This essay was first published last month in our subscriber-only newsletter. To receive the monthly newsletter and to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider joining us on Patreon.

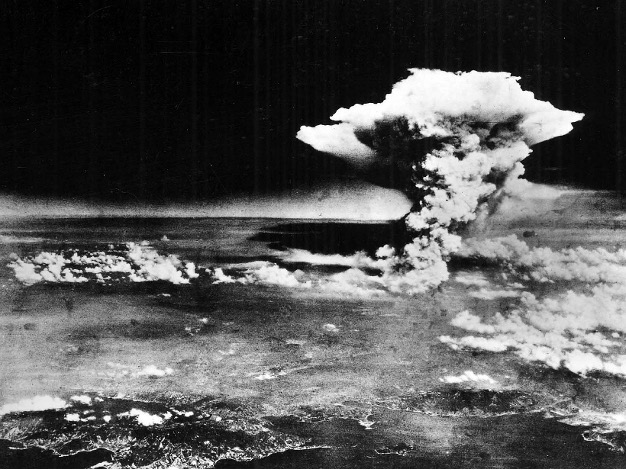

The Mk I bomb, nicknamed “Little Boy,” was the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. It was delivered by the B-29 Enola Gay … it detonated at an altitude of 1,800 feet over Hiroshima, Japan, on Aug. 6, 1945. . . . “Little Boy” was a gun-type weapon, which detonated by firing one mass of uranium down a cylinder into another mass to create a self-sustaining nuclear reaction. Weighing about 9,000 pounds, it produced an explosive force equal to 20,000 tons of TNT.

National Museum of the United States Air Force (2025)

*

Hit myght laste til Domesday.

R. Mannyng, Chronicle Wace (1330)

*

I.

In China, 142 AD, the “Father of Alchemy” Wei Boyang writes the Cantong qi, otherwise known as Kinship of the Three, a Taoist text on alchemy. In it, he describes a mixture of three powders that “fly and dance” violently.

Ninth century AD, Chinese alchemists searching for an elixir of life stumble across sodium and potassium nitrate. A Taoist text warns against an assortment of dangerous formulas:

Some have heated together sulfur, arsenic disulfide, and saltpeter with honey; smoke and flames result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house burned down.

Fifteen years ago in Halifax, Nova Scotia, I used to meet up with my friend Nate Crawford to talk about the apocalypse. We sat at a picnic table in his backyard every Friday and wondered how the world would end.

We were both fascinated by the Halifax Explosion. On December 6, 1917, at 9:04:35 a.m., the French cargo ship SS Mont-Blanc collided with the Norwegian ship SS Imo in Halifax harbor. The Mont-Blanc, filled with munitions, caught fire, exploded. Biggest explosion before Hiroshima.

Nate knew more than me about the history of the bomb. He explained how in 1939 physicists figured out that if atoms of a particular isotope of uranium are bombarded with neutrons, they split, releasing energy in a chain reaction. He told me about the Manhattan Project, scientists gathering in the New Mexico desert to build the first atomic bomb.

We knowen hym wel, that lytel boye.

I was more fascinated by the artwork that came as a response to World War II: the Existentialists, Abstract Expressionists, Pop Art, Jazz, Theater of the Absurd.

Lytel boye weigheth nyne thousande poundes,

Ys eyghte and twenti ynches wyde:

An hundred and fourti poundes of enrichèd uranyum

Withinne his wombe.

I read Nate my poems about the Halifax explosion: overly indebted, it’s clear, to Williams’s Paterson:

from under the water i hear a whistle blast,

the sun blinks,

9am,

i lift my head, crammed with picric acid, from the water,

the air’s crisp, there’s no snow.

Our conversations meandered into zombies, comic books, climate change, and the nature of evil.

I explained to Nate that I don’t believe in evil. I am, in my heart, a hippy who believes everyone—even the worst of us—has the capacity for renewal. For me the question of evil should be reframed as psychological, not religious. Pure evil only exists in horror movies and comic books.

It helpeth to see Lytel Boye as a lytel boye. Humayn.

A boye as ich was:

Rounde visage, shorte breches, sneekers.

As thow mighte seen in 1945.

The Cold War, for those of us growing up in the 1970s, was our constant threat of catastrophic violence. The idea of weapons of mass destruction always in the air. Because of Hiroshima, we all knew that kind of violence was possible. This was no comic book: Galactus, world-eater. This had happened to real people.

