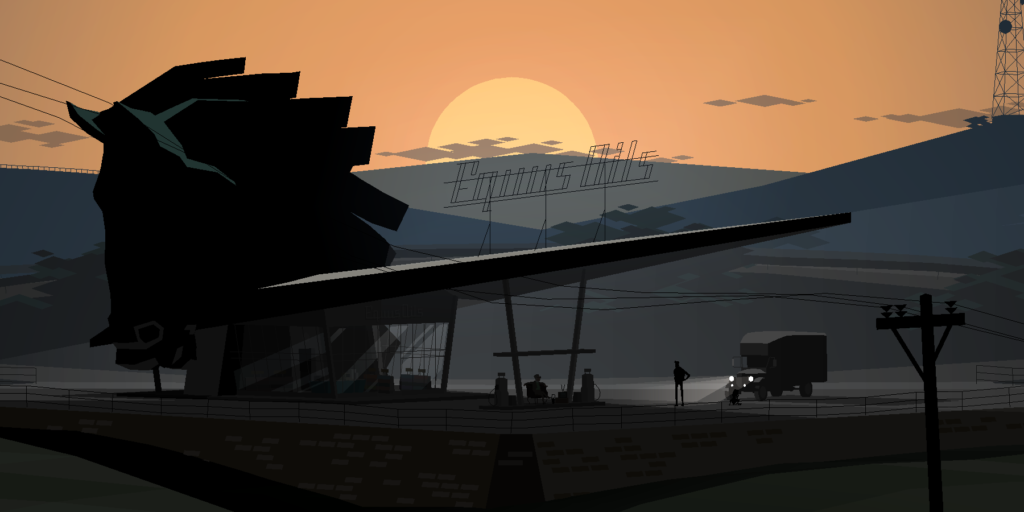

The opening scene of Kentucky Route Zero features the protagonist, Conway, and his dog getting out of a truck in front of a shadowy gas station. It’s dusk, and the sound of the truck’s idling engine fills the air alongside incessant bird chirping. Occasionally, the sound of passing cars cuts in from Interstate 65, which stretches across the background.

Kentucky Route Zero is a strange road-trip of a story that takes place along I-65, on that stretch in western Kentucky just north of Bowling Green, near Mammoth Cave. The opening scene paints the quiet isolation of the region and the plot builds on that, adding in healthy doses of tragedy and poverty. The narration and dialogue are full of Faulknerian lines. In the opening scene, the narrator tells us that. “It ought to be quitting time in this part of Kentucky, but the sun just won’t quit.” In a farmhouse kitchen, the protagonist sees a skillet that’s “seasoned with dust.” Later, a couple of men at work are described as “nearly broken.”

The soundtrack echoes this theme. At some points the music is minimalist and electronic. When a light switch is flicked on and fluorescent lights begin to “whine,” a celestial, wispy tune drowns everything else out. Zero also features traditional bluegrass and folk music, including covers by the Bedquilt Ramblers of the Stanley Brothers’ classic “Long Journey Home” and Woody Guthrie’s “You’ve Got to Walk That Lonesome Valley ” (original vs. the game’s version). During another scene, the sound of a muffled hymn-singing choir comes through church doors.

Having brought these details together to recreate the southern world, Kentucky Route Zero proceeds to lead its audience on a western Kentucky journey that walks the line between magic realism and surrealism. Conway’s dog wears a straw hat. The first person Conway meets is seated in a cushily upholstered armchair between two gas pumps. The gas station itself is in the shape of a massive horse head. A man wearing a rack of antlers on his back is seeking a tragic venue for a tragic play. In the background, the scenery dissolves into geometric shapes. But between these absurdist liberties with the truth are gems of authenticity: a history of coal mine scrip currency, thoughts on academic anthropologists observing the local population, and a bait shop that runs a television repair business out of the back, complete with a sign that asserts “We do not sell digital converters.”

What makes Kentucky Route Zero unique is the fact that it’s a video game. Created by a two man operation out of Chicago called Cardboard Computer, it might be the medium’s first artistic homage to the South. During trips to visit the homeland of their southern girlfriends, developers Jake Elliott and Tamas Kemenczy became inspired by the rural scenery they passed along the way. The game is broken up into five planned episodes — currently Acts I and II are available, along with related short pieces entitled “Limits and Demonstrations” and “The Entertainment,” with the other Acts scheduled to arrive in the near future.

