[Open Letter; 2014]

[Open Letter; 2014]

Tr. David Williams

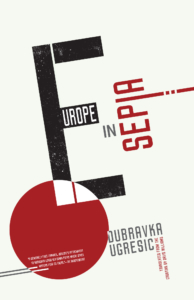

Europe in Sepia is the latest collection of essays by Dubravka Ugresic, a Croatian émigré author of eclectic fiction and non-fiction. Ugresic’s works tend to grapple with, among many other things, how an author’s originary facts — mother tongue, nation of birth, gender — affect the way their writing is read and understood. The impossibility of comfortably filing Ugresic herself under any easily described ethnic-national identity plays an important role in this line of questioning. Considering herself in the context of contemporary Dutch literature, for example, Ugresic, who lives in Amsterdam, writes “Where there is no longer literature; where it is no longer of any importance whatsoever whether anyone reads books so long as they’re buying them . . . I am forced to feel lucky to be noticed as ‘Croatian writer who lives in Amsterdam,’ and what’s more, to be envied for it.”

The question of language, citizenship, and literary tradition, however, is about much more than canny self-marketing. As Ugresic writes in the final chapter of the collection, “There’s a form of literary life we might call the ‘out-of-nation zone,’ best abbreviated as the ON-zone. I know a person who lives in that zone. That person is me.”

The “out-of-nation zone” is a space for those who cannot situate themselves within the context of an established literary history. As Ugresic writes, “For the majority of writers, a mother tongue and national literature are natural homes, for an ‘unadjusted’ minority, they’re zones of trauma.” Going on to explain how the translation of their work into foreign languages becomes a kind of “refugee shelter” for such writers, Ugresic specifies a position of alienation that in many ways defines her perspective throughout this collection of essays.

While every one of the 23 essays that compose Europe in Sepia independently addresses a unique subject and stands alone as a piece of writing, as the collection unfolds, Ugresic extrapolates on a number of interlocking themes. The position from which she speaks gradually becomes the subject of the book, as concerns over revolution and the writing life become intertwined.

Along the way Ugresic wrestles with the position of women in literary culture, Yugoslavian and Balkan politics past and present, and the inescapable entanglement of the Poet, Priest, and Politician. She tells anecdotes both comic and tragic, and recounts a wealth of eavesdropped conversations (“Spying on the everyday is half a writer’s job; the rest is creative filtering of the information gleaned”). At times Europe in Sepia feels like it could be placed in a bookstore display alongside other zeitgeisty non-fiction works offering perspectives on our contemporary revolutionary moment (Why is it kicking off everywhere?); at other times it seems more engaged with the persisting question of how to enjoy a writerly livelihood, recently addressed quite comprehensively in n+1’s MFA vs. NYC. But unlike most books that bring together the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions with Occupy Wall Street and the London riots, Ugresic is not interested in identifying a catalyst, signpost, turning point, or other narratively utilizable marker. She’s not interested in declaring the present to be exceptionally hopeful or hopeless. She’s interested, rather, in talking about the particularity of now as it scrambles out of the past and lurches towards the future — unpredictable, nonlinear, but worth observing with whatever amount of critical distance an author can access. Ugresic is interested in the committed losers, whose narratives might take on unfamiliar shapes, without so many peaks and valleys. She is invested in traveling the winding, bumpy back roads of the excluded.

***

Although it is a collection of essays, Europe in Sepia has a protagonist: Nikolai Kavalerov, a character in Yuri Olesha’s 1927 novel Envy, who Ugresic describes as “my brother.” Kavalerov is the spiritual mascot of Ugresic’s conceptual tableau, and Envy becomes a kind of ancillary text to Europe in Sepia. The novel is addressed at length in the essay entitled, “Manifesto,” with excerpted quotes also serving as epigraphs for each of the book’s three sections. Ugresic aptly explains why it’s so useful to engage in the kind of free-wheeling cultural criticism that clarifies the existing world with the lens of fiction: “Great novels are like blotters, absorbing the fundamental dilemmas of their epochs while blindly anticipating future ones.” We can find ways to read ourselves and our time by reading novels.

