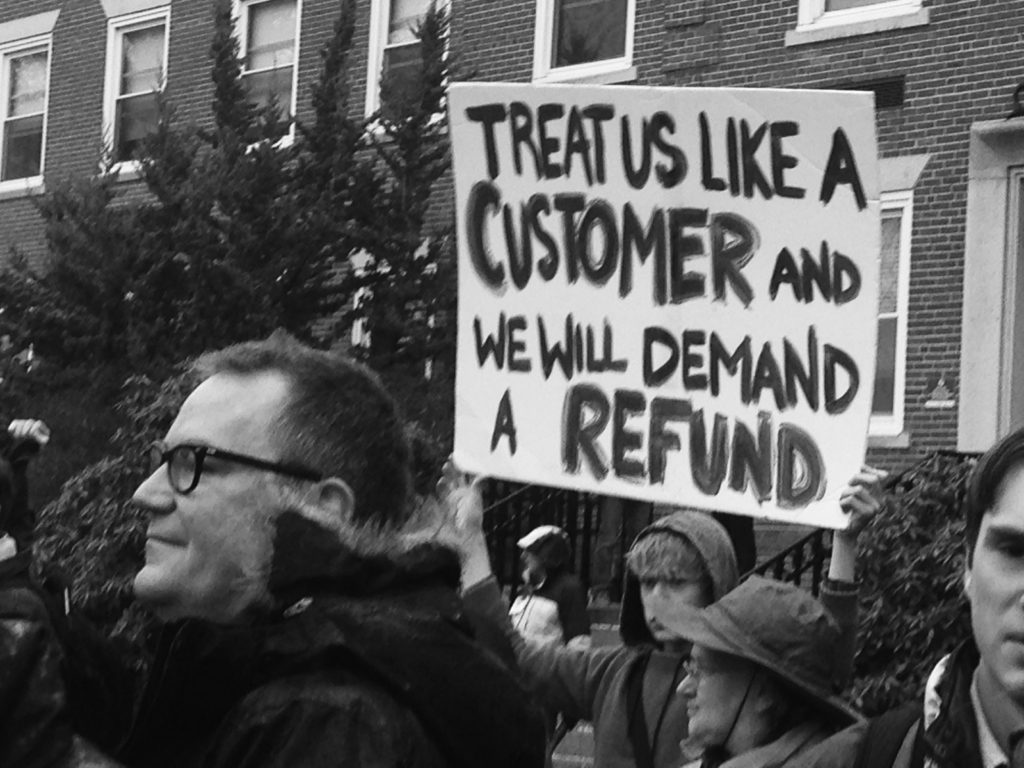

Students and faculty protest budget cuts at the University of Southern Maine. (Photograph by Nika Knight)

On a cold and rainy day in late November, a group of University of Southern Maine students and professors clad in dripping plastic ponchos cried out beneath the gray New England sky: “What do we want? An education!”

The drama that took place on the damp campus grass is yet another iteration of what has, since the 2008 recession, become a well-worn saga. Drastic budget cuts nationwide led states to steadily raise tuition or cut programs — or both — at public universities.

But while the economy has improved, the situation at many state universities has somehow continued to worsen. The austerity measures introduced by the free-fall of the market in 2008 precipitated a change in culture that allowed states and administrators to radically alter an institution that had once seemed relatively unchangeable.

At the University of Southern Maine, those drenched students were irate because the university’s interim president had rung in his tenure with wide-ranging and deep cuts to core programs and tenured faculty. David Flanagan, a former power company C.E.O, was appointed last July to temporarily head the university. His cuts were ostensibly for budgetary reasons: the Board of Trustees issued a dire prediction of a $16 million budget shortfall for the fiscal year of 2016, caused in large part by declining enrollment state-wide.

The cuts are presented to the public as inevitable. Yet faculty members, who say they have been shunned from the decision-making process, are by and large challenging that characterization. Many have argued that the school is not, in fact, in any financial trouble at all; others have questioned why the school failed to lobby for more state funding before cutting core programs.

These changes and the rationale behind them are, of course, not unique — the cutting of humanities programs in favor of business and STEM degrees is a nationwide trend. But it’s worth looking at a few of the most recent examples: a close look reveals that the reasons behind such cuts are backed not by the pure arithmetic of budgetary restraints but in fact by an entrenched and quixotic neoliberal ideology.

