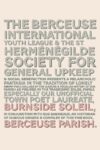

Tr. from the German by Elisabeth Lauffer

[New Vessel Press; 2025]

At the peak of my hatred, my nose obscured my vision. Like a giant herald moth perched above my top lip, it gave everything in its periphery a fuzzy quality. My eyes were constantly drawn to it, and my savings account was dedicated to its eradication.

The nose is not just cartilage and skin; it is inheritance, race, femininity, a mark of refusal, a repository of hatred and desire. Moshtari Hilal’s debut work, Ugliness, dissects what we could reductively call the beauty industry. The book’s original German title, Hässlichkeit, is derived from Hass, or hate. Over a few centuries, the hateful hässlichkeit absorbed words like disgust, and today it has ossified into a bland shorthand for “unsightly.” Translator Elisabeth Lauffer carefully preserves the layers of meaning, sustaining the word’s abrasiveness for English readers. Hilal shows how these etymological roots are still potent today: the things we call ugly are ultimately deserving of our hatred.

In five interlinking sections, Hilal takes what feels most intimate about the body and reveals its entanglement with the most public and political forces. A multidisciplinary artist and curator, she mixes poetry and essays with reams of images: drawings, school photos, advertisements, screenshots of face-warping apps, film stills. Faces peer out of the pages like a house of mirrors, and I recognize myself all too often. An essay on the origins of rhinoplasty and its seemingly more ethical sibling, ethnic rhinoplasty, evokes the hundreds of before-and-afters from private clinics in Turkey or Estonia that regularly appeared on my feed. I’m ashamed to recall the hours I lost transfixed by videos of passably attractive male surgeons holding mirrors up to women who cried with joy. I counted the months it would take to save up enough for someone to hold up a mirror to me and erase my self-hatred. Hilal acknowledges the mirror as a site of violence and asks: what do I look like to others, and what does that image cost me? Ugliness shows how we might begin, with both anger and tenderness, to look again and see what’s really there.

Hilal’s research brings us through a rich mix of influences, from Walter Mignolo and Rolando Vázquez’s critique of Kant’s Eurocentric aesthetics, through Susan Sontag and Mia Mingus on illness and disability, to Rebecca Herzig’s history of body hair removal. Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection resonates most; Hilal quotes from Powers of Horror, that it is “not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order.” Ugliness, she summarises, is not innate. It cannot be explained by measuring facial symmetry, or appealing to sanitation or vitality or even youth. It is simply “that which blurs the line between the self and the Other.”

The idea that we might find visible traces of wickedness in the face or body has roots in racist eugenics. Afghan-born Hilal explains how the long history of German antisemitism laid the foundations for excluding a wide range of Others from beauty. In Powers of Horror, Kristeva theorizes the abject as that which “does not respect borders, positions, rules.” Hilal seizes on this: body hair is abject because it blurs boundaries—between inside and outside, girlhood and womanhood, self and other. In a racialized society, it also undermines the fiction of the “pure” white body that she longed, as a child, to grow into. If for Kristeva the corpse is abject because it reminds us of death, for Hilal the Afghan nose or dense hair is also abject because it reminds German or Eurocentric society of migration, mixture, and the impossibility of racial purity. She follows these threads into the present, where in the United States facial recognition software “trained” on prison inmates pretends to objectively determine a person’s potential criminality. Misrecognition is rife, particularly if you’re not white.

Hilal questions the ubiquitous ugliness of the “evil stepmother” and the “wicked witch”: women with hooked noses, coarse hair, and angular features coded not only as unattractive but morally corrupt. I recall trying on a pointed witch’s hat, someone’s Halloween accessory, in an office job years ago—my boss exclaimed “Wow, it suits you!” before backpedalling in horror. The witch is a marker of feminine power gone “wrong” in patriarchal imagination: too visible and too disruptive. Beauty expectations are used in a kind of moral policing, Hilal argues. If you look a certain way, you are assumed to carry certain moral or social defects. Even in childhood, she found her physical features typecast:

I wasn’t cunning or cruel, but when I smiled in the mirror, I saw them there, all those mean women. They crawled from the narrow corners of my mouth, which struggled skyward like two hooks, as though I were concealing something, just like those women. I was reminded of them whenever my nose and ears rose with my smile, two horns and a beak sprouting from my face, like a crow perched on the shoulder of a European witch, like a diabolical omen. They were there with me to remind me of my role.

