Madeline McDonnell is the author of the debut novel, Lonesome Ballroom, just out from Rescue Press. She has written two previous collections of fiction and lives in Oregon.

Lonesome Ballroom is an inquiry into gender’s relationship to popular aesthetics, swirling from ancient epics to turn-of-the-millennium reality shows, mid-century melodramas to neo-noir car chases, beauteous battle scenes to boy-next-door meet-cutes. It’s a rambunctious performance in prose. Edan Leupuki says Lonesome Ballroom “dazzled and deranged”; Leni Zumas wrote that Lonesome Ballroom is a “magnificent dive into film, fashion, [and] feminism”; and Sarah Shun-lien Bynum calls McDonnell a “fearless and soulful original.”

I spoke with McDonnell in spring 2025 about her quest to write an anti-epic epic, her sonic sensibility, and her approach to research.

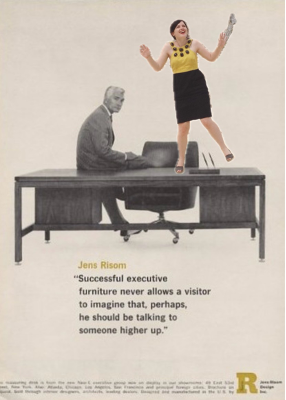

Miles Mikofsky: I want to start off by saying: I hadn’t known I’d been sitting on the Danish designer Jens Risom for years before reading Lonesome Ballroom. His midcentury tables are a favorite obsession of your protagonist Betty, and his chairs furnish my favorite bookstore, the Seminary Co-op (have you been?).

I made the connection while perusing the “research trips!” tab on your website, a works consulted with links to such captivations as: Old Yeller rabies scene; Judith Butler’s Instagram; the official rules of beer pong; footage of “Putricia” (Sydney, Australia’s celebrity corpse flower); Emily Wilson doing costumed dramatic readings from The Odyssey; and many, many, classic films. Could you talk about the role of the research—cultural, cinematic, comedic, etc.—in your novel?

Madeline McDonnell: I started Lonesome Ballroom after moving to Seattle so that my boyfriend could write a novel about a fishing village. Did I accompany him on “research trips” to the docks and the locks? Yes! Was I abashed that the life we were making didn’t revolve around my “research”? Sure! Did I assuage my shame by sitting at our kitchen table mainlining The Hills—which was doing this new thing called “streaming,” its poisons requiring little but a laptop? Yep! My face floated atop Lauren Conrad’s, our dead eyes fused… But wait! My eyes were re-animating, alive with sudden pleasure… I loved the wack disjunction between the aggressive dunh-dunh-dunhs of that show’s score/voiceover and its conflict-averse scenes. It took a decade to realize that this too was research, into the clashing cultural scripts women inherit.

In her great book How Should a Person Be?, Sheila Heti locates a reality TV heiress giving a handjob within a tradition of “warriors down through time…who…just kept their wrists steady and struck,” and I mean the label “Research Trips!” the way I read that line: you’re supposed to laugh, but it’s serious, too.

As for the Seminary Co-op, I’ve only been via YouTube, but how nice to see those red-bird Risom 650s aflutter in the windows! Our mutual friend Jens came my way like LC—because I was a person who sits in chairs, at tables. I’d moved. I needed furniture. But why did I long for the objects in an image like this even as I felt oppressed by its message? The tension between my attraction to the retro and abhorrence of the retrograde spoke to contradictions I was exploring in Lonesome Ballroom.

Betty’s not just a protagonist, she’s the protagonist-narrator of her own “movie musical in prose cry for help debut novel.” She moves in smash-cuts, close-ups, and fade-outs. She speaks in crossed-out lines (see above) and great gossipy gushes of doomed doggerel. More than once it felt trapping, especially without the artifice of escape to a narrator-in-the-sky. How did you first find or hear Betty’s character?

Trapping indeed!—ugh, I would often think when I was first writing, why does Betty’s voice keep coming out like, ugh², this!?—its adornments were annoying, its enclosure an obstacle to interesting material. But your choice of the word “hear” feels accurate even if I can’t quite explain the “how.” And with little else to go on (I had no idea what the book was “about” yet!) I followed the sonic logic I’d found…

Speaking of “following,” it’s a (true!) truism that form and style should “follow content.” What working on Lonesome Ballroom revealed to me, however, is that the facile follower, style, might also reveal subconscious content. And how cool to think that by attending to the implications of an instinctive sound, a writer might find a hiding subject… Which is all to say: years into working on Lonesome Ballroom I realized that the entrapping vocal trappings I’d rued had been enacting the entrapping trappings I’d been writing about all along! I began seeing the prose as a sort of sequined dress—the fetching, intrusive language expressing Betty’s love-hate of feminine practices, their terrific thrill and terrible thrall. By the end, I was leaning into a lyrical glitter that abrades and invites, as well as recursion within sentences and paragraphs, going so far as to add rhymes and whirl-twirl-swirls, as heretic as this might sound to some!