USM is a particularly resonant example, not just because of the harsh nature of the cuts but because of its locale: it was a politician from New England, after all, Justin Smith Morrill, who first proposed the land-grant system for state colleges in 1862. A native Vermonter and the son of a blacksmith, Morrill had never had a chance to pursue higher education — he only reached the first year of high school — and regretted it all his life. Today, public universities issue about 65% of the country’s bachelor degrees. It’s worth keeping in mind all of the Morrills that exist out in the world today, and looking at how the institutions built to serve them are being reshaped for other ends.

The American Association of University Professors has publicly condemned the changes at USM, questioned the financial picture presented by Flanagan and the Board, and in January initiated an external investigation of the administration’s decision-making process. As a result of the widespread cuts, the American Studies Association recently included USM in its “Scholars Under Attack” project, an online map of U.S. universities that the organization considers examples of “assaults on academic freedom.”

During the November protest, one professor at the bullhorn denounced Flanagan as alternately “a hatchet,” “a vulture,” and “a hyena.” Another lamented that she was helping her daughter transfer elsewhere to finish her degree. A Master’s candidate in applied medical sciences, whose program was one of the first to go, described his personal appeal to the president — he claimed that Flanagan responded by challenging him to “show me the check” from a private corporation willing to subsidize his degree.

One protester I spoke to, Katie Zema, was a 22-year-old sociology major. She is a transfer student who decided to forgo a degree at the pricier, private Mt. Holyoke College in favor of the more affordable option at USM. She aims to someday work with women who have been incarcerated. She said that some of her friends at USM hope to work with the homeless population and victims of domestic violence. She observed that “it’s work like that that society needs, and when they cut these programs, it’s affecting those people.” She told me that some students in her major were now having trouble finishing their degrees on time, because so many professors had been fired and courses canceled. “I feel exhausted,” Zema said. “I never thought that [an education] would be something I would have to fight for.”

The campus has been mired in strife all year.

Of course, President Flanagan expected blowback. And so to deflect his detractors, he’s framed the extensive cuts as a paradoxical boon to the school and the surrounding community. The school will be transformed, he said in a local op-ed announcing the changes, into a “metropolitan university.” The article went on to define what he meant: “Universities with such a mission are called ‘metropolitan’ universities because they sharply contrast with ivory tower universities that are set apart from local communities in their mission, mindset and remote, idyllic locations.”

This is an odd distinction to make when it comes to the University of Southern Maine. Part of the University of Maine system, the school is spread across three campuses, only one of which features residence halls. The median age of its student body is 28. It has for decades attracted non-traditional students; like many state and land-grant institutions, it has always been designed to do so. About half of its students attend part-time, and many juggle family life and jobs with the demands of their education; only 10% graduate within four years. Many students are the first in their families to attend college. It is far from “set apart” from local communities or in a “remote, idyllic location.”

And it’s hard to see how the cuts make the university somehow more “metropolitan.” Flanagan and the university’s Board of Trustees have entirely cut the geosciences major, the undergraduate French program (in the state with the largest Franco-American population in the country), and master’s programs in American and New England studies as well as the aforementioned applied medical sciences. The history, English and philosophy departments are being consolidated into a single “Humanities” major, and programs such as computer science, physics, and sociology are suffering far-reaching faculty cuts, drastically reducing class offerings in those disciplines.

There is a widespread feeling of confusion and betrayal in response to these changes, which is only exacerbated by Flanagan’s invocation of the “metropolitan university.” Many are skeptical. At the November protest, one student took the mic in order to pose the rhetorical question: how exactly are Flanagan’s cuts to USM’s “Community Planning and Development” department intended to improve the university’s connection to its community?

These students felt their school was transforming into a hobbled, lesser version of itself, and they couldn’t understand why.

* * *

The rationale for these changes isn’t rational: the budget cuts are part of a broader, national attack on humanities, the arts, social justice and social welfare in favor of STEM and business fields no matter the cost. This narrowing down of program offerings reflects the popular neoliberal mentality that favors economists over artists, businessmen over social workers, profit over morality.

While sometimes difficult to pin down in public discourse, broadly speaking neoliberalism is an economic philosophy that advocates for an ever-expanding private sector coupled with a shrunken public sector that never interferes with the goings-on of an unregulated free market. It’s a more extreme, more radical version of the laissez-faire concepts invented by Adam Smith. It is the reigning philosophy of our era, and it permeates our politics and our culture: it is evident in the ongoing expansion of privately-run charter schools, for-profit prisons and foster care systems, and free trade agreements like NAFTA, as well as the broad mandates given to the IMF and the WTO to undemocratically reshape entire nations.

