A week before Jazmina Barrera’s The Queen of Swords came in the mail, my godmother pulled my tarot cards. It wasn’t a typical thing, just a thing I resort to when the realistic doesn’t make much sense and I need something less graspable, more esoteric. The spread was a mix of creative cards and stunted growth; many wands and some pentacles and finally, the queen of swords. My godmother said there was so much blue in the cards, that blue is a color I should pay attention to, that it could speak to some kind of synchronicity happening in the world.

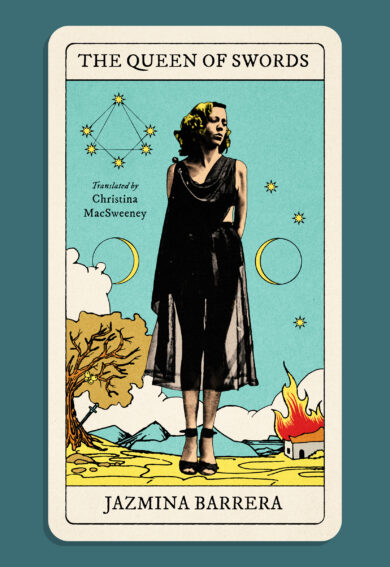

The cover of Barrera’s The Queen of Swords is blue. Elena Garro, the Mexican writer that is the subject of the book, replaces the illustration of the queen. Here was the synchronicity my godmother was talking about, clear as day, pining for me to read into it. Upon reading, I came to find out that Garro too pulled tarot cards during times of deep uncertainty, and trusted in the spiritual realm perhaps more than other realms. Barrera, in her attempt to understand Garro at a more minute level, pulled some of her own cards as well. When I asked her about this act, Barrera responded that “Garro’s life was so full of mysteries and secrets, that at some point I decided to play her own game and see what would happen if I approached her through these other paths.”

The Queen of Swords is not only a close reading into the life of Elena Garro and the short stories that she has come to be known for, it is Barrera’s personal journey into understanding an ineffable woman.

Barrera and I chatted via email. We talked about her intentions of creating an “intimate depiction” of Garro rather than a traditional biography, and how, when you let a ghost get into your skin, things can get weird.

Alia Spartz: The Queen of Swords was originally meant to be a short essay on Elena Garro, the Mexican writer. When did you realize that Garro’s story, her history, needed a much larger format than an essay?

Jazmina Barrera: When I started the research I realized that the life and work of this woman was an entire universe. Out of curiosity and instinct, I felt I needed to stay in that universe for a while.

About halfway through the book, when you are deep in your archival research, you write that despite there being “no such thing as fully understanding a living person, let alone a dead one…I go on trying to find another clue, a piece, however tiny, that turns out to be the key to doing her justice.” What do you think your role was, as a writer, in trying to represent the full life (artistic and non-artistic) of Elena Garro?

There’s a later fragment in the book where I realize how presumptuous that idea of doing her justice was. In the end I just wanted to understand her. I decided to be transparent about my process, about the information I found and my own prejudices and limitations, so that the readers could make their own mind about Elena Garro. She was such an ungraspable woman, so multifaceted too, that I didn’t want to give a univocal idea about her, I wanted to leave space for interpretation.

The book is made up of small, short chapters that are diverse in their content. Some may include diary entries made by Elena, or letters received from her husband of over twenty years, Octavio Paz, or your own personal connections to the wider work. Why did you decide on this structure for the book?

I had a portrait in mind. Not a traditional biography, but rather an intimate depiction, a dialogue with someone’s life and work. In painted portraits you can see the hand of the painter, the gestures, the point of view. All portraits are in a way self-portraits too. I wanted that to happen with this book as well. I also thought it would be interesting to try different approaches at her life. Instead of the typical chronological one, how about telling her life choosing colors as a framework? Or cats? Or numbers?

There is an early chapter where you discover that there is a tangential connection between your great-grandfather, Alfredo Barrera Vázquez, and Octavio Paz–how did discovering this connective tissue between your subject matter and your own personal life affect your writing process?

It made it more personal. It was evidence that we are all connected in the threads of history. This woman seemed so far away from me at first, and then she started to get closer and closer, not only with the finding of these coincidences, but also with the relationship I started to build with her ghost.

In a few chapters, you take the reader on your research journey with you–writing in present tense, you note down where you are running into roadblocks and you ask the other researchers in the archives who they are writing about. Why did you want to include these process moments in the book?

I just thought it was so interesting, the way we can become obsessed with a character like that. Through curiosity, research and writing, a ghost can get into your skin and then things start to get weird. The notion of identity, past and present starts to unravel.

There is a spiritualness to the connection between you and Elena Garro. You often write about the dreams you have of her, unconscious conversations that take place between you two. Do you see these dreams and unconscious conversations as a form of collaboration or guidance, and how do they shape the way you approach your own writing?

In her most difficult moments, when she was surrounded by uncertainty, Elena Garro turned to unorthodox ways of knowing, such as the tarot or the I Ching. Her life was so full of mysteries and secrets, that at some point I decided to play her own game and see what happened if I approached her through these other paths. Dreams was one of them. There, the conversations I’d been having with her ghost became autonomous (reading is always a way of talking with the dead, as Quevedo said in his poem: “I live in conversation with the dead,/ and listen with my eyes to those who died”).

When researching Garro, how did you know when to stop?

That was the hardest thing. Garro’s story is very much alive. Secrets are still being revealed, new testimonies of people who knew her keep appearing, new documents are being revealed, her books are being read in new ways all the time. I could have kept writing this book forever. But after years (willingly) trapped in her world, at some point I just knew and felt that I had given it everything I had to give.

Alia Spartz is half-Mexican and half-Italian and grew up in Atlanta, GA. She received a masters in Latin American Literature and Culture from UC Davis, and is currently an MFA candidate in Fiction at the University of San Francisco. She lives in San Francisco.

This post may contain affiliate links.