Since its publication in April, The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner has leaped to the top of critics’ picks, summer reading lists, and office betting pools. (Does your office bet on book awards? My last one did.) It has kindled sincere discussions in our literary press about the Great American Novel—rare for any book, and even rarer for a book by a woman. But while its vivid language is widely praised, and its gender politics have sparked an Internet flare-up, few people have offered an interpretation of The Flamethrowers. If it’s such a great novel, then what does it tell us?

Here are five of The Flamethrowers’ big ideas.

1. The Fine Lubricated Violence of an Internal Combustion Engine

1. The Fine Lubricated Violence of an Internal Combustion Engine

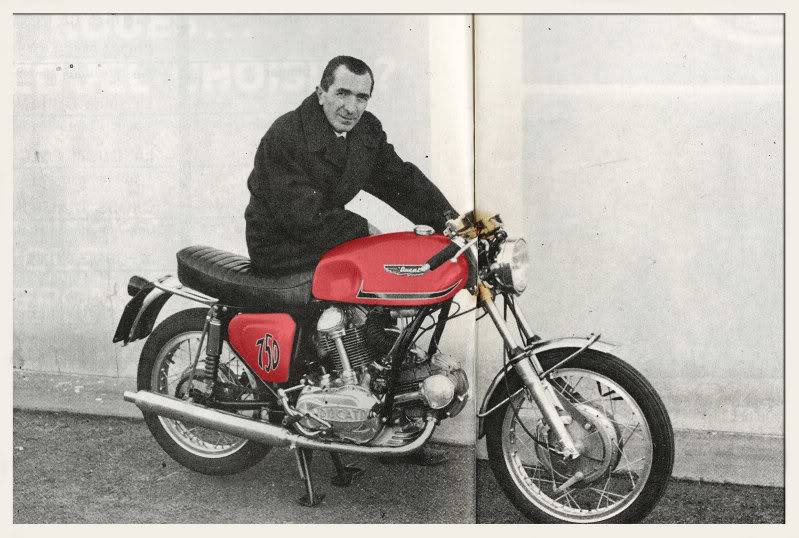

What if an ingénue arrived on the New York City art scene in the 1970s, embodying the Italian Futurist movement of the 1910s? That’s the unlikely premise of The Flamethrowers, and it provides the raw material of the book. Kushner uses the early chapters—with her protagonist Reno racing and crashing her motorcycle—to map out a relationship among engines, speed, violence, and art. So basically Futurism. But Kushner seems reluctant to use that word, as if it would define Reno too narrowly or imply an unwanted connection to fascism. That Reno should so unwittingly embody the values of a movement that took place in a foreign country, before she was born, is the central conceit of her character, which Kushner fleshes out by giving her a blue collar family that knows its way around engines, and by thematically linking her upbringing to T. P. Valera’s. (So much neon!) Reno uses her life to leave a physical mark on the world, and she calls this art. But the people she meets in New York City treat art like it’s a stunt, or a career, or a theoretical debate.

With her other major character, Sandro Valera, Kushner uses engines, which can be a means to personal freedom on an individual scale, as a metaphor for the oppression of the working class on a national scale. In New York City the line between art and politics is blurry. A working-class artist like Ronnie Fontaine can pander to his wealthy patrons at a dinner gathering, and a would-be agitator like Burdmore Model can flirt with political revolution under the guise of making art. But when Reno gets to Italy, she witnesses the real and violent consequences of politics. These are the so-called Years of Lead, when the Autonomia Operaia galvanized Italian laborers. Aided by a rather convenient turn in the plot, Reno is able to see the conflict from the front lines of Rome’s elite and from the vanguard of its working-class opposition. Remarkably, Kushner doesn’t frame the struggle in terms of fascism (although the Valera family is certainly on the side of fascists) or good and bad. Rather, she’s interested in examining “the difference between aesthetic stakes and political stakes,” or what David Ulin calls “the uneasy ways” that character and culture intersect. Kushner had real-life inspiration for the riot scenes. “By the time I needed to describe the effects of tear gas for a novel about the 1970s, all I had to do was watch live feeds from Oakland, California.” So Kushner imbues the fairly obscure subject of Italian labor strikes with contemporary urgency.