In the context of the university, it means favoring private funds and profit, which is veiled as pragmatism, over all else. To fulfill a neoliberal mandate at the university requires sacrificing disciplines deemed less pragmatic (the humanities and social welfare programs are usually first on the chopping block) in favor of those deemed more pragmatic: business, accounting, and STEM degrees, usually. (A degree’s pragmatism is determined by a discipline’s perceived potential to serve private enterprise and profit.)

As a result of neoliberalism’s disdain for the public sector, when it arrives in a public institution such as a state university it actually works to shrink that institution’s power and its reach. For example, rather than ask for more (public) funds from the state, neoliberal administrators tend to raise students’ tuition, fire well-paid tenured faculty in favor of hiring tenuously-supported adjuncts, and seek out partnerships and programs funded by the private sector, which then gives private corporations the power to determine curricula and programmatic offerings at the university. Given its grip on our society, it’s not surprising that neoliberalism is transforming the public university, and this trend has long been noted by academics, activists, public intellectuals and journalists alike.

Yet what has often gone less explored is that the manner in which neoliberals are trying to reshape public higher education exposes the idiosyncratic nature of their philosophy — that is, the way that a philosophy that claims to be the only way to shape society, an inevitable choice, for the betterment of all, is, in fact, almost always undemocratically forced, often mistaken in its predictions, and destructive in its outcomes. In few places is this more obvious than in those institutions created in the spirit of a particularly American democratic ideal: the public land-grant university.

Neoliberal ideals clash decidedly with what land-grant universities were created to do: The Morrill Land-Grant Acts of 1862 and 1890, which created many of this country’s largest universities, declared their intentions “to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.” In essence, they were to educate and thus elevate a largely uneducated, lower-class strata of the agrarian and rural poor into the more privileged echelons of American society.

When neoliberalism’s fervor for privatization and profit collides with the institution of the public university, which was constructed to fulfill entirely different ideals, the idiosyncrasies and hypocrisies inherent to neoliberal thought expose themselves. It also demonstrates the ramifications of such reforms: the elite — privately educated at top-ranked liberal arts colleges and universities — can continue to study whatever they wish and go on to enjoy the benefits and opportunities wrought by their broad and prestigious education. They can continue to be the ones determining the course of our culture via their work in the media, the art world, museums and politics — and in university administration.

The lower and working classes, the ones for whom a state school is perhaps one of few affordable options for a college degree, will be further confined to the supposedly more “pragmatic” degrees, which at USM, as an example, includes Tourism and Hospitality. Their work opportunities will be further limited by the perceived weakness of their universities’ names, weaknesses created and emphasized by the dramatic cuts introduced by neoliberal administrators.

In this neoliberal future, your hypothetical Bowdoin College graduate, having written her French department thesis on Maine’s Franco-American history, will curate the new exhibit at the Franco American Heritage Center in Lewiston, Maine, and USM’s Tourism and Hospitality graduate will simply sell you your ticket. Does that appear to be the fulfillment of the Morrill Acts’ intentions, the elevation of the working and middle classes, a shrinking of class divisions?

In an essay in the anthology The Insecure American, the anthropologist and activist David Graeber writes of neoliberalism,

Supporters of neoliberal reforms were usually perfectly willing to admit that their prescriptions were, as they often put it, “harsh medicine”, or that the effects would, at least initially, be “painful”. The justification was — it was Margaret Thatcher again who put it most succinctly — that “there is no alternative.” Socialist solutions having failed, and global competition being what it was, there was simply no other way. “Capitalism” (by implication, neoliberal capitalism) had been proven “the only thing that works”. The phrase itself is significant, since it shows how thoroughly we have come to see states and societies as business enterprises: it rarely seemed to occur to anyone to ask “works to do what?” Nevertheless, even if neoliberalism is judged in its own terms — in which success is measured almost exclusively by economic growth — it has proved, on a global scale, remarkably unsuccessful.

In the context of the public university, it’s obvious that the cuts at USM aren’t rational, pragmatic, or inevitable because, well, for one, the economics simply don’t add up: it is, for example, far cheaper to offer French classes than nursing or business classes (the former requires neither expensive laboratory equipment nor the high salaries commanded by business and accounting professors) and in fact at most universities the tuition dollars of humanities students often goes toward subsidizing the expenses of pricier disciplines. Much has also been written about the flexibility of humanities degrees: it would surprise no one to note that holders of degrees in history, literature, and philosophy are to be found in large numbers in the upper-class professions of finance, medicine, law. Indeed, a crude cost-benefit analysis across the various disciplines would quickly reveal that a truly profit-driven university might only offer classes in the humanities.

