry perspective on current events. He’d say “we’re living in Balzac’s Paris, Paul!” That was say, 2005. Imagine what he’d think now! I learned so much from him about Ellington, and also about Roy Eldridge, Coleman Hawkins, Paul Gonsalves, Jo Jones, and so many others. But he had comprehensive knowledge about other topics too, especially American history and literature. Mike introduced me to Clark Terry, a mentor (his childhood trumpet teacher, until health precluded Mike from continuing) and lifelong friend, and almost got me a job driving for him. Mr. Terry ended up hiring one of his own former students, so that made more sense. Still, I’m grateful for having chatted with him a few times, in our interview and elsewhere. Anyway, I tried to make my jazz collection mirror Mike’s and Murray’s. And I read the jazz books they pointed me to. But I’ve studied a lot on my own. I did an enormous amount of background research for Rifftide. I learned a lot from talking with master drummer Michael Carvin. I’ve had extensive and fascinating conversations over the years with all sorts of musicians and critics. My academic specialization is in twentieth century American literature, particularly African American literature (and I also have expertise in nineteenth century American literature), but I admire the old eclectic New York intellectual tradition of knowing a lot about a lot: film, painting, sports, politics, history, business. You never know who knows what, and no credential can really tell you once and for all, and so you have to listen, and not assume.

You came up in the rap era, so did you have to retrain your ears to get into jazz?

In general, I suppose I first got into jazz and other earlier music through rap samples. Yet I was always somehow vaguely attracted to the big band sound — through old movies, or newer movies about World War II, I guess. I was too young to know anything about the big band revival in the 80s. But I was conscious of Tony Bennett’s comeback in the early 90s and I somehow appreciated it on some level. When I really started listening to jazz, it was not Ellington and Armstrong, but late Coltrane. I liked Pat Metheny too, and Bob James. I’m talking about when I was in high school, circa 1997. Simultaneously, I was really into James Brown and the JBs. I’d go to see Maceo Parker. I tried to check out works sampled by the producers I liked: Pete Rock, RZA, DJ Premier, KRS. Pete Rock gave an interview in the early 90s and admonished young people to check out old music. I kind of took that to heart, as I was going in that direction anyway. This was what they called the crate-digging era — producers were hunting for samples in old music. Anyway, I got into Ellington and Armstrong and Basie around the time I started reading Ellison and Murray, and it all clicked with me instantly. It was what I had been looking for. To your point, I don’t think Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie (and Benny Carter and Jimmy Lunceford and Mary Lou Williams) do not or should require a “retraining” of late Gen X or Millennial ears. But I suppose, as I said above, it depends on the background of the individual. And knowing where to start is important. I’d advise a kid today, if starting from scratch, to start with stuff made in modern studios (such as Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy or Satch Plays Fats or Ellington from the late 30s on), so they’d have an idea of what it perhaps sounded like in the 20s and early 30s, when the recording technology was not as good, when the bass could not be heard as well, and so on. Then, approach the earlier stuff. Up-tempo blues and swing is my thing. I’d suggest starting with something that swings hard, so that you understand what it is right way — the 1950s “Kinda Dukish/Rockin in Rhythm” medley with Quentin “Butter” Jackson’s trombone solo (at 3:48). I’ll give a few examples for someone who has had no exposure to this cosmos of music. The following is not even a cursory list, never mind comprehensive or definitive. Listen to Basie’s entire 1936-46 catalog. Basie’s “Every Tub” (1938) seems to contain the compressed future of the next fifty years of American music (from r&b to heavy metal), especially in the last minute. Check out Basie’s “The King,” or “Doggin’ Around,” or his signature numbers such as “One O’Clock Jump,” or his version of “Five O’Clock Whistle” (especially after the two-minute mark). Check out Ellington’s “Ko-Ko” from the 1950s Historically Ellington album (n.b., some knowledgeable people think it’s not as good as the original, but I just prefer to listen to it), “Body and Soul” from the album Duke Ellington’s Spacemen, and of course, the miraculous “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” from Newport in 1956. Knowing where to look is crucial. On the other hand, take McKinney’s “Cotton Pickers,” a top dance band of the late 20s and early 30s. I know it’s good and influential, but I can’t get into it. When I listen to it I continually reimagine what it could have sounded like a few years later, after Basie’s swing revolution. Now, that’s not the case with an immortal Armstrong piece from the 1920s, such as “King of the Zulus” or “Weatherbird” — either of which I could listen to over and over. I don’t think I’d tell a kid to start with “Potato Head Blues” or “West End Blues,” sublimity and canonicity notwithstanding. “King of the Zulus” seems underappreciated and underdiscussed to me. (I typed this before I knew that my acquaintance Ricky Riccardi, a top Armstrong scholar, led a band that did this tremendous cover). On the other hand, I love James Reese Europe’s music, which predates that by a decade. “Down Home Rag,” a hit of the 1910s, which jazz musicians stopped covering for some reason around 1940, is something I can listen to all day, and I’m always on the lookout for covers of it. (It was recorded widely from the 1910s through the 1930s.) I listen to “Down Home Rag” in the car. I also listen to Ellington from the 20s to 70s, along with Basie, Benny Carter, Mary Lou Williams, Oscar Peterson, Clark Terry, Mingus, and contemporary artists such as Ethan Iverson, Jaimeo Brown, David Murray, Aaron Diehl, Wycliffe Gordon, Vijay Iyer, Brandee Younger, and so on. But I also listen to Laura Nyro, 19th century Irish street songs, 17th century English songs like “Hey Ho to the Greenwood,” and Gilbert and Sullivan songs — among a zillion other things. I never had any formal or self-conscious “retraining.” Perhaps it’s a long process. Let’s compare this with old movies. I love to show students movies from the 30s through the 50s. Most have never seen anything from that period, but they’re fascinated and sometimes enthralled when they do (even though some express skepticism at first), because in general, it was a better era of movie making. It takes no retraining of the eyes. It only takes knowing what’s out there and where to look, along with some contextualization. All it takes is a conceptual leap beyond what’s forced on the consumer.