2. Nude Women and Guns

The misogyny in the novel is so brutal, casual, and unremarked upon that it seems to belong to an alternate reality as well as a different era, not so much a theme of the book as a historical fact, blunt and unavoidable. From Lonzi’s speech to his futurist comrades—“Women will be our pocket cunts. […] You take a break from machine-gunning, slip them over your member, love them totally, and they don’t say a word.”—to Stanley’s explanation of how the Motherfuckers got their name—“Because we hated women,” he said. “You think I’m joking. Women had no place in the movement unless they wanted to cook us a meal or clean the floor or strip down.”—to the song that Reno and Sandro dance to—“He Hit Me (and It Felt Like a Kiss)”—every male artist in the book seems to hate women, as if this were a prerequisite for genius. Sandro and Ronnie’s great friendship is forged over their shared obsession with a statue of a slave girl. Ronnie sums up the general attitude when he says of Reno’s best friend, “Giddle is like a piece of furniture, necessary but ultimately insignificant, something to lie down on occasionally.” Aside from the loose community of female revolutionaries in Rome, who broadcast a radio show for women called Everyday Violence (since women are experts), the book offers little resistance or comeuppance for misogyny.

Kushner has said that she “looked at a lot of photographs and other evidentiary traces of downtown New York and art of the mid-1970s” and she kept finding “nude women and guns.” Which makes sense, since her subjects are men obsessed with speed, glory, control, and domination. She said:

I was faced with the pleasure and headache of somehow stitching together the pistols and the nude women as defining features of a fictional realm, and one in which the female narrator, who has the last word, and technically all words, is nevertheless continually overrun, effaced, and silenced by the very masculine world of the novel she inhabits.

By depicting, but refusing to condemn, the rampant misogyny of the era, Kushner makes a non-statement that feels like a powerful statement of its own. She looks abuse in the eye and doesn’t blink. It feels like the novel is operating outside the notion of women’s rights entirely. Laura Miller says that Kushner “seems not so much to be defying the masculine prerogative in [literary fiction] as to be unaware of it in the first place.”

At a stoplight, a man in the backseat of a cab, a cigarette hanging from his lips, rolled down his window and complimented the bike. He wasn’t coming on to me. He was envious. He wanted what I had like a man might want something another man has.

3. A Person to Whom Certain Things Happened

“Unaware,” “unconcerned,” and “uninvolved” are all good words for Reno. When the English novelist Chesil Jones mansplains something to her, she lets him blather on. “Wide-eyed and even dangerously porous” is how James Wood describes her. Reno’s passivity may be disappointing to contemporary readers who expect a female protagonist to be more admirably plucky. While her inner thoughts are fully realized on the page, she stays almost radically uninvolved in major decisions that affect her life, such as whom to befriend, whom to date, and where life will take her. It’s as if Kushner recognized a common concern about female characters—their lack of agency—and decided to push it to the extreme. But Reno, paradoxically, makes a careful choice to take her hands off the steering wheel of her own life. For her, giving up agency is synonymous with being avant garde.

I come from reckless, unsentimental people.

I felt [art] had to involve risk, some genuine risk.

I trusted the need for risk, the importance of honoring it.

Chance, to me, had a kind of absolute logic to it. I revered it more than I did actual logic, the kind that was built from solid materials, from reason and fact. Anything could be reasoned into being, or reasoned away, with words, desires, rationales. Chance shaped things in a way that words, desires, rationales could not.

Reno’s closest friends encourage her to let life simply happen. This seems to have more to do with Reno’s identity as an artist than with her identity as a woman. Giddle sets an example by living the life of a downtrodden waitress but calling herself an artist, as if the only difference between passive suffering and artistic brilliance is what you choose to call yourself. Sandro says, “You don’t have to immediately become an artist. […] You’re young. Young people are doing something even when they’re doing nothing. A young woman is a conduit. All she has to do is exist.”

So Reno becomes a permanent third wheel, the “girl on layaway,” a “China doll” who makes a living by posing for generic photos, a woman often seen but rarely noticed. For Reno this is a practical stance, a way of viewing life as an artist would; of being frictionless, as she strives to be on her motorcycle. Kushner has said that “fiction is a space in which you can use naivety to bump up against ambiguities,” and Reno is certainly great at bumping up against ambiguities. Her naivety makes all interpretations possible; makes the plutocrats and gallery owners as sympathetic as the artists and laborers. This is why it doesn’t seem so ridiculous that Reno loves Sandro Valera but helps his brother’s killer flee the country. It’s no accident that the novel ends with Reno waiting, suspended, unsure how much longer to wait.

