[Cardboard House Press; 2025]

Tr. from the Spanish by Daniel Borzutzky and Alec Schumacher

In Bodies Found in Various Places: The Selected Poems of Elvira Hernández, translators Daniel Borzutzky and Alec Schumacher bring to English-speaking audiences a curated poetry powerhouse. Hernández’s poems speak with profound resolve driven by masterful imagery. From activist documentations of Chile’s 1973-1990 military dictatorship to her observations and rhetoric on environmental concerns, these poems call out injustices with startling relevancy to our current moment.

Even in Chile, Elvira Hernández’s long-active contemporary and neo-avant garde poetry has only recently become more visible with national award recognitions, including the 2024 National Literature Prize. Born Rosa María Teresa Adriasola Olave in 1951 in Lebu, Chile, she studied under poets Enrique Lihn and Nicanor Parra at the University of Chile in Santiago. However, at the start of Pinochet’s dictatorship, due to a case of mistaken identity, she was detained and tortured at a military barracks for five days. Her first collection The Chilean Flag—a work combatting the human rights abuses the dictatorship enacted—was composed in 1981 and due to strict censorship, circulated as photocopies under a commonplace pseudonym: Elvira Hernández. It was officially published a decade later. Hernández has maintained a low profile as a poet. Borzutzky and Schumacher share in the anthology’s preface on this ethics of invisibility, marked by her belief that “the poet should observe, not be observed.” This approach manifests with Hernández’s writing rarely delving into her personal experience and instead embracing the voice of a collective. Bodies Found in Various Places: The Selected Poems of Elvira Hernández is the first collection with significant portions of six major works of her poetry written between 1981-2018 presented with parallel text alignment for the Spanish original and English translation. The sheer scope of it creates a thoughtful and comprehensive anthology sure to move new and returning audiences.

The poems themselves exercise resistance. They’re at once fearlessly satirical and heart-wrenchingly sobering in their documentation of human rights abuses. In the titular series Bodies Found in Various Places, written in 1982 and published in 2016, five poems discover the nearly unrecognizable bodies of “disappeared” political prisoners. When documenting horrific scenes, one challenge poets confront is when to employ figurative language, with some writers believing it can overstep, alter, or infringe upon the brutal realities. Hernández navigates this in the opening of the first poem “alguien sin dolor dijo era una ojerosa piedra pómez / muchos años insomne,” translated as “someone without pain said it was a hollow-eyed pumice stone / sleepless many years.” With this rhetorical gesture, she acknowledges that what follows will be filtered through a privileged lens. The metaphor becomes a way to connect to something incomprehensibly awful—a body like a pumice stone forged through the violence of a volcanic eruption. She further acknowledges the stark reality with lines devoid of punctuation or capitalization. The second poem of the series begins:

it appeared to the incredulous of the sea without abyssal eyes

brilliant in the green salt its marine sequins

like a brief eel struck down by its own lighting

starfish little octopuses algae hair

long nails like calcareous oars of life

Here the imagery that Hernández selects works on multiple levels. The body discarded in the ocean is at once what it was and what it’s becoming. She tests the stretch of an effective simile by overlapping figurative ocean imagery and literal ocean imagery: “like a brief eel.” In another poem this might risk the image falling flat. But in Hernández’s poem, it succeeds in showing how this decomposing body collapses simile. It is the ocean and itself. There isn’t actually an eel, but there are starfish and algae hair separated by blank space as if pieces set out on a tray for an autopsy. The image becomes complete in the way Ovid’s metamorphoses are fulfilled with Echo’s curse to repeat others infinitely becoming pure echo, or Arachne’s talent for weaving continuing on when she becomes a literal arachnid. Formally, these gaps in the fourth line encourage the reader to see what’s missing—both of the body and a life cut short. The eel struck by its own lightning is almost promethean, caught in a violent cycle of punishment. Hernández ends this poem with the final line: “escapado de su ancla perdida se juntó a mi lágrima tranquila,” translated as “freed from its lost anchor it joined my tranquil tear.” With this she empathizes that these bodies are no longer abandoned to silence; still, tranquility has us both in a solemn state and leaves us wondering what justice or reparations will follow.