I want to address Richard Brody’s criticism of Murray that appeared on The New Yorker’s website under the headline “Albert Murray and the Limits of Critics with Theories,” which was tweeted to millions with the headline “Beware Critics with Theories.” The title is misleading, I think, because Brody goes on to say that Murray was not a critic. Did Murray wish to be perceived as a jazz critic? Was he opposed to avant-garde jazz of the late 60s and early 70s?

This is a long and complicated story, with a backstory. There is an idea out there, trotted out more than one might think, that Murray and Ellison didn’t like bebop. In a sense, it’s kind of a testimony to the power of their ideas that people get mad that they (think they) didn’t like something. Murray did in fact like bop — exponentially more than Ellison did — and Murray Talks Music makes that abundantly clear, in the Gillespie interview, in Appendix A (Murray’s canon of jazz arrangements), and elsewhere. Murray Talks Music highlights his appreciation of bop, but it was never a mystery and never possible for a truly attentive reader to think otherwise.

Richard Brody is a smart and idiosyncratic critic, but paradoxically, for such a independent thinker, his critique of Murray kind of comes off like the mad-libs version — fill in the template. Yet he also compared him to Barthes and Bazin, which is cool. I follow Richard’s work and often enjoy it. I don’t always agree with him, but he’s thoughtful. He wrote an excellent review of the 2014 exhibition of Ralph Ellison’s record collection, for which I was a curator and literary consultant, at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem. Brody was the only critic of his stature who paid any attention to the exhibition. I’m grateful for his interest and review. A week later he reviewed a documentary featuring Ellison called “Jazz: The Experimenters,” which Ellison pushed to get produced by National Educational Television and which aired in New York City and environs in 1965. Brody was once again one of the only critics to pay it any mind, but I think his review missed the big picture. I’ll explain. I unearthed this documentary, which as far as I could tell was last screened in 1995 at the Library of Congress. I hosted a screening of it (and other films featuring Ellison) at Maysles Cinema in Harlem in March 2014 as part of the Jazz Museum’s celebration of Ellison’s centennial. It was tied in with the exhibition. Brody did not attend the event at Maysles. He went to the Jazz Museum and watched it privately, so he didn’t hear my contextualizing introduction. Ellison was on the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television, which advocated the creation of public television system in the United States, and issued a book-length report on its findings (published as a mass-market paperback!). Ellison was one of the most high-profile/high-prestige advocates for public television and probably (along with James B. Conant) the most famous person on the Commission, which included several university presidents, leaders of industry, a concert pianist, a diplomat, and a labor leader. So, in the spirit of jump-starting public television, Ellison becomes the driving force behind one of the earliest public television documentaries, “Jazz: The Experimenters,” featuring the Cecil Taylor Quartet, and the Charles Mingus Ensemble, performing at the Village Gate. Ellison and the jazz scholar Martin Williams provided commentary. Ellison showcases the music of Taylor and Mingus, then explains in the most diplomatic and careful way (while quickly surveying the history of jazz) that while this is the new thing, he is not that into it, and he could especially do without the critics who fawn over it — because he fears it might end up obscuring a deeper, richer tradition. In a sense, he’s not criticizing the musicians, so much as the critics. Here is one of the key things Ellison had to say. Right or wrong or somewhere in between, it deserves to be taken seriously because of his experience and expertise:

Any critic from outside this tradition must of necessity fall back upon his own values and thus he may be unprepared to interpret what he has heard, even though he might himself be a trained musician, for he is likely to confuse the motives of jazz with those of classical European music. It has been such outsiders, well-meaning to a man, who sponsored the false-consciousness of the new experimentalism in jazz. They were also promoters for the cult of intellectuals who imposed their romanticism on the new jazz much as the early pioneers had imposed their own romanticism upon the figure of the American Indian. Now, beneath this romanticism, and beneath all experiments lies a reality of life and experience which nourishes the beginning of jazz and will continue to nourish its future life. It is this reality, notwithstanding European serious or respectable touchstones, which will provide the true standards of its validity.

