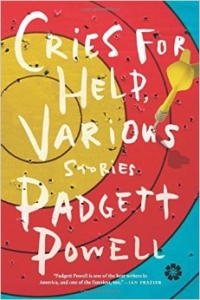

The title story of Padgett Powell’s recently released 44-story collection, Cries for Help, Various, locates us in the spaces of our speaker’s distress. Writing from France, our narrator extrapolates on cowardice, his own desires, and a fat boy skipping down the street trying to get a donation. In the story’s second section, “Cry for Help from Home,” our speaker’s father, a beekeeper and gambler, loiters on a garden wall where two women find him and want to keep him as their own. This itself does not irk me. I am romping around in Powell’s mind, exploring his brand of emotional turmoil which looks a lot like being a grown man sulking: “It is quiet in this nice house in France. Send me some money, you people. I am just like Robert Crumb, who has retired to south France, except he can draw.” Moving into the final scene, our speaker “jogging along lightly, nude” avoids two girls in wheelchairs exercising and a woman with “rouge silver-dollar areolae in an open shirt,” causing him to assert: “Man. Locating succor is getting hard.” The narration is voyeuristic; Powell’s story does not acknowledge anything about these female figures aside from their different ability, and nakedness. Further, the speaker aims to avoid engaging with these figures altogether, which I find troubling. Powell uses, or carelessly throws, these images around as tools for exploring white male emotional distress. Powell is making gestures away from a stauncher narrative with its visible arcs in favor of more irregular structures, however he maintains an attitude of avoidance and disengagement with characters other than the speaker. This is a tired move, and while Powell might be adept at a messier kind of storytelling, these images are slapdash, disengaged.

While Powell’s disengagement is unnerving, what is somewhat infuriating is a lack of critical response to his blatant sexism. Reviewers praise Powell as a visionary and kooky weirdo. The Rumpus’ David Byron Queen says, “With Powell we’re safe in the knowledge that there is someone out there who senses what’s ‘off’ about modernity and, regardless of whether any real sense can be made of it, demands that some hilarious truth be wrung out.” I disagree, I find Powell quite out of touch and find his scope too limited to his own perspective. Powell’s work reads as interested in what’s absurd but also as entitled and reductive.

Powell jerks readers between long and short prose, irony and sincerity, slapstick and metaphor. His work is markedly strange in his selection of images and non sequitur, sharp fake outs and undercutting. I find this admirable to some extent, but question to what extent he is being original. These stories are in the same vein as Donald Barthelme (one of the book’s two dedicatees, Powell studied with Barthelme at the University of Houston): descendant of surrealism, very postmodern, extremely compact, quite political at times, more incidental than symbolic. Powell is similarly playful; he delves into fun metanarrative philosophies. For example, “Joplin and Dickens” places Janis Joplin and Charles (“Charlie”) Dickens in the 20th century as primary school classmates. Powell’s voice self-consciously interjects almost immediately in the story, “Oh my this is poetic. Let’s abjure poetry because the conceit of this — Janis Joplin and Mr. Dickens a century out of his time — is already inane. We will stick to the facts and try not to be pretty.” This move to acknowledge the fiction of the story is intriguing alongside Dickens’ long-winded classroom speeches, a tension between necessity and beauty.

In the very short story “Love,” the narrator obsesses over the feeling of meat being jammed into the crevices on the soles of his shoes. He frets over his overall discontent with his inability to clean his shoe soles and general shoe sole tread design. This narrator asserts, “I am going with the flow mostly here. I am mostly going with the flow here, I mean. Trying to, with meat on my shoes. I know a poet named Rachel.” Turn the page and encounter a sharp turn: “September is my yellow month. I can be down in the mouth but not blue in my yellow month. Rachel is pink. I am not going to mention her again, at the request of one of my friends.” Powell’s skill lies in his ability to make a story feel finished or complete by virtue of what is not present, or by the presence of nonsense. “Love” might succeed because of its non sequiturs, which are perhaps interesting for people accustomed to more conventional, causal structures.

This collection includes odd little micro-narratives often only a page long or much less as is the case in “Longing”:

The kind of exhaustion I am talking about is, simply, or not simply, the broken heart. It makes you long to hold hands with someone you have not hurt who has not hurt you. This longing would be immediately and hotly extant if a dark girl offered you a cup of flan.

Again, as we see with the title story, Powell is careless in his image selection and appears to merely jot down this “dark girl” as a means of feeding the narrator’s interest in having a feeling of longing. It is not unusual for Powell’s narrator’s to be off-kilter or louche, Powell tends to treat his narrator with greater sincerity while their strange situations become fodder for his development.

Powell’s more expansive stories are at least as strange; they include a brief tale of a woman receiving porcupine earrings as a gift from her husband, a narrator wearing a “Taupist cold-cut shirt” (read: a literal meat shirt), a secret agent daughter, and a trio of Cold War fantasy stories which feature Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin. “Yeltsin and Canaries” is a glimpse into the swirling mind of the title character who tells us about the weird oddities he’s acquired (a toilet kit, a leech preserved in saline), “all in all a handsome if unusual accoutrement for a traveling dancing nuclear man.” Yeltsin is horrified at his fingers, which are somehow shortening which makes carrying his birdcage and other items increasingly difficult. He focuses on concealing his hands (“small stubby hands do not attract chicks.”) and dancing, “the meateaters meditation.” Yeltsin is a bird-crazy goon, moving “room to room in the free-market world.”

Powell’s collection is a constant minefield of bizarre images. His sentences are elastic; his syntax is very unusual at times which makes Cries for Help engaging. Some might find the pacing a bit haphazard, or sometimes the order of stories a bit curious but I think that this disjointedness is perhaps called for with stories that grapple largely with issues of unfulfillment and alienation.

I admit, I did enjoy Cries for Help, Various on the first read, though I remain perplexed but not surprised that it is part of a long tradition of while male writers doing as they please for the sake of representing the feelings and revelations of people categorically like them. While I am interested in Powell’s experimental mode and find some of his work quite entertaining, I am skeptical of writing him and his sexism off as simply “weird.” The New York Times’ Teddy Wayne has said, “Powell published his first book in 1984, but he’s a Southern writer who would have fit more neatly into the previous decade (and maybe another region), when metafiction, arch surrealism and maximalist language reigned.” I agree with Wayne insofar that Powell doesn’t fit in, but more because Powell’s aesthetic can be read as stale and his message archaic or lacking nuance. With Powell’s slapdash sexism comes a sense of gross entitlement that belongs in the past with other absurd ephemera.

Miriam W. Karraker writes poetry and is pursuing an MFA at the University of Minnesota. She writes for Bitch Media and The Loft Literary Center. Some of her poems can be found at TAGVVERK.

This post may contain affiliate links.