Envy, written at a moment when ideological narratives of history and the future were propelling reality with unprecedented power, is a novel of outsiders. As Ugresic points out, the novel hangs on the squishy symbolic motif of a pillow, an object of comfort that functions as a figurative life raft in the havoc of modernization and achievement.

Incorporating lines from Envy, Ugresic writes:

We’re on the bottom, and somewhere up high, high above us rumbles time (“Then for the first time I heard the rumble of time. Time was racing overhead. I swallowed ecstatic tears,” says Kavalerov), roars the modern world. Yet something tells me that this bed full of losers, each clutching his or her pillow like a life raft, will endure for a time to come, and that those above, that they are ephemeral, like the sun and rain that cast a rainbow above us, like the wind that blows golden leaves upon us, like the snow that covers us like a duvet, and then melts. . . . Of course one shouldn’t believe in such things.

If Ugresic has any hope for the future, this is what it is comprised of: the possibility that the most tenacious members of humanity might be the ones who lay low, who have decided to relegate themselves to the out-of-nation zone. Theirs is a different pace, they move at a bit of a lag. In Envy, Kavalerov is constantly delivering diatribes directed at various others who are either out of earshot or have simply chosen to ignore him. He is a muttering critic, but his heart is in the right place. Like the members of the out-of-nation zone, he isn’t trying to keep up because he’s already been left out. But he can keep track.

***

Coming from that out-of-nation zone, Ugresic, like Kavalerov, is able to stand at a slight remove from the chaotic now she is observing. She writes, “I am a foreigner, and I have my reasons.” She was born in a country whose borders transformed so dramatically in her lifetime as to make it nearly impossible to identify exactly which language she writes in (according to the cover, the book was translated from Croatian, but as she points out, Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin are all essentially indistinguishable). While the facts of her birth might be an accident of circumstance, how she positions herself within that given framework is intentional. As she writes, “Life in the zone is pretty lonely, yet with the suspect joy of a failed suicide, I live with the consequences of a choice that was my own.” At a certain point “foreign,” becomes as livable an identity as any other. It fits better not to fit anywhere.

This position, however, shouldn’t be understood as passive. Exclusion does not preclude participation. In Envy, as in Europe in Sepia, it is made explicit that there will be no overcoming of odds that culminates in power and glory and benchmarks of success. Ugresic is rightfully suspect of victors, just as she engages with the more monumental moments of the last few years without a hint of teleological hagiography. She writes, “Is the platitude about the inevitable triumph of artistic justice to be believed? Questions of justice are usually settled by the victor’s hand.” Distrust in the storyteller is a compelling reason to breakdown grand narratives. If you had the privilege of writing the history books, you probably got your hands dirty along the way.

Nonetheless, she dreams of action: “I extinguish my fears with fantasies about them, about the kids who will soon (yes, soon!) in their millions crawl from their ghettos, and fists raised descend on Wall Street, or wherever they’re needed. My fantasies, however, don’t hold for long…” This is a revolution of the frustrated and excluded. It might even come out of some ugly emotions — like envy — and the end goals may remain forever convoluted.

***

Towards the very end of the book, Ugresic asks, “What is the quality of a freedom where newspapers are slowly disappearing because they’re not able, so the claim goes, to make a profit . . . when publishers unceremoniously dump their unprofitable writers. . . .” She makes it clear that “freedom” isn’t something derived from governmental structures, and that tyranny can express itself in widely divergent circumstances.

But even if profit is our overlord, we can take solace in the fact that this strange book has made its way into mass circulation. The very knowledge that so many ideas can be packed together into such a modest assembly of words and pages, bouncing off each other with such widely reverberating ricochets, is heartening, and gives credence to Ugresic’s fleeting moments of hope. This odd conglomeration of offbeat but illuminating observations makes one think that with a little determination the bed full of losers might really endure for a time to come, and the victors just melt like the snow. Of course, one shouldn’t believe in such things.

This post may contain affiliate links.