II.

What happens when cruel machinery evolves for thousands of years? What if the makers of that machinery are filled with spiritual longing?

The epic poem Orlando furioso, by Ludovico Ariosto (1474–1533), describes a weapon of mass destruction with the power to destroy a city: l’archebugio, the arquebus. The poem takes place in sixth century AD: a universe of chivalry, paladins, damsels, magicians, devils.

Cimosco, the weak, treacherous, autocratic king of Frisia, challenges the great warrior Orlando: a Gilgamesh-like hero full of ego and swagger. Cimosco’s ace in the hole: the arquebus. This long gun, like a blunderbuss, was used from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries. Unreliable, but with explosive kinetic energy. Much superior to the previous alpha weapon, the longbow.

Lytel boye sitteth in a sande-box withinne a cité parke,

Pleyinge aloon.

Ariosto—by referring to a weapon from his time which had no place in the world of the heroic paladins—alludes to the Italian Wars he was experiencing in his beloved hometown, Ferrara. In 1494, French King Charles VIII descended into Italy at the head of a large army. This war continued for sixty years. Ariosto forces us readers to assimilate now (sixteenth century, Ariosto’s time, rife with violence, blood, cannons, gunpowder, death) and then (the romanticized epoch of Charlemagne’s paladins).

The arquebus is a powerful symbol of now. Its very existence suggests that Orlando’s world, and the age of chivalry, would end.

I sitte upon the hem of the sande-box.

“Well met,” quoth I.

But lytel boye loketh not upon me.

Cimosco whips out his “abominable device,” which Orlando has never seen, and fires it at him. He misses. A violent cacophony—“The fiery arrow, which breaks and faints / . . . gives no pardon, / hisses and screeches”—that sounds, alliteratively, like bullets whizzing by. War in language itself.

Orlando stabs Cimosco, killing him with ease. But just before that, Ariosto slips in two stanzas referring to the terrifying power of war instruments of now: “Whoever saw the fire fall from heaven / which Jupiter unleashes with such a horrendous sound, / and penetrate where a closed place / carbon with sulfur and saltpeter . . .” This “horrendous sound” is not just the arquebus, but cannons “which seem to light up the sky, rather than the earth; / breaking walls, uprooting the heavy walls, / making the stones fly up to the stars.”

I axe the lytel boye, “Where is thy mooder?”

He loketh stedefastly on me,

hys eyen al whyte, no pupilles therein.

Cimosco doesn’t respect the paladins’ simple tools—sword, helmet, shield, armor—that adhere to the human form. Cannons demolish bodies without thought, pride, honor.

After Cimosco is gone, Orlando tosses the arquebus off a bridge into the ocean deep. There the cruel technology will be safe . . . as long as nobody ever finds it.

*

Nate explained that it took the Manhattan Project scientists seven years to develop an atomic bomb. They set it off on July 16, 1945, at Los Alamos.

That A-bomb was called Trinity after John Donne’s poem “Batter My Heart, Three Person’d God,” whose speaker, unable to allow God into himself, implores God to forcefully break and remake him. The paradox: Only through violent divine intervention can the speaker be free of sin.

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

It would be tempting, if you were a theoretical physicist working on the first atomic bomb, to imagine yourself as a demiurge. To frame the process as spiritual longing for God’s wrath—breaking, blowing, burning—to “make [yourself] new.” The Los Alamos director, Oppenheimer, had the idea that perhaps this weapon of death could end war and save humankind.

Such grandiose ideas dissolved quickly in the reality of the war. Three weeks after Trinity was set off, the Allies were desperate to overpower Japan and end World War II, so US President Harry S. Truman ordered a uranium bomb dropped on Japan. On the morning of August 6, 1945—8:16:02 a.m. local time—the American B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped the world’s first A-bomb, called “Little Boy,” on the city of Hiroshima.

Three days later, August 9, the US dropped another A-bomb, called “Fat Man,” on the city of Nagasaki.

III.

On a retreat in the Adirondacks in 2024, I find a copy John Hershey’s Hiroshima on the bookshelf of my cabin. Interviews with people from Hiroshima describing the morning of August 6, 1945:

Opposite the house, to the right of the front door, there was a large, finicky rock garden. There was no sound of planes. The morning was still; the place was cool and pleasant.

