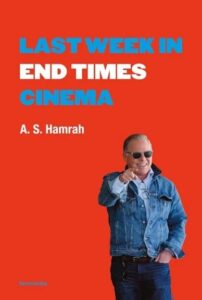

[Semiotext(e); 2025]

Show me what captures your attention, and I’ll tell you who you are. This, at least, is what a handful of teachers and mentors have told me, imploring me to keep an “idea journal” that, over time, will reveal the deeper structures of what I think, and therefore, who I am. The same might be said of the notes, musings, and headlines captured in Last Week in End Times Cinema, a bound collection of A.S. Hamrah’s homonymous weekly Substack newsletter from March 2024 to March 2025, published by Semiotext(e). Hamrah is the film critic for n+1, and more generally, a mordant critic of film as an industrially produced commodity as opposed to carefully hewn art (of course, like any complex thinker, Hamrah would probe at that simplistic dichotomy). Read through a “full year of wrong thinking, bad decisions, and man-made disasters” and you will get some sense of just how dim Hollywood’s lights and luminaries are.

Hamrah’s newsletter and book amount to a “doomscroll…of a very specific kind, in a concentrated form,” as he is the first to admit. No less than the social media platforms he criticizes, the book amounts to fleeting glances of the dire state of film, criticism, and culture. The chief villains, as one would expect from a critic with bylines such as Hamrah’s, in The Baffler, n+1, and The Nation, are structural: capitalism, for one, though Hamrah speaks with more granularity and point to the now always-imminent revolution in artificial intelligence, the crowding out of original stories by an endless parade of sequels, and the popular taste for pre-chewed pablum over the erotic pleasures of heuristics and context (“Selling point of Deadpool & Wolverine is that it doesn’t require any ‘Marvel homework,’” Hamrah notes in an entry from April 28, 2024. Similarly, this is a selling point for the forthcoming TV series Star Wars: The Acolyte, Hamrah notes on June 2).

Hamrah notes attacks on criticism itself—Jeremy O’Harris’s plea to stop engaging in “Pauline Kael cosplay” and to instead let (bad) queer cinema flourish as a form of resistance to the anti-queer federal government; the lawsuit brought by some Tamil film producers seeking to enjoin negative reviews; the argument based on Netflix’s metrics by Sony CEO Tony Vinciquerra that Madame Web was actually a fine movie, but that critics panned it for some inexplicable reason, presumably shrunken and bile-filled hearts. That is, Hamrah decries the utter misunderstanding of criticism: the failure to see negativity as a register of critical judgment, and indeed of optimistic longing for films that are better, not merely more representative or more self-contained. Better films might engage viewers in what the scholar Gayatri Chakraborty Spivak calls the “noncoercive rearrangement of desires,” a recognition of the right to demand more from art, from the economy, from life itself.

This isn’t to say that Hamrah’s metanarrative is one without stories of human agency. Indeed, the pages are teeming with wry notes of celebrities’ departures from the United States, the idiot plot that was the 2024 Democratic presidential campaign (does anyone recall, for example, when Aaron Sorkin took to the pages of The New York Times to argue that the Democratic Party should nominate Mitt Romney?), and observations about filmmakers’ baffling and insular comments on the state of the world: “True Lies director James Cameron has joined the board at Stability AI, stating he predicted how harmful AI would be when he made The Terminator in 1984, then adding ‘I warned you.”’