It bears repeating: these sorts of cuts are ideological. And for the sake of our country’s indebted public university students, they must be exposed as such.

* * *

Another good example of the idiosyncratic nature of such changes took place last spring in Chicago. The University of Illinois in Chicago, or UIC, cut its master’s program in Elementary Education. The program had a rare emphasis on social justice — it was the only one of its kind offered by a public university in the region.

A friend of mine, Savannah Mirisola-Sullivan, graduated from the now-extinct program, and told me that the announcement surprised faculty members and students alike. Much like the changes at USM, a recently appointed, then-interim dean — who has since been made permanent — initiated the wholesale cancellation of the program. According to her and other graduates, his stated reasons for cutting the Elementary Education program included “austerity” and to reduce the school’s “teacher education footprint” — “seemingly likening teacher preparation to carbon emissions,” as another graduate wrote to me, “a point of view that doesn’t seem healthy in a college of education.”

When we emailed about it, Savannah dismissed the austerity argument nearly wholesale. She argued, “Using austerity as an argument ultimately doesn’t make sense, as our program was one of the most successful in the college (especially when you look at how many students are able to find jobs directly after graduation).” In 2013, over 200 students from her school took the qualification exam to teach in Chicago Public Schools. She continued, “Our program had dozens of applicants, as opposed to programs that are under-enrolled (that semester our program was cut, another that was kept on had only six applicants) . . . We shared professors with the undergraduate program, and thus were not a particularly costly program.”

In response to the rationale of reducing UIC’s “teacher education footprint,” Savannah said that “Moving away from teacher prep . . . is an inherently political move in a city that is known for shaming its teachers, de-professionalizing them, and blaming them for the achievement gap.”

Savannah’s first year of graduate school coincided with the mayor’s closing of over 50 public schools, nearly all in predominantly African-American districts. She argues that in that context, the cancellation of her program — which trained its students to teach in the very schools the mayor was shuttering — “fits more squarely into a narrative of disinvestment from black and brown communities.”

Without an affordable, public master’s degree in elementary education, public schools in Chicago (already such a neoliberal battleground) will lose out on the diverse, social-justice-oriented teachers that the program had nurtured for so long. The change, like all of these cuts to public universities, will be felt in the community for years and years to come.

* * *

There are many other egregious examples of so-called “pragmatic” changes to public universities around the country, yet none are so bizarre as those in Arizona. The state’s Tea Party governor and extremely conservative legislature has cut the state’s contribution to Arizona State University by more than a third since 2008. In response, the school has cut or consolidated most of its non-STEM programs, eliminated over 100 faculty positions in the process, and tuition has hiked to near private-university levels.

As of this writing, there is little that addresses this transformation on the school’s website. Instead, when I first visited it several months ago, Arizona State was announcing a different change: under the headline “shared strength,” it declared the addition of a new business school to “the ASU knowledge enterprise.” Except this new addition, the Thunderbird School of Management, was not new at all: it’s a private school that has been in operation since the 1940s, and it has been in financial turmoil for the past several years. It ended the financial year of 2013 with a loss of over $8 million. Yet Arizona State, ignoring its own extended crisis, is rescuing it from ruin.

And so the same school that raised in-state tuition by 70% between 2008 and 2013 to cover ever-waning state contributions to its budget is spending over $20 million to acquire a second business school. Because, of course, to make the whole thing even more odd, ASU already has the W.P. Carey School of Business — although it promises not to offer competing MBAs. As Bloomberg Businessweek put it, while Thunderbird is obviously benefitting from the deal, “ASU’s motivations are less clear.”

Yet perhaps those motivations are clear; perhaps they’re simply nonsensical. The university administration’s slavish attachment to the concept of profit and private enterprise has culminated in what is, in fact, a ridiculously poor business decision: to spend $20 million the university doesn’t really have to purchase a second, redundant and seriously indebted school of business which will not make the university more money. The deal is yet another expression of a feverish devotion to the concept of business (and business schools) and an accompanying disdain for other, allegedly less profitable disciplines. (Forget even suggesting that profit and its pursuit should perhaps not be the sole guiding philosophy of an institution for higher education.) These choices are made at the expense of the very ideals — pragmatism, austerity and profit — that administrators so love to trot out when they demand that students and faculty accept their radical reforms as inevitable outcomes.

