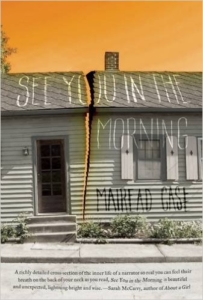

Mairead Case’s first novel, See You in the Morning, offers up an investigatory and introspective narrative space. Set within an unnamed Midwestern-ish town, “small enough to walk across in one morning,” See You in the Morning gives the inner life of an unnamed narrator during the summer before her senior year of high school. Though she spends time with her friends John and Rosie, working at a big box book store, going to see bands at house shows, learning to drive, and visiting her older neighbor, Mr. Green, most of her time seems to be occupied by her thoughts and questions and problems and revelations.

This narrator is an observer, a writer, and Case has chosen a form for the novel that supports an intense level of observation. Instead of chapters, there are vignettes. This is not the mode of the stereotypical teenage diary, though; this is the mode of someone hoping that by taking in everything, everything will be revealed. Throughout the text, we are reminded that writing things down might help — that writing might be the only way to understand. Early on in the novel, the narrator describes stealing a magnet from her new friend Louise’s refrigerator after an awkward misunderstanding on the part of the narrator about whether their time together was a date or not,

I guess it’s late. I should probably just go home. Alright, said Louise. I’ll drive you, but I’ll hop in the bathroom first. While she did, I peeled one of the magnets off the fridge — a fish on a checkerboard background — and put it in my pocket. I didn’t feel guilty about it either. It didn’t feel like stealing, just like writing it down. Writing down moves so I don’t forget them later.

The narrator has a lot of questions, experiences self-doubt and awkwardness, and often speaks of either not wanting to be in her body, feeling as though she’s lost her corporeal self, or worrying that she might dissemble into many pieces and not be able to come back together again. Despite this, her level of empathy often overrides these difficulties in her experience of the world and with others, and as reader I am given the feeling that she’s going to be just fine. Unlike a lot of texts that examine the teenage experience, Case’s novel is not limited by having the narrator focus only on herself. The narrator does look inward but she also is always looking outward. She cares how other people are feeling, and worries about them, strangers included. She is able to provide this concern, perhaps, because she’s already identified a certain sensitivity and poignancy within herself. The “angst” is there, but it is vibrating at a higher level, and so she can recognize it within others. She can even recognize a similarity with her boss at the bookstore, Steve:

We have a funny relationship. Steve’s twenty years older than I am, but we both live at home so there is a lot in common. Sometimes when I cash out, he slips in front of me to check the drawer. His shirt smells like dryer sheets and I can see his shoulder blades. Ever since Steve quite drinking, it’s like he got sharper. I keep thinking maybe I should call after hours, in case he’s sad.

The narrator is not the only character who exhibits this way of being in the world. There are several small acts of kindness described in this text. The adults in her life call her “sweetheart” and “honey.” Even something as small as dying her hair purple garners a note of concern from her dad, “Well, Dad said, okay. Just as long as you’re not sad. You’re not sad, are you honey? No, I said. No I’m not sad.”

She worries about her friends John and Rosie and takes care of them, though these relationships, as any group of three friends tends to be, are incredibly complicated, if also familiar and comforting. Through these relationships, Case is able to present such subjects as sex, sexual identity, abortion, bulimia, and depression, without them taking over the narrative. This is not to say that they aren’t taken seriously, but because we learn about them through the lens of this friendship, and through a sympathetic observer, they avoid stereotype and cliché.

Her friendship with Mr. Green, the eccentric neighbor, is perhaps the most endearing as she seems to be able to say everything to him she’s unable to say to John and Rosie. He also teaches her to drive, which, in the metaphorical sense, is what will allow her to leave this place she both claims as home and also understands as a place where she cannot remain:

When I graduate I have to go away, because otherwise I’ll just take care of everyone else. My head will get full, and I’ll start thinking about stories and people as facts, as statues or set, and then I’ll get tired eyes like John’s mom. Mr. Green has this calendar with buffalo on it. They look soft and stubborn. Rocks wrapped in brown carpet. If you stay, he told me, you will look like buffalo.