Japanese people didn’t use the phrase “Original Child Bomb”: It originated in Hershey’s Hiroshima book as a “creative translation” of the Japanese word for atomic bomb: 原子爆弾.

Then a tremendous flash of light cut across the sky.

Nonetheless, Thomas Merton called his poem about Hiroshima Original Child Bomb. Merton—who did not speak fluent Japanese but was interested in Zen and Suzuki Roshi—titled his poem on a loose translation of the words Genshi (“atom”) and bakudan (“bomb”) in an attempt to comment on the bomb’s almost mythic status as firstborn in the lineage of weapons of mass destruction.

Under what seemed to be a local dust cloud, the day grew darker and darker.

Since 1945, of course, the Japanese have grappled with what was done to them. Japanese activists have protested against nuclear weapons and for the spread of accurate information. The 2024 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Nihon Hidankyo (the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers) for their activism against nuclear weapons, assisted by survivors (known as Hibakusha, 被爆者) of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

She had taken a single step (the house was 1,350 yards, or three-quarters of a mile, from the center of the explosion) when something picked her up and she seemed to fly into the next room over the raised sleeping platform, pursued by parts of her house.

The dance form Butoh (舞踏, Butō) was developed by Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno in the late 1950s: an avant-garde response to the collective trauma of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It’s achingly beautiful, performed in white body makeup with slow hyper-acute contortions.

It seemed a sheet of sun.

Many Japanese films have also dealt with the traumatic legacy of the bombs: Hiroshima (dir. Hideo Sekigawa, 1953), Record of Living Things (dir. Akira Kurosawa, 1955), House (dir. Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977), Black Rain (dir. Shohei Imamura, 1989), In This Corner of the World (dir. Sunao Katabuchi, 2016), and others.

Now the lytel boye maketh hymself as the harmèd childe,

Accusynge the cité-folke,

And lyk a wratheful cherubin felled them.

The first Godzilla (1954) film, directed by Ishirō Honda, is about a monster knocked out of his deep-sea habitat by H-bomb testing. Godzilla, a 165-foot tall, 20,000-ton dinosaur, a reptilian kaiju (“large monster”) version of the H-bomb, seething with radiation.

The film uses the allegory of a monster attacking Tokyo to help Japanese people process the trauma of the Hiroshima bombing.

He was one step beyond an open window when the light of the bomb was reflected, like a giant photographic flash, in the corridor. He ducked down on one knee and said to himself, as only a Japanese would, “Sasaki, gambare! Be brave!”

A woman on a bus jokes: “It’s awful! Atomic tuna, radioactive fallout, and now this Godzilla to top it off! What if it shows up in Tokyo Bay?” A man replies, “It’ll probably go for you first.” She says, “You’re horrible! I barely escaped the atomic bomb in Nagasaki—and now this!”

He pisseth on the sande in a wyde arc,

And drenchèd he the folke of the cité.

Godzilla: monster-likeness of the H-bomb, atomic breath, destructive capability of a nuclear blast. Stuntman Haruo Nakajima, rampaging Tokyo in his Godzilla suit, moves slowly, eerily, Butoh-like. An underwater nightmare.

Honda’s montage of Tokyo destroyed by Godzilla calls to mind the photos of Hiroshima taken on August 7, 1945.

The film’s narrative centers on a family: the father, Kyohei, a paleontologist; his kind daughter, Emiko; the daughter’s fiancé, Hideto. The government asks Kyohei how to kill Godzilla. Kyohei refuses to comply, pleading with them to study Godzilla and not resort to violence. It’s an anti-violent monster movie. (The American version—called Godzilla, King of the Monsters, with footage of Raymond Burr, who wasn’t in the original film, awkwardly edited into the Japanese scenes—omits much of the film’s anti-nuclear message.)

Takashi Shimura, who played Kyohei, was well known in Japan: in over two hundred films, including thirty by Kurosawa. Shimura’s constant expression in Godzilla is incredulity at the terrifying stupidity of the people around him: reminiscent of Anthony Fauci, the American immunologist who—at press conferences during the Covid pandemic, attacked by pundits with a political axe to grind—often had a similar look of incredulous restraint and surprise.

Just as she turned her head away from the windows, the room was filled with a blinding light. She was paralyzed by fear, fixed still in her chair for a long moment (the plant was 1600 yards from the center).