Actual austerity measures, that ostensibly beloved neoliberal program, are often rapidly abandoned by administrators for the sake of what’s meant to naturally arise from them: expansive, perpetual growth. But that growth is often forced through in the same manner that the draconian cuts were: unilaterally, undemocratically, and in what appears to an outsider as an arbitrary fashion. The expensive decision to acquire Thunderbird follows the school’s current “aggressive growth strategy.” As a part of the same strategy, the school has rapidly expanded its online degree offerings and funded new constructions on its Tempe and Downtown Phoenix campuses, including “two new Sun Devil Fitness Complex facilities.” And thus has one of the most underfunded universities in the country grown to be the largest.

It is a strange dual consciousness that is fostered: the public is expected to weather news of steep tuition hikes and severe cuts for the sake of grim austerity, but then, just days or weeks later, celebrate the same school’s Knowledge Enterprise, Aggressive Growth Strategy, Low Education Footprint, or its impending status as a Metropolitan University. Such buzzwords and jargon slip easily from one’s mind, deftly evading the inconvenience of hard definitions — and perhaps that is precisely the point.

* * *

The protest on USM’s campus eventually wended its way into a clay-colored building, where a Board of Trustees meeting was being held in a gymnasium. In front of a blue Huskies banner, a horseshoe-shaped table arrangement held the catered lunches of the agéd, prosperous-looking members of the Board. David Flanagan sat in a corner and gazed calmly at the ragged but enthusiastic group of students and professors as they shouted slogans and filed wetly into the gym. Eventually, some member of the board announced a fifteen-minute break — it could barely be heard over the cries of “Re-invest in USM!” — and the students converged on the tables.

Students took turns at the now Board-abandoned microphone, and described how the cuts were affecting them. Speakers included a Master’s candidate in computer science, a gender and women’s studies major, and Zema, the undergraduate sociology student, among others. As they spoke, the Trustees re-emerged quietly from the side of the gym, where it seemed most of them had disappeared to. I spotted David Flanagan, in a spotless suit, opening a crackling bag of potato chips — the Lays were proffered in a metal bowl on a nearby table. He munched them blithely as he watched students give impassioned testimonials to their USM education, looking as if he’d happily found himself front-row at a kind of free matinee. Eventually, a protestor took the microphone and offered it back to the Board of Trustees so that they could “do the right thing.”

The program and faculty cuts have only continued at USM since that show of student and faculty solidarity in November. In addition, the university has gone on to spend $1 million of the funds it saved via those cuts — funds that it had claimed would go toward balancing its budget — toward a widespread advertising campaign to attract more students. Despite the expensive campaign, undergraduate applications this spring were down 10% from last year.

In January, a spokesperson for the American Association of University Professors explained why it was investigating the school to the Portland Press Herald, noting that “. . . the kinds of changes that USM administrators are contemplating seem to be much more far-reaching than those we’ve seen before. It seems to me there is something else going on here — a wholesale reorganization of the university.”

Flanagan responded to the AAUP, a union and professional organization, in previous exchanges by claiming that USM is in compliance with faculty contracts. The faculty union, however, claims it is in violation of its collective bargaining agreement, and has filed grievances against the administration. Flanagan has also stressed that the AAUP has no legal bearing on the USM administration, which is true.

The AAUP released its scathing report in May. Among other criticisms, the report noted, “in its pattern of confining its communications with the faculty on programmatic matters to announcement of accomplished fact, the administration has ignored not only AAUP-supported governance standards but also its own published statements.” The report examined the University of Maine system’s finances and found them healthy, citing its high bond rating and “large cash surpluses and reserves.” It challenged the administration’s narrative that the cuts were in response to budgetary demands: To the contrary, the report concluded that the university’s decision to cut so many faculty members “represents administrative decisions to erode the full-time tenured professoriate.”

The university challenged the report’s findings and methodology, and again emphasized the organization’s lack of legal heft. It remains to be seen whether the findings will have any kind of effect. After appointing a new, experienced university president in April (who then swiftly resigned in order to return to the troubled university he had left behind), the university appointed another president, Dr. Glenn Cummings, in May. Cummings’ application letter emphasizes his support for Flanagan’s “metropolitan university” concept and notes his belief that “fiscal management becomes the baseline measurement from which every leader is judged.” He will take office on July 1.

A professor of economics and women and gender studies, Susan Feiner, ended her November speech at the bullhorn with a loud and defiant promise to “never surrender.” And in June, the AAUP followed up its damning report by formally censuring the university. The faculty union is also in arbitration talks with USM over the cuts.

Yet despite these ongoing challenges from students, faculty, unions and other groups, the administration and the Board of Trustees appear staunch and unwavering in their course, the hot wind of neoliberalism forever full in their sails, as they steer headlong into these treacherous waters.

This post may contain affiliate links.