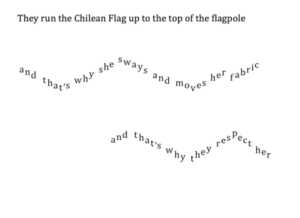

There is a kind of magic to the poems that dance along the pages with flowing indents. While the words are often painful and heavy, this is not to say the poems become unapproachable. Hernández’s insightful expression—short poems deeply invested in image and framed by swaths of blank space—add emotional levity to the heaviness of her subjects. Playful visual and formal elements further dramatize some pieces. In The Chilean Flag, her iconic work in which the flag is both a symbol forced to represent a fascist rule and a woman’s body, there are a number of experimental forms. On one page, letters recreate the wave of a flag:

With the flag already gendered as “she” and “it” in prior poems, the action of “[running] the Chilean Flag up to the top of the flagpole,” connotes a violent chase, the sway of a powerless body. On another page, “raise lower” repeats eighteen times in two columns down the page to depict the symbol’s empty performance, exhaustion, and surrender.

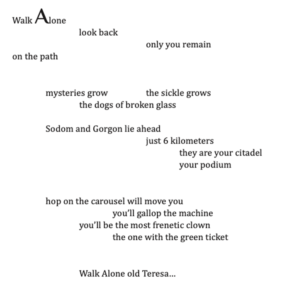

Another work explores form in an abecedarian. Grappling with the unspeakable, Hernández’s Santiago Waria, written in 1991 and published in 1992, recounts the transition of the city after the military regime. In a rare moment of personal address in the first poem for A: “Anda Sola” or “Walk Alone,” the translation reads:

This poem is particularly profound in its use of second person. Hernández achieves a collective voice as Chileans stand apart, entering their city, a city destroyed like Sodom and Gomorrah. Except, she has twisted it. It’s not Gomorrah but a gorgon—the mythic beast whose very image turns one to stone. Thus, the overthrow of the dictatorship and entry into this new period is not one of waving banners and rejoicing, but a slow crawl back to the destruction of what was once home. This loneliness belongs not only to the speaker addressing herself (Rosa María Teresa) but to all the people who’ve lost their community and their trust.

As an individual with a rudimentary knowledge of the Spanish language, it’s evident even at the small scale of titles that Borzutzky’s and Schumacher’s creative, poetic, and careful translation choices preserve the essence of the original abecedarian form. “Fuente Neptuno” becomes “From Neptune Fountain.” The speaker of this prose poem finds their way to the iconic landmark in Santiago, saying, “I’ll take your word. Bah! What are you doing here! This is worse than crossing Avenida Cardenal Caro. Or Scylla and Charybdis on dry land. The salty sea air is absent, replaced by pure ammonia.” Whether a chance meeting with a person they recognize or the Neptune statue at the fount, we hear the disbelief and distrust in this unsettling time while a new administration takes over. The double “L” digraph in Spanish represented by a poem entitled “LLanterio” still maintains its look in the translation “Tear-FaLL.” In Q for “Qué Será,” an exact replication of the familiar Spanish phrase, Hernández justifies the form: “we haven’t passed beyond the level of the alphabet / we get stuck in the mound of the short phrase / pushing the letter for all its worth.” Rebuilding has begun, but first a new language is needed to make something of the rubble.

The brilliance of Hernández’s poetic witness is in part her ability to find the downturned facet of a story and document it. With Giddy Up, Halley! Giddy Up! written and published in 1986 in the midst of great economic disparity and widespread poverty, the speaker wonders if anyone had time to watch the comet’s arrival over Chile:

They say it had the brilliance of a sun

A black-sun brilliance in the night

An incredible Central American Afro.I didn’t see it.