A rival scientist, Dr. Serizawa, invents a machine to kill Godzilla: the oxygen destroyer. But he’s reluctant to hand it over because, he says, “If the oxygen destroyer is used even once, the politicians of the world won’t stand idly by. They’ll inevitably turn it into a weapon. A-bombs against A-bombs, H-bombs against H-bombs. As a scientist, no as a human being, adding another weapon to humanity’s arsenal is something I can’t allow.” Hear, hear!

Anon lytel boye casteth adoun the cité,

And danceth he upon it.

The myst aboute his lytel legges semeth lyk the margyne of the see.

Serizawa allows the government to use his deadly device on two conditions: 1) that he destroys his notes on it; and 2) that he lets himself drown when the monster is killed. That way, the secret of this terrible weapon will die with him.

Godzilla asks perhaps the most important question of the Anthropocene era: Who regulates the technology that we invent? The subsequent thirty-plus Godzilla films all lose the urgency of the first. A monster disconnected from its cultural relevance is just a disembodied nightmare.

*

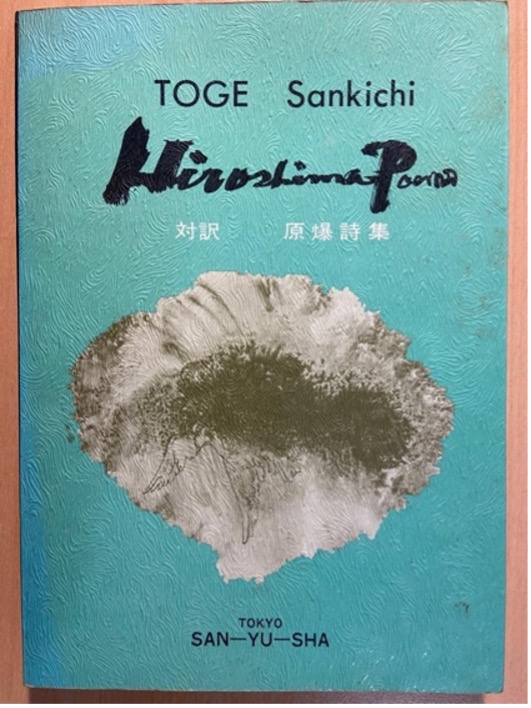

In Poems of the Atomic Bomb (1951), Tōge Sankichi attempts to stare into the abyss of the blast. He sees Japanese bodies, infinite suffering. Unlike Honda, Sankichi is more interested in the trauma of the body than in allegory.

Sankichi, who’d been a haiku poet, was twenty-eight when the bomb dropped:

On the morning of August 6, 1945, at home in a part of town more than three kilometers from Ground Zero, I was just about to set out for downtown Hiroshima when the bomb fell, and I survived merely with cuts from splinters of glass and atomic bomb sickness.

Poems of the Atomic Bomb focuses on the lives, suffering, and death of ordinary people, including graphic depictions of bodies—burned, scarred, smashed—to convey the human cost.

In the feces and urine on the floor of the arsenal

a group of schoolgirls who had fled lay fallen;

bellies swollen like drums, blinded in one eye,

skin half-gone, hairless, impossible to tell

one from the other

The book is a relentless recounting of bodies in pain. A widow who lost her son, daughter-in-law, and grandson, muttering to herself. Schoolgirls lying in agony, suffering burns and swelling. Mrs. K., a woman with severe burns and infection in a makeshift aid station. A girl with twisted hands selling tickets. A child with a neck full of glass splinters. An infant abandoned, starving.

Both allegory like Godzilla and literal description like Sankichi’s poems are, I think, effective ways to approach the unspeakable trauma of Hiroshima. In Sankichi one feels the urgency of personal memory. It makes sense that he, who’d been through the suffering of Hiroshima firsthand, would not want the details to be lost in artifice. Sankichi does not allow the bomb to become an idea, a concept. He reminds us, crucially, of bodies. Not symbol or statistics: people.

The stillness that reigned over the city of 300,000:

who can forget it?

In that hush

the white eyes of dead women and childrensent us

a soul-rending appeal:who can forget it?

But what stillness? Those closest to the blast reported a kind of silence. But others a few miles away described thunderous noise.

There was, apparently, silence just before the bomb dropped. Fifty-three seconds elapsed from the moment the bomb left the forward bomb bay until impact.

Lytel boye maketh a tre of sande,

A tre of wondre y-wrought,

That groweth in the cité.