(That’s my transcription. It was never published). Then, fifty years later, Brody overlooks these comments, yet asks why Ellison “despised” modern jazz and suggests Ellison couldn’t finish his second novel because he was tormented by modernity (an odd thing to say about the author of Invisible Man). (I published a theory of why Ellison did not finish it. I also respect the compelling theories of Michael Szalay and Barbara Foley. I think the truth was probably a combination of causes outlined by me, Szalay, and Foley — and the differences between our theories and previous ones is that ours are based on painstaking engagements with texts, not psychobabble speculation.) But the bigger point here, I think, is that Ellison was the prime mover of the program itself, thus capturing Taylor, Sunny Murray, Mingus, et al., on film in that moment. Ellison put Cecil Taylor on TV in 1965 playing the piano as a string instrument. The piece he performs is titled “Octagonal Skirt and Fancy Pants.” Taylor explains his perspective. I think it’s an extraordinary artifact and I think Brody’s skewed representation of it probably stopped people from going to the Jazz Museum to see it. (It was available to be viewed every day for several months.) I have anecdotal evidence that it made an impact when aired. This was pre-cable. It went to millions of households. Albert Murray, by the way, is in the credits as a consultant for the three documentaries Ellison made or pushed to get made that year. (Of the other two, one was on Dizzy Gillespie and one was on Ellison himself.) Murray and Ellison were present at the creation of public television. Such artifacts should be understood in their own contexts instead of being put on trial fifty years later. The interesting point, the reason I tracked the film down (a long story and huge effort, for which Brody gives me no credit), and the reason the National Jazz Museum in Harlem paid for a license to show it as part of its celebration of Ellison’s centennial, is not to say “look upon Ellison’s sacrosanct opinions, ye mighty, and despair,” but to highlight it as a prismatic artifact of a moment, through which Ellison, Taylor, Sunny Murray, Mingus, and Williams — along with jazz criticism, jazz’s reception, public television, mass culture, and so on — can all be studied and appreciated in context. Incidentally, as Brody notes (and as Arnold Rampersad documents in his biography of Ellison), Ellison and Williams had a falling out shortly after this production, because Williams felt Ellison was just too stodgy and standoffish toward new music, but Williams and Albert Murray went on to work very closely together on jazz projects at the Smithsonian throughout the 1970s — I think that says something about the difference between Ellison and Murray on later jazz.

That’s the backstory behind his criticism of Murray?

Yup, well, that’s where he was coming from in his essay on Ellison, with whom he conflates Murray far too much. I’ve written a handful of negative or mixed book reviews and I’ve received a few mixed reviews. People have replied to me, and I know it’s tempting to reply. Normally I never would, but since you asked, there is something especially odd about his review and there is a larger point to be made about the angle it’s coming from. Brody said Murray was not really a jazz critic. Fair enough. I mentioned to him on Twitter that indeed, he’s right, Murray did not want to be considered a jazz critic: he never reviewed a performance or an album. Murray discussed this very point with me. He wasn’t a work-a-day critic. He did see himself as a critic in the sense of being a mediator between a work of art and the uninitiated — but that’s not what Brody meant, and I get it. What I was most annoyed with, more so than the piece itself, was the social media headline, which was “Beware Critics with Theories,” (but then, of course, he says Murray was not a critic). The headline “Beware Critics with Theories,” with a big photo of Murray, then goes out to millions on social media and can be read, subtly, if quickly scrolling, as “Beware: Murray.” The piece was strange in a variety of ways, from its version as originally published being constructed around a misattributed quote (said by Ellison, not Murray, which I pointed out to Brody) to its stumbling over its own logic, to feeling somewhat more hostile in its second published version, despite Richard’s generous comments on Twitter, where he offered extensive, kind praise for Murray and the book. I think the piece is fascinating because it is reflective of a lot of ambivalence out there about Murray from the age group for which the avant-garde was new and exciting. I told Brody thanks for paying attention, and for his nice comments, and I mean that. The day his piece came out was the day of a panel at the Jazz Museum for the book’s release, and I invited him to join us for a friendly debate. He had other plans, but he knew he would have been warmly welcomed to debate.

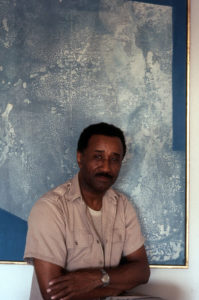

Murray in front of “With Blue” by Romare Bearden (1962), which hung above the Murrays’ dining table for decades. © The Albert Murray Trust.

What was Murray’s problem with the avant-garde?