Trying to describe Betty, I found myself saying the word “womanchild,” then wondering why no one says that when plenty of us say “manchild,” then realizing “manchild” would make a distinction “womanchild” didn’t if the idea of dependence was already inside our idea of a woman. Then I considered calling Betty an “antiheroine” in contrast to the past couple decades of masculine “antiheroes” we all know from, like, HBO. Could you talk about your interest in passivity, and in action?

Hmm, well maybe I should cut back to, ugh³, late-aughts Seattle, where I wrote in a room that was separated from my fishing-novel boyfriend’s by a wall. Can I blame his proximity for the dysfunctional draft I produced there—for the fact that the character of Goodman, now a table-bound chatterbox, was first a Dantean Virgil-mystic figure guiding Betty into hellish and explosive scenes? Was it my then-bf-now-spouse’s fault that pages passed on WWII battlefields!? That Betty became pseudo-involved with a P.G. Wodehouse superfan possessing a “mysterious past”!? All my old-ball-and-chain did was emerge from his side of the house and ask me what had “happened” in my manuscript that day. He wasn’t commanding me to fill it with happenings!?

Then again, no one declared it my job to clear the dishes at the dinner parties I sometimes haunted back then… Really, Matt should have been clearing, or Darren! Or Buddy! Fucking Buddy hadn’t even helped cook; nonetheless, there I was again, rising from my chair, silently lifting FB’s f-ing plate…

If I knew better, why didn’t I stop? Why did I force my material into an intensifying action plot when I knew I was forcing, faking, flailing, failing, when I felt no fealty to Freytag as a reader or viewer (my fave texts at the time were probably Joy Williams’s weird meander, The Quick and the Dead, and Agnès Varda’s wacky-profound dance-walk, Cléo from 5 to 7)? Why oh why?—when such texts showed me that, however expected or pleasurable the causal event chain might be, said chain is also not necessarily a superb structure for a character acculturated to avoid conflict and even action, to respond (or recede) rather than to cause—a girl, say, or a child, or a girlchild.

Eventually, I realized that this question—if I know better, why don’t I stop!?!?!?—interested me more than what happened, and that I could structure Lonesome Ballroom around it, asking Betty herself to ask it, in scene and via her storytelling, again and again and again!

Mikofsky: There are two senses to the word hysterical. You laced Lonesome Ballroom with black-and-white photographs of women crying, laughing, and maybe both. We have humorists, dramatists, but no hystericists! Not even an OED entry. Are you open to the term? Is yours, as certain PhDers might style it, a “poetics of hysteria”?

Miles, do you know that was I once a lexicographer at the OED? So I can only blame this heinous omission on myself! But I can also affirm that the OED’s project is descriptive—all we have to do to get hystericist in is use it a lot.

Which is to say: hahahahaha-hysteri-yes!!!!?!!!! Let us dismiss hysterical’s dismissive connotations, its implications of disorder or psychogenia (OED 1a!), and focus instead on the fact that humor can tear open a space for tears, admitting the contradictions and complications that social language leaves out! In addition to the visual arc comprised by my lady-laugh-criers, I tried to craft a sonic plot trackable in Lonesome Ballroom’s ha-ha’s, which sometimes get stuck in repeat, then shift as Betty makes minuscule admissions—hee becoming he or her, ha skidding to a stop inside hate. I was worried at first that my ha-ing was too derivative of the amazing pages-long HA! sequence in Lorrie Moore’s great story, “Real Estate.” Then again, we’re hahaing more than ever as life is lived evermore online (one cannot lol alone!), maybe all our fictions should hahahahaha? I was also glad to pay homage to our preeminent hystericist; Moore describes the subject of her early stories as “feminine emergencies” (which brings to mind hysteria’s root, the Greek and Latin words for uterus), and the painful vitality of her prose (“the amazing uterus is responsible for both menstruation and pregnancy” a robo-bro just said when I looked up the organ)—its expansion and involution (also uterine!)—-its rageful play and punny despair (uterine?)—showed me one way of writing about the displeasures of pleasing. (Btw, my own uterus is displeased by our patriarchy’s medical industrial complex and is now thick with scar tissue, hahahahahahahahaha!?!)

In short, if I pretend that it bears little hint of insult, I love this label, am nigh-on hysterically open to this poetics! And were I to shout, “Hystericist!!!” at a writer like Caren Beilin, or the late Fran Ross, or Christine Schutt, or Sabrina Orah Mark, or Deborah Eisenberg, that would just be because shouting “Thank you!!!!!!!!” is a formula in need of refreshing and I’m glad to find funnier ways to be sad together.

The book is structured as a pop ballad: Intro, A, A, B, A. I admire how thoroughgoing that structure is; the bridge really is a turn in the plot, and each verse (all subtitled “How I got here”) repeats an attempt to answer that question.