Enola Gay pilot Paul Tibbets lurched the plane upwards in a high angle maneuver to get far away from the explosion. Bright flash. Only after lifting 11.5 miles, minutes later, did the bomber shudder with the shock waves of the blast.

Thomas Merton’s long prose poem, Original Child Bomb, in forty-one parts, attempts to describe Hiroshima from the ground:

The bomb exploded within 100 feet of the aiming point. The fireball was 18,000 feet across. The temperature at the center of the fireball was 100,000,000 degrees. The people who were near the center became nothing. The whole city was blown to bits and the ruins all caught fire instantly everywhere, burning briskly. 70,000 people were killed right away or died within a few hours. Those who did not die right away suffered great pain. Few of them were soldiers.

Actually, about 0.2 seconds after the detonation over Hiroshima the fireball that had been created reached a surface temperature of 7,700 degrees Celsius. That’s hotter than the surface of the sun, which is 5,600 Celsius.

It nys no tre. Lo, a mushrum.

Over the radio intercom co-pilot Robert Lewis: “My God, what have we done?”

IV.

Once, while teaching at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, I showed a small poetry seminar class the first fifteen minutes of the French film Hiroshima mon amour (dir. Alain Resnais, 1959): an unforgettable juxtaposition between two lovers in bed and newsreel-style images of the after-effects of the Hiroshima bombing. An operatic, trance-like opening.

I didn’t provide context, but suggested they use it as a writing prompt. After watching, one student said that they couldn’t use the prompt because Hiroshima wasn’t their story to write about.

Fair enough. It’s frightening to think about, and hard to know what our place can be in such a story. Certainly, for example, we shouldn’t appropriate those voices. We should listen.

A day ful strange and fayr,

The cloudes at gloaming as hertes a-boundynge.

But shall we also not talk or write—or even think—about it? After all, Hiroshima changed the world. Hiroshima happened to the world. Other countries, all of us, had to grapple with this terrible “original child.”

they saw that the whole community on the opposite side of the river was a sheet of fire

My student was right, though, that the film is a kind of appropriation: The French filmmakers equate their wartime experience—a drawn-out national humiliation of military defeat, occupation, and internal division—with the arguably more horrific instantaneous obliteration of a city. That equation, as we watch the film seventy years later, can feel uncomfortable at times.

Resnais and screenwriter Marguerite Duras, in Hiroshima mon amour, use Hiroshima, the city and the bomb, to address inherited trauma. Specifically, the trauma France suffered in World War II.

The first scene dissolves, in black and white, between the lovers—a Japanese man, a French woman—without providing names or showing faces. Just interiority, thought, memory. No spatiotemporal direction.

SHE: The hospital, for instance, I saw it. I’m sure I did. There is a hospital in Hiroshima.

How could I help seeing it?

HE: You did not see the hospital in Hiroshima. You saw nothing in Hiroshima.

The lovers covered with snow or ashes. Then they’re coated in sweat. In the first montage, the lovers blend—male/female, Japanese/French—with each other and with the bodies of the bomb victims.

Lytel boye doth hover a fewe inches aboven the sande,

And aboven the mushrum.

The woman steps out of bed onto the terrace of her hotel (called New Hiroshima) in a kimono. Finally, real air, fresh air. We learn about the lovers: They just met, they’re both married, it’s her last day in Hiroshima.

The film drifts with a Slow-Cinema pace in deliberate, mannered episodes: She walks away from him, he follows, they talk. Over drinks in a bar called The Tea Room, she reveals her secret story.

During World War II in Nevers, France, she took a German lover. They’d meet at the edge of town. When the romance is discovered after the war, she’s humiliated: Her hair cut short, she’s condemned and vilified by the townsfolk, banished by her own parents. In The Tea Room she relives this pain. No diegetic sounds, just her voice: We’re in France, with her. Close-ups on her face convey that her humiliation is immediate, now, now. Resnais and Duras, using visual framing, link her trauma to that of the Hiroshima victims: her in bed suffering at Nevers, like the firebomb victims; her hands bloody from scraping against a wall, like radiation sores; her shorn head, as if from radiation poisoning. Although striking, these visual parallels—making the French/Hiroshima metaphor literal—feel somewhat heavy-handed.

On some undressed bodies, the burns had made patterns—of undershirt straps and suspenders and, on the skin of some women (since white repelled the heat from the bomb and dark clothes absorbed it and conducted it to the skin), the shapes of flowers they had had on their kimonos.

