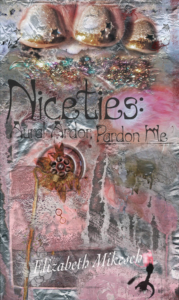

Elizabeth Mikesch’s debut Niceties, a wild and lyrical hybrid, is the rare exception in which the term poetic used to describe fiction isn’t hyperbolic. The stories feel like prose poems because they operate according to associative logic and sonic pleasures. Because Mikesch prizes sound over clarity, indefinite pronouns abound. The word it is chimerical and untraceable at times, as is the shape-shifting addressee. The opening piece “When We Were French,” is told thorough a collective voice of mothers describing their youth. The you being addressed is sometimes the women to each other, sometimes to the reader, sometimes to a nameless other. As they describe the past the speakers become the objects of memory:

We were sugar cookies, corsages, then whiffs of new perfume. We got lost in them, butonniered, and then cologned.

For the most part the stories stand alone and don’t seem to overlap in a coherent way, however the same images recur like talisman. Mikesch is interested in liminal states, particularly those of teenage girls, and the grotesqueries of the body. Teeth are often in braces; there is blood in these pages; and the sex is decidedly unsexy. Mikesch’s aversion to the color yellow resurfaces in the disparate stories, often sexualized, several times qualified as “spoiled.” She inverts traditional syntax, sometimes giving noun first then adjective, as is the rule of certain romance-languages. “Tidbits of fruit pale that swam in noontime cups.” Her words are hypnotic because she rebels against most rules of speech. Nouns are repurposed for verbs as often as they become adjectives, a litany mercifully without adverbs.

Lists fall into meter: flat-butted, spank-skinned, little-hipped, pimpled. It is this kind of move that might make someone classify the work as prose poetry, if such distinctions still mattered. My friend and I read the title out loud to each other many times, checking to see if it is in iambic pentameter. Niceties: AURal ARdor PARdon ME. We’re not sure how to scan Niceties, if it is dactylic or pyrrhic. NIceties (Stressed, unstressed, unstressed). NIceTIES (Stressed, unstressed, stressed). Whatever else it is, it is rhythmic and effective, a rebuff or balance to the second section’s title “Harshities.”

At its best Niceties reads like a series of metamorphoses. Girls become objects, not literally but transfigured by their own description. Sentences that begin prosaically give rise to transformation:

So, the dull wool of new school sweaters were bought for us in rough rouge, for the bleacherettes, clove smokers, snuck liquors we had become.

They shift again:

We were sisters with each other, onion-weepers, once we saw him, braiding maidens on the bleachers

Mundane moments of high school are made mythic, as if Daphne were turning into the laurel. But we do not linger on abstract comparisons for long, before being reminded of the solidly physical details of the world. Attention is paid to texture and scent in such a way that it seems devout; the body is a serious subject here. At times Mikesch is very funny. The speaker says of her brother in the story “Bucolics,” “I hated his gestalt.”

Sometimes the syntax strains under such inventiveness, and the wash of impressions don’t leave a trace on the reader when the story is done. In these weaker pieces the narrative is too slippery and the short story is over before we have a sense of speaker and other players. However Mikesch’s most successful stories, in which the protagonist’s voice is strong and strange without becoming unclear, are a pleasure to read. “I Go to the Trees” and “What Night Is” are two of the strongest pieces in the collection, standing as anchors toward the beginning and end of the book. They are told in the voice of a girl raised as a Jehovah’s Witness, who romanticizes everything occult. She hides tarot cards, longs to know her astrological sign, and believes her grandmother looks like a witch. She also cuts herself, descriptions of which are rendered in slant rhyme:

I sit outside classrooms while kids give allegiance. Not one intuits my lesions.

In “What Night Is” she and her brother called Other plan a clandestine birthday and speak to each other in their own sign language of “spider.” As in several of her stories, the protagonist is rhapsodic in her own head, in love with language, yet unwilling to communicate well with others. The girl from “I Go to the Trees” asserts

I am made of quincunxes, septiles and planets.

The words twist in your mouth, propelled by sparse dialogue, which allows for a breath between the incantatory passages of interior thought. It is at moments like this when Elizabeth Mikesch is powerful: when she’s more restrained, when the tumults of language have the necessary room to perform.

This post may contain affiliate links.