For Hamrah, there are also tenderly felt losses—readers follow along with Hamrah as the late director David Lynch develops emphysema, becomes unable to leave the house, and finally dies because of the pollution from the 2024 Los Angeles fires. Similarly, Hamrah recounts the tragic, lonely deaths of Betsy Arakawa by hantavirus and that of her husband, Gene Hackman, who died a week later and whose memory was ostensibly failing such that he may not have realized his wife had died. “The deaths probably occurred on February 17, according to data from the Royal Tenenbaums star’s pacemaker,” observes Hamrah: the anonymity of data from a pacemaker as opposed to the reports of friends and loved ones is stark and haunting. “Their bodies were found after a welfare check because friends, relatives, and neighbors had not seen or heard from them for some days…news media included details of the state of their corpses upon discovery.” To be sure, media focus on the grotesquerie of human decay is a sign of cultural rot, too, and an inability to pay proper respect and extend privacy to the dead who have no objecting family members to defend them. Again, Hamrah’s acidity for society’s structure emerges, though here it appears directed to the cruelty of a society without social safety nets, such that even esteemed artists can die without much notice.

There are also individual villains, those who act as little more than instruments for the working of capital: for example, David Zaslav, the head of Warner Bros. Discovery. In Zaslav, Hamrah locates the worst excesses of late capitalist/end times cinema: the elevation of “formula movies based on preexisting intellectual property” over more risky endeavors and new stories, the privileging of streaming films in one’s own home over the romantic communal experience of theater-going (already, you can hear “We come to this place for magic” in Kidman’s characteristic Australian drawl). Notes Hamrah, “When executives like Zaslav talk about the future, they are speaking from a place of greed, but also cowardice. Their release slates of sequels, prequels . . . show they are not risk takers. Their goals are to offshore and eventually eliminate labor in domestic film production.”

The elimination of the human and of the artist’s hunger for risk—not for ends that are monstrously evil to begin with, but for the utterly banal goal of producing cheaper, more reliable-if-bland media-slop—is a plotline out of virtually every science fiction movie ever made. Hamrah is never so cheap as to suggest that it is these CEOs’ failure to have watched those science fiction parables that has led them astray—but nevertheless that pat conclusion is seductive. Hamrah’s answer is rather more prosaic. In a world where critical categories have collapsed (the eponymous “end times”) or even been reviled, it becomes difficult to differentiate cultural products from each other. What appears to Hamrah and to the sliver of moviegoers who seek out difficulty, metanarrative, and layered contextual works as a flaming offshoot of the Pacific Gyre can appear to undiscerning executives and consumers as “an orchard blossoming with ripe fruit.” That is, the world that executives, financiers, and tech mavens are ushering in is one of (in the language of centrist liberals Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein) capital-A Abundance, with more media to watch and more subscriptions to pay for.

To consider the structural explanation (capitalism) alongside the human one (greed) leads to a strange double vision: on the one hand, the choices made to continue churning out roughly generated scripts on the basis of superhero comics from seventy years ago are not made by disembodied capital, rather, they must be made by individuals like Zaslav, Disney CEO Bob Iger, and their confederates. And yet, it is oddly hollow to blame them, too: that the money-making factory of the film industry would seek to continue making money and cater to the lowest common denominator of taste and complexity when it comes to cultural off-cuts can come as no surprise. That there remain on the margins of the Hollywood system, or away from the United States as a whole, films that continue to provoke, arouse, and affect speaks to the fantastic quality of a prelapsarian cinematic industry.

That is because, as Hamrah says, “the real movie news is not in the Entertainment or Arts sections anymore, but in the Business and Tech pages.” Was it ever different? It is hard to say that Hamrah is not keen to the distinctions between corporate cinema and its marginal, auteur counterparts—he is a very astute critic in longform. Rather, it’s the project’s relentless focus on the excesses of “end times cinema” that undercuts Hamrah’s ability to render on these pages the judgment that one demands of a critic. What is good and worth paying attention to is given no airtime at all—one will find in these pages only the culture industry’s dross. He calls it, after a friend’s volunteered description, a form of “hybrid criticism.” It is closer, rather, to performance art, a public vituperation. Indeed, Hamrah urges us to “turn the battleship around,” but offers nothing here in the way of a cheerier alternative to look for in the offing.

Sohum Pal (he/they) is a graduate student and critic(?) in New York City. His work appears in Full Stop, The New Inquiry, Lux, and Los Angeles Review of Books.

This post may contain affiliate links.