Her parents are rarely present in the text, but it seems evident, given the empathy and kindness of the narrator, that part of her character is due to their own kindness and support. The one conflict the narrator has with her mom (about learning to drive on actual roads instead of just in a parking lot) is so understated as to nearly be humorous: “Mom, this is stupid. I’m sorry but the world’s not a parking lot, and I need to learn how to drive. One mean burst from nowhere. It surprised us both, I think.”

Through Case’s descriptions of empathy (signaled nicely by the Mark Aguhar epigraph:) she also explores issues of class. There is a clear divide between the rich students who attend the university in the narrator’s town, and how “nobody talks to us like we matter,” as well as the narrator’s attitude towards her corporate bookstore job where she doesn’t care if people shoplift or sit all day. Yet, these differences, though sharply acknowledged, and often given a tone of frustration, are processed through this empathetic lens, and rather than what might be called “teenage angst” we get more of an attitude of acknowledgment and disappointment. This shouldn’t be confused with complacency, however — instead, it offers her yet another opportunity to figure out how to understand the world, the people in it, and where she stands. By viewing situations from other perspectives, she not only is able to discern whether her own perspective is valid, but also that most things are not black and white — and there aren’t always going to be easy answers.

This is much the same attitude that infuses her relationship with both John and Rosie. John is given more time within the narrative and we learn that he also takes care of the narrator in small, kind ways. Yet, this is perhaps not enough for her. Towards the end of the novel, the vignette form, with its various modes of description of events, dreams, memories, and ruminations, starts to break down, both in terms of syntax, as well as a movement to the epistolary. Part of the reason for this shift is due to an event that the narrator can’t seem to reveal to anyone else. She is worried that she might be pregnant after a one night stand with a stranger, and though she wants to tell John, she also has decided that maybe she needs to wait until she’s sure, because, “[i]t is helpful, when you are sort of scared, to set a date when you should be really scared. Before that it’s fine. I want to tell John, but also I don’t. It complicates everything.”

But the other perhaps more important facet of this shift, is that this event seems to have revealed another aspect of her relationship with John. Namely, that she is unwilling or unable to put herself in a vulnerable position with him:

Dear John,

When I think about where I live after school, I can’t see anything but not here. And I don’t watch movies with anybody else so I want you to come too. I felt weirder not telling you

Dear John,

It’s worse if I never say anything, so

Dear John,

Maybe this is dumb but otherwise I freeze

With the direct address to John and the incomplete thoughts, the narrator reveals more disorientation — seems less sure. Without an audience she is free to say and think whatever she pleases, but even when it is her closest companion, this idea of audience starts to halt her thoughts and her language — it starts to feel like she is censoring herself, and that maybe, despite her love, she needs to get away from him just as much as she needs to get away from the place she currently calls home.

Despite this shift in the mode of narration, the continued rumination on faith remains present. At various points in the text, the narrator describes going to church, and a belief in God, but also questions how some of the people in her community interpret the Christian teachings, especially when it comes to abortion and homosexuality. But it also speaks to a different kind of faith, especially when she describes how going to see bands play at the house shows are also a kind of church for her. Additionally, there is the faith of becoming what one needs to be. Even in the more fragmented thought that the letters provide, we get a sense of this:

Dear John,

After the bookstore I have no idea how I’ll make money. But I’m not worried

The novel’s title itself suggests this as well. There may be no other phrase that offers such comfort and faith than, “see you in the morning.”

The narrator’s wisdom and insight often belies her status as a teenager. Teenagers tend to be a rather dismissed group, and it seems that their stories, or any “coming-of-age” tale, is often relegated to the shelves in the Young Adult section — as if teenagers, or young adults, are only relevant to themselves. What we learn in Case’s novel is that this process of discovery — of the self, the world, of others — is continuous. It may not necessarily end once we reach adulthood. In reality, all of us, regardless of our age, are still trying to figure things out.

Sara Veglahn is the author of the novel, The Mayflies, (Dzanc 2014). She lives in Denver.

This post may contain affiliate links.