In Duras’s script, the lovers speak contradictions, their minds contorting to conceive of the terrible reality around them. “You’re destroying me, you’re good for me,” she says three times.

In the interior, timeless space of the woman, the Japanese lover melts into the German lover.

At a beautiful moon bridge, he passed a naked, living woman who seemed to have been burned from head to toe and was red all over.

Finally at the end the lovers call each other by their true names: She calls him Hiroshima; he calls her Nevers. So Resnais and Duras, by portraying the lovers as symbols, keep their distance from the deepest Japanese horrors of the body: That was Sankichi’s story to tell, not theirs.

When Resnais and Duras—French citizens who’d lived through World War II—looked into the darkness of Hiroshima, they saw themselves: French humiliation, French trauma, French complicity. They saw their inherited historical pain, which is also personal.

*

Nate and I were both obsessed with David Lynch. Our conversations ranged from Dune (1984), that space-operatic sci-fi dystopia failure (it’s also mesmerizing and beautiful); to the sheriff of Twin Peaks (1990–91, 2017) whose name is Harry S. Truman. Lynch—who’d been a kid in the 1950s, height of the Cold War—is obsessed with the A-bomb. In Eraserhead (1977), in a small frame on the wall beside Henry’s bed, where one usually places a portrait of a loved one, is a picture of a mushroom cloud. In Twin Peaks: The Return (2017), there’s another photo of an atomic explosion on the office wall of Gordon Cole, Lynch’s FBI alter ego.

The Return arrived ten years after my talks with Nate. We couldn’t have guessed how much the new season would focus on the atom bomb, Hiroshima, and the birth of evil.

About a week after the bomb dropped, a vague, incomprehensible rumor reached Hiroshima—that the city had been destroyed by the energy released when atoms were somehow split in two. The weapon was referred to in this word-of-mouth report as genshi bakudan—the root characters of which can be translated as “original child bomb.”

Episode eight begins with special agent Dale Cooper’s evil twin driving on the night road with Ray. They get out of the car, argue; Ray shoots evil Cooper, drives off. Out of the dark forest ghostly hobos, “Woodsmen,” appear and revive evil Cooper by “removing” BOB, a figure of evil. Cut to the Roadhouse: Nine Inch Nails performs an entire song, “She’s Gone Away.”

Lytel boye draweth out Pole-a-roid likenesses

From out hys pockets,

Scattereth o’er the sande.

Then—à la Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life, which pauses for twenty minutes mid-film to recount the evolutionary story of the universe—comes the most electrifying minutes Lynch has ever put on screen.

TITLE CARD: “July 16, 1945.”

In the distance, Trinity. Cosmic wide-angle lens. Mushroom cloud, desert. The camera drifts—impossibly, calmly, dangerously—closer, closer, finally entering the cloud. CGI was invented for this.

We enter the bomb itself: flashes, sparks, flickering, static. A new space, cf. Eraserhead radiator, cf. the Red Room with its zig-zag floor. Bomb-consciousness.

Cacophonic music, louder, louder. Krzysztof Penderecki’s 1961 composition for fifty-two strings, “Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima.” If human suffering could be music.

Establishing Shot, stationary camera. A burnt-out convenience store, 1950s: The Woodsmen, ghostly hobos, walk in and out, flashing with light. Low angle shot: A humanoid form (called “The Experiment,” Eric Eynon) spews primordial sperm, a long intestine of guts or smoke. A face emerges, it’s BOB, evil, senseless evil, evil for the sake of evil. Fire personified. Born of the bombing.

A long aerial shot—again beautiful CGI—skimming over an ocean, a gaseous ocean, fast, toward an island, craggy rocks, upward, upward, a smooth modern castle at the top. We enter slow—threshold crossed—into a window. It’s perhaps the 1930s, a record playing too slowly. A woman, Senorita Dido, dressed as a flapper, weaves to and fro on the couch. An alarm rings, the Twin Peaks giant in a tux steps out from behind a black bell. He watches a screen depicting the bomb and BOB; then he, the giant, levitates into the air with a golden cosmic river pouring out of his mouth. Senorita Dido steps over to examine a ball of gold the giant disgorged. Laura Palmer’s face appears in the gold orb, and Senorita Dido—bringing Glinda the Good Witch vibes—kisses her.