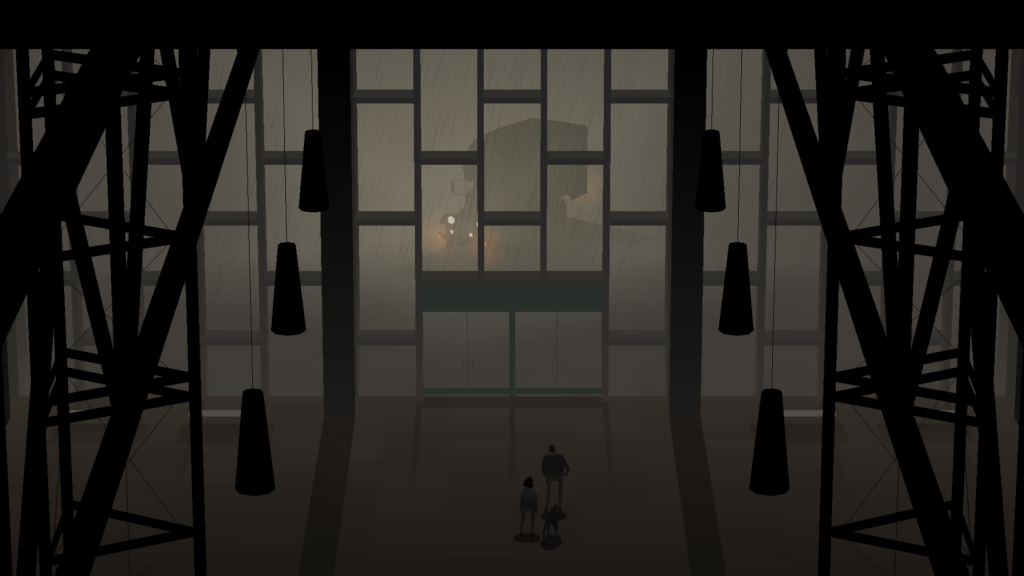

If the description I’ve given thus far sounds worlds away from the car crashes and gunfights you might expect in a video game, that’s because it is. Whether or not video games are “art” has been the subject of a good amount of writing, both academic and popular (including in Full Stop). It would be difficult to classify Kentucky Route Zero as anything but art, however. Players of the game will find themselves spending as much or more time reading text as performing actions. A meta-discussion about art and anthropology runs as an undercurrent throughout several scenes; at one point, Conway finds himself in a museum which contains low-income housing units, and people living in them, as exhibits. Finally, in the most recent piece released, “The Entertainment,” the entire gaming experience involves nothing more than the player sitting at a table in a bar as part of the set of a play. Your character is unable to move beyond looking around the room, and your only available action is to watch the play unfold, along with information from the director and the audience.

Your role as the game’s player is limited to picking destinations for the characters and deciding between lines of dialogue. It’s more like an interactive movie than a session at the arcade. (In the video game world, the genre most closely resembling Zero is the “point and click adventure.”) And the choices you make don’t determine whether you win or lose. In fact, it’s never clear if there is a right choice morally or in terms of advancing the story, and often it’s hard to know what impact if any a specific choice has. Instead, the choices you make become the story itself: the motivations of the characters, the tone of the conversation. As you follow Conway on his journey, your decisions can paint him as a determined delivery man, unwilling to rest until the job is done. Or, you might decide he’s more of a dreamer in an invested relationship with the road.

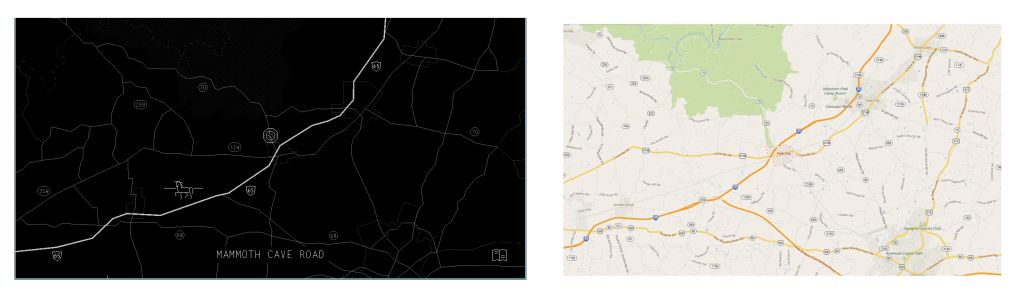

When you decide where to send Conway, you’re presented with a simple line map of western Kentucky. While the towns are not labeled, the roads are, so anyone familiar with the area knows right where the story is taking place. State highway 68 runs along the southern border of the game’s map, which means that part of the game takes place on the most iconic road of my childhood. For me, 68 ran between home and college, and it holds the memories of drives to grandparents’ houses and rendezvous with girlfriends. Zero takes these familiar thoughts and sounds and uses them to segue the journey into unfamiliar territory.

Kentucky Route Zero is a video game that exists in a murky middle-ground between a literary and a cinematic experience. Thus, it’s no surprise that the conversation about the game includes elements of both. At the 2013 Independent Games Festival in San Francisco, the game took home an award for “Excellence in Visual Art.” Reviews of the game frequently cite Gabriel García Márquez and use the term “magic realism,” a genre which is more associated with books than with anything digital. Another review compares the artistic direction of the game with Edward Hopper paintings. One of the developers, in an interview, referred to the game as a tragedy — which is not exactly the genre you imagine when you picture a teenager sitting down with a controller in front of a television. Kentucky Route Zero, along with a consistent niche-full stream of other games (recent examples include Dear Esther and Proteus) break from the traditional video game world of violence, sports simulators, puzzles, or fantasy escapism. Cardboard Computer embraces this mold-breaking. The trailer for the game features only music and a handful of scenes, with no description of gameplay. On their website, the game is described as “inspired by point-and-click adventure games (like the classic Monkey Island or King’s Quest series, or more recently Telltale’s Walking Dead series), but focused on characterization, atmosphere and storytelling rather than clever puzzles or challenges of skill.”

The creators of Kentucky Route Zero might not be from Kentucky, or even the South, yet despite this—or perhaps because it—they have created a work of art that resonates deeply with a certain nostalgic southern longing. Cardboard Computer accomplished this with accurate details and a compelling storytelling experience that evoke the idea of “home.” As a Kentucky boy now far from the highways of Zero, I found myself wanting more when the game ended. More of the music. More of the atmosphere. More of home.

All pictures of Kentucky Route Zero used with permission of Cardboard Computer.

This post may contain affiliate links.