To look like a witch was to be assigned both excess and failure—the failure to be appropriately feminine and desirable. In a society that packages and sells youth as femininity, the nose becomes a hypervisible reminder of age, knowledge, and mortality. A baby’s nose is small, sweet, and smooth. Women who retain these dolls’ noses, with bridges that never rise and pores that never open, defy aging and stay delicate, childlike, and feminine for life. Was I ‘mature for my age’ as a girl, or did I simply have a witch’s nose?

“We fear ugliness,” writes Hilal. “We see it in the infirmity and decline of aging and sick bodies, a helplessness that threatens to rob us of our vanity, pride, and dignity. […] The frail and ailing are repellent to us, so that by distancing ourselves from them, we may forget that mortality even exists.” But we can never evade mortality for long. Ugliness accompanied me on a recent visit to Germany to see my (benevolent) step-mother, whose makeshift turquoise turban would gradually loosen over the day and inevitably slip from her bald head around dinnertime. She’d bend to retrieve it, not hurriedly but with intention, and wrap it back into place. The baldness no longer startled me—she is many months into her last dance with chemotherapy; her hair will never grow back. Hilal writes,

Ugliness is repulsive no longer

when it touches us,

comes up close

and enfolds us.

When it falls to pieces

and reaches those

we know and respect,

it robs us of any vanity

and of the power to object.

She describes the “ugliest thing of all,” the death of her mother, and how aesthetic categories clawed their way even into that.

Why do we have to save face, even in death,

adorning the ground with flowers that cost more

than all her favorite dresses put together,

dresses that got to touch

her living body.

The beauty industry for the dead can translate your “final demonstration of respect” into appropriately priced coffins and make up. “How much did you love your mother?” Your answer will help narrow down your options. The embalmer, should you opt for an open casket, can enliven the body and reverse the ravaging effects of illness; they can hide a naked head in a wig to disguise what they lost to disease; of course, if the deceased had too much hair, you can ensure their legs and armpits are as smooth as a newborn’s. All this comes at a cost—a price we pay so we “won’t have to stare death in the face.”

If ugly means being old, ill, and unloved, it’s not really that

we hate the ugly; it’s that we fear our own mortality,

fragility, and loneliness.

In the end, it is not just our own mortality we fear, but our loved ones’. “There is nothing ugly about the sight of a beloved person losing their body to illness,” Hilal summarizes.

“I think beauty is just love,” someone tells me during my visit. That is, neither beauty nor ugliness exist in the object but, as that stale adage goes, in the beholder’s eye. Still, the pursuit of beauty and flight from ugliness keep us occupied from birth until death. Love, Hilal suggests, is the precondition for beauty, just as hatred is the precondition for ugliness.

The ugly don’t exist because they are ugly, but because they endure ugliness. In this case, ugliness is the hate-based exclusion found in the judgment and behaviors of others. […] It can mean a rejection of the self as readily as that of the Other, but either way, the act is connected to the repudiation of deviance, variation, and perceived indolence—a rejection of anything that does not feed (or that disturbs) the growth and order of modern society.

Hilal refuses the conciliatory idea that ‘we’re all beautiful.’ To claim beauty for oneself is to maintain the exclusion of the ugly. Tracing its genealogy from Darwinism and colonialism to the modern beauty industry, she reveals ugliness as a powerful tool of division. She centers those always excluded by prevailing beauty norms—not just those who feel ugly sometimes, but people whose bodies are never fully recognized as acceptable, or even human. Through constant recourse to her own embodied experience, Hilal politicizes abjection without ever losing sight of its red-hot existential sting. She reimagines the abject body not as something to disavow, nor to reclaim as beautiful, but as a site of critique and creation—insisting that what is marked “ugly” or “unassimilable” might instead become visible on its own terms.

In the shadow of my nose is a place

where difference is free

to eclipse conformity;

where the I in place of nothing,

will have uncovered

our gaze and yours.

Hannah Weber is a German-Canadian writer and critic. She has published work in World Literature Today, Words Without Borders, and Asymptote, among others. She lives on the south coast of England.

This post may contain affiliate links.