Eleven years later, New Mexico desert. Out of an egg in the sand, a bloody insect, a frog-moth, crawls. Teenage lovers walk, chatting, finding a penny. Out of the dark the Woodsmen frighten drivers passing by—“Got a light! Got a light!”—and converge on a radio station, murdering all.

A gentlewoman goeth by,

Lytel boye showeth hir hys middel fynger.

A Woodsman repeats these words into the radio mic:

This is the water and this is the well. Drink full and descend. The horse is the white of the eyes and dark within . . .

All those who hear the broadcast faint. The frog-moth that came out of the egg crawls into the teenage girl’s mouth.

Like Resnais and Duras, Lynch has personalized Hiroshima. In his vision, Hiroshima becomes the mythic origin of BOB, the evil spirit that terrorized Laura Palmer. Hiroshima a fissure in existence, radiating terror and terrible creation.

Perhaps no one has the right to speak for the Japanese people on the subject of Hiroshima. Yet the effects of the bomb, the “original child” of our nuclear aspirations, have been felt by people all around the world. I appreciate how the event has been refracted into such a spectrum of representations: allegory, metaphor, avant-garde film, newsreel footage, dance, music, and grueling reportage. To me, these artists are sincerely trying to grapple with a shared human horror, which is one of the essential roles of art.

V.

“This bullet is an old one,” says Borges, referring to JFK’s death. It’s the same exact bullet that killed Lincoln, Caesar, Christ. It might have also been the rock that Cain hurled at Abel.

In the morning, I was eating peanuts. I saw a light. I was knocked to little sister’s sleeping place . . . The neighbors were walking around burned and bleeding. Hataya-san told me to run away with her. I said I wanted to wait for my mother. We went to the park. A whirlwind came. At night a gas tank burned and I saw the reflection in the river.

The bullet a manifestation of power, the form power takes in the world. The rock and bullet and arquebus and oxygen destroyer. The sulfur and arsenic disulfide and saltpeter with honey.

Hölderlin says, “But where the danger is, also grows the saving power.” But, Shakespeare asks, what if it doesn’t? Macbeth, as he plans to kill Duncan, knows how empty ambition is: “I have no spur / To prick the sides of my intent, but only / Vaulting ambition, which o’erleaps itself / And falls on the other—” He knows he’s stepping into the dark, but can’t help himself.

Later, when his wife Lady Macbeth has gone mad, and he himself descends into paranoic isolation and tyranny, he speak to the nihilism and senselessness and abyss:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death.

Spoken like a suicide. That’s when it hits me, how I’ve participated in the “dusty death” of those around me, damaging their “saving power.”

And lo, ich beholde

There was a brown-haired girl with brown eyes who loved me more than I loved her. I pulled away and didn’t tell her, kept on seeing her. In September she broke her leg on her bike. I didn’t visit the hospital, didn’t call, and started seeing another woman.

To myn eye, that lytel boye hath

A bowle of russed heer, and frekeles withal,

And for his eyen, shene and clere,

Oon of my mooder is,

Thilke oother my fader’s, trewely.

One night in October we planned to go to a movie. On the way I told her I was with somebody else. She sat on the curb and cried.

I lay myn hand upon his bak, softe,

And he doth

Squezen the sande,

Bitwixen his fyngres.

*

It’s like a bad dream Harry S. Truman had. There he was in front of an abandoned church. Why was it abandoned? Harry S. Truman didn’t know, so he knocked.

His knock a question.

The answer Harry S. Truman received: an abyss of bright light.

An abyss, Harry S. Truman thought, because bottomless, topless, sides-less. Like his love for Bess. That made sense.

Wait, what question did he ask to receive this bottomless answer? He couldn’t remember.

How lonely, said Bess (still in Harry S. Truman’s bad dream), Hiroshima must be, by itself over there across the sea.

Harry S. Truman replied, When Dante saw Hiroshima it was at the core of the earth, it was Lucifer’s body.

Well, it’s not at the core of the earth no more, said Bess. Now it’s out and lonesome, said Bess.

Harry S. Truman repeated, Now it’s out and lonesome.

But no words came out of Harry S. Truman. Just a kind of silence.

John Wall Barger is the author of six collections of poems and one critical collection. His next book of poems, Resurrection Pie, is forthcoming with LSU Press in 2026. He’s a contract editor for Frontenac House, lives in Vermont, and lectures in the Writing Program at Dartmouth College.

This post may contain affiliate links.