Even when people abuse and betray her, it feels wrong to think of Reno—the great believer in risk and chance—as a victim. Reno doesn’t see herself as an example of anything. “I didn’t have to be recognizably one thing,” she realizes. In a telling scene, Reno and Sandro watch a movie about a woman in a coal-mining town, and they offer very different interpretations.

The point of the film was not the stark life in a coal-mining town, although that was how Sandro had read it, the human element of industry. It was about being a woman, about caring and not caring what happens to you. It was about not really caring.

Reno is figuring out how not to care.

4. On the Scale of Individuals

If Reno and Sandro’s inability to agree on the meaning of the coal-mining movie suggests that people—even lovers—can see the same events in wildly different ways, then their friend Stanley’s parable makes the theme official. Talking to Reno about his marriage, Stanley describes a boy and girl who arrive at a train station. Mistaking the signs above the restrooms for the name of the station, the boy declares that they have arrived at a place called Ladies, while the girl insists the place is called Gentlemen. “It’s the same place,” Stanley says. “But they will never realize it.” Gender is important to his story, but the lesson is really about interpretation and solitude.

Despite the novel’s sweeping historical and international backdrop, Kushner stays focused on individual perspectives. Reno is drawn to the Bonneville Salt Flats not for glory, but because the challenge of setting a land speed record is so solitary, “each calamity or success on the scale of individuals.” Laura Miller points out that our whole experience of the novel—at least in Reno’s chapters—is internal: “So potent is the voice Kushner gives Reno that many of the book’s reviewers forget that the only character in the novel who can hear it is Reno herself; to everyone else, she’s just Sandro’s long-legged blonde girlfriend.” Even the Motherfuckers, despite their commitment to overthrowing the social order, revere a fictional manifesto that says, “What happens between bodies during an insurrection is more interesting than the insurrection itself.” Everything about the novel conspires to suggest that the only valid perspective is that of an individual.

This makes Adam Kirsch’s much-lambasted review of The Flamethrowers all the more amusing. Kirsch argues that the book received a warm critical reception partly because Kushner, a woman, wrote what Kirsch describes as “a macho novel,” as if its success were a result of its place within male and female hierarchies. He seems not to notice that Kushner has already scoffed at him. “A funny thing about women and machines: the combination made men curious. They seemed to think it had something to do with them.”

In a bildungsroman the protagonist’s experience usually reflects and responds to the primary issues of the age. But although it clearly has political concerns, The Flamethrowers remains stubbornly apolitical. Reno never truly connects with her times. When she finds herself feeling bad for the servants at the Valera mansion on Lake Como, all of her anxieties about systematic injustice dissolve into the conundrum of her individual perspective.

Later I realized [the servants] weren’t a big deal to Sandro because he didn’t register their presence as judgment. Only I did, which, as his mother might have pointed out, was a problem of class, of being from the wrong one, too low for a servant to feel I was an appropriate object of their attentions, for their flower arrangements and ironed sheets, and that was my problem, not hers or her servants’, and she was probably right. It was my problem.

Again Reno is the third wheel, an outlying individual in societies that are preoccupied with large-scale movements and revolutions.

5. The Outrageous Pretense of Innocence

So The Flamethrowers is about the abuse of young women and female artists, and how one young artist remains impassive in the face of such abuse by becoming passive, and how her individual perspective is more important than the conflicts and debates raging around her. In other words, you’re being had, so accept it, and learn to understand yourself and your society better as a result. That’s what reading fiction is all about.

As for making fiction—making art—The Flamethrowers suggests that it’s not much different from being alive. Sometimes all it takes is calling your job as a waitress an artistic performance. Or, like Reno, taking photographs of your motorcycle tracks in the dirt—as long as you can back it up with a good story and personal conviction. Reno’s best tutor in this regard, despite his being an asshole, is Ronnie Fontaine, who says that art, or dissimulation, or fiction, is a form of discretion; of withholding what would only serve to embarrass you, and advancing what is worthwhile. Making art is good manners—ironic, since he has terrible manners. In Sandro’s chapter the idea goes deeper: Discretion was a mode of survival. That’s certainly true for a new arrival like Reno, trying to make a career in New York as an artist. Revealing too much of your real self can be suicide. So living is art, art is lying, lying is discretion, discretion is survival. Even your innocence can be put to sly use, like half-naive Gloria standing in a box, exposing her naked torso to strangers. “But that was of course the joke, the outrageous pretense of innocence. Of passivity.”

This post may contain affiliate links.