The speaker must work overtime, “earning and re-earning money and making / hard cash / so the world would keep existing for me.” She reminds us that stability affords us communal celebrations, the chance to be awed, while desperate survival takes that away. By the end of that first page, the comet’s spectacle becomes horrific: “They say that it was a decapitated head appearing / and never wanting to disappear.” The dichotomy of the reportage—at once a brilliant inspiring image of identity and an incessant detachment—is nothing short of shocking as it lays bare the contradictions inherent in a society under dictatorship rule. Moreover, Hernández captures the frustration of the non-viewer with this unexpected metamorphosis.

Elvira Hernández’s message propels hope too, specifically the hope that must be nurtured after Pandora’s box has been opened. In the final section of the anthology From Birds From My Window written between 2012-2016 and published in 2016, Hernández writes nature and eco-poems with haiku-like precision:

The birds quench their thirst

cool off, and see themselves

in a drop of water.We should transform ourselves

they say to each other.

Once upon a time we were dinosaurs.

This is the entirety of a translated micropoem, “In a Drop of Water.” The birds, making the most out of very little, are also a model. Hernández teases, are such imaginings comedic, foolish, or hopeful? Readers, too, might be contained in that “we.” When is it time to transform again? In other poems from this collection, she mourns the disappearance of the lapwing and dragonfly, and speculates on the adaptation of a threatened natural world. She asks us to look out our windows as well.

In addition to inspirations gleaned from visiting birds, Hernández offers her own definition of what poetry is and what it can do. In “A Vuelo de Pájaro” / “As the Crow Flies,” she writes:

Poetry has made a habit of

grabbing something by its tip

and exhausting it by the tail. To

go over things like a trail of gunpowder.Poetry is not thematic.

Poetry discusses everything at the same time.

Poetry is a box of surprises

a nested box

of Pandora

a box.You have to approach what lies ahead

like a box.

Hernández critiques poems that exhaust their subjects, and by extension decimate them with “gunpowder.” Her definition of true poetry is a poetry that is free and contains multitudes—the topography from the viewpoint of a flying bird. She refuses to chastise Pandora, as is the common temptation. Instead, she frames her curiosity positively within poetic practice. Hernández asks us to “approach what lies ahead”—the nested boxes that require one to keep opening and opening. She celebrates the poet’s resolve to find truth in discussing “everything,” to bring painful histories to light, and to be brave enough in that climactic moment to release hope instead of shutting the box closed.

It is this hope that speaks most to me in this anthology. I find it at once chilling and invigorating to read this while malfeasance in my own country abounds. As the current president and administration proliferate a culture of fear; as masked federal law enforcement patrol neighborhoods in unmarked vehicles; as detained migrants and asylum seekers are flown across the country or out of it without notice to family or lawyers; and as numerous, alleged human rights abuses take place in immigrant detention facilities, the national trauma in Hernández’s poetics of witness resonate. Her poems hit a disturbingly familiar vibration testing the limits of our composure as we witness these events at home and follow news overseas on the humanitarian crisis ongoing in Gaza. I hear Hernández’s poems in the work of immigrants’ rights organizations and the defiance of peaceful protestors. There is a Pandora’s box here that needs emptying. We too need hope.

Elvira Hernández’s experiments with form allow for quick progress through this anthology, but with such astounding imagery and wit at every turn, each page invites longer study. Hernández offers readers a poetry of survival and disturbance, but only as much as we can cup in our hands. She tasks us to observe our environments and the injustices therein. This daring anthology is the gift we need in this moment: her empowering resilience and her resolve to defy oppression. Borzutzky and Schumacher’s Bodies Found in Various Places: The Selected Poems of Elvira Hernández is a stunning and necessary new addition to translated works.

Jacqueline Balderrama is the author of Now in Color (Perugia Press, 2020) and the chapbook Nectar and Small (Finishing Line Press, 2019). She’s worked as a Virgina G. Piper faculty-in-residence at Arizona State University where she led the Thousand Languages Project and in her final year directed the national literary organization CantoMundo. She currently resides in Los Angeles, California as a writing tutor for elementary and middle grade students.

This post may contain affiliate links.