Betty keeps telling us that the text we’re reading is a song she’s trying to sing. It’s sort of a funny image, the novel longing to be the three-minute-fourteen-second pop track. Other times, Betty’s story seems to wish it were a film of itself. I wonder, as a matter of craft: What ended up happening in Lonesome Ballroom that couldn’t have without the formal constraints you chose?

Generally, the more I understood feminine reactivity + the aforementioned entrapping femme trappings as the book’s subjects, the more I saw how received cultural scripts and shapes (Homeric epic, American songbook standard, movie musical, gallery exhibit, etc., etc.) might inflect Lonesome Ballroom’s style and inform its form. This genre euphoria (!?) allowed me to do something I wasn’t sure would be possible: make a new and, I hope, liberatory, structure for Betty out of old, confining pieces.

Reading the book, I couldn’t help thinking of Kathryn Chetkovich’s 2003 essay, “Envy,” about her relationship with Jonathan Franzen as he became a literary celebrity.Here’s an excerpt:

I see myself as belonging to a generation of women who were raised to believe that we could do and be whatever we wanted — by women who, by and large, had not enjoyed that freedom themselves (and who perhaps envied their daughters for it). I grew up still wanting all the old things — to be pretty, to be good, to be liked — and also wanting not to care about such things.

Somewhere in the middle of Lonesome, Betty, who’s about to have her keys taken away at the bar, draws out a pernicious irony to that same predicament:

It had been argued that ours (like our mothers’ and grandmothers’ before us!) was the first generation of women whose futures were entirely open, whose fates could take any imaginable shape. So why did mine—“How did you get here?” Lizzie repeated—look like this?

Guilt and envy, envy and guilt. (I want what you have, or I have what you want.) There’s a common cultural soil here, complete with tropes like the male auteur: Betty is haunted by one of her own. How do you see Lonesome Ballroom as fitting into or diverging from traditions of writing?

Wow, I hadn’t thought about that Kathryn Chetkovich essay in a long time, though I do remember reading it twenty-two short years ago in my office at the OED, when I should have been scouring the files for hystericist citations! I guess I’d just point out that, in Chetkovich’s case, the auteur-y male author is not a trope, but a living being whose lauding led not just to this embarrassment, but to a response to its response whose lack of rigor still surprises. Sometimes the trope has a torso like a “cello,” and a pool cue that slides “forward and back across [it] like a bow,” as Chetkovich writes, and sometimes that man-childcello is also a writer whose dearest material is well-served by readily available, recognized, and therefore “robust” traditions. Maybe he’s getting paid for it. Maybe your material isn’t, and you’re not.

But hahahahahahahahaha, I don’t hahahahate tradition. Hahahalloween’s cool (sometimes). And my mother is a Medievalist, so I’ve known since I was a child that it’s a tradition, literary and otherwise, to “speke of wo that is in mariage.” I’m sure being aware all my life that fictional tellers can sit in taverns, competing to entertain, was as important as the nights I spent with bloviating bros in bars when it came time to find a frame in which Betty might talk about “traditions of writing.”

I’d love to think that Lonesome Ballroom, a receptive novel about the perils and possibilities of receptivity, might participate in an ongoing receptify-ing of our literature, that it might prove one of many “weird” books that make our broader tradition stranger and therefore stronger, more strapping. Maybe I’d locate it in a sub-tradition of weirdos writing weirdly, and a sub-sub-tradition of weird women writing weirdly about women?—in addition to the heroes I’ve mentioned, I’d love to think LB is conversing with works by Nathalie Léger, Anna Moschovakis, Hilary Plum, Catherine Lacey, Sarah Shun-lien Bynum, Giada Scodellaro, Leni Zumas, Lucy Ives, Christine Smallwood, my beloved Caryl Pagel, so many more!!! This sub-sub-tradition, which often involves remaking familiar story shapes so that they might better contain women’s experiences, has a long and august history (cf. Sleepless Nights or To the Lighthouse or The Golden Notebook), but I felt like it was becoming even more “robust” during the time I was working on Lonesome Ballroom. This is the age of the All Fours group chat, after all (hahahahaha this is also the age of Dobbs)!?

“The puny kapow of the driver’s-side door…”; “The main green gleamed smugly, and I lived in a swirl, no future”; “Yes, I can see it now, that quiet apocalypse of apologies and almost-accusations”… Where do you get your sonic sensibility from?

Well, when I was a kid and my mother needed to work, she’d start reciting Chaucer until I stopped bothering her. Which had me retreating to a basement playroom with iambic pentameter in my ear. There, I’d make up my first stories, which starred, duh/ugh⁴, Barbies, and were scored by a discarded LP of my dad’s that skipped away on his discarded stereo. The fateful sound that accompanied my first story-sounds? Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Songbook, vol. 2., an album I still revere. Repeat listens to its delightful de-lovelies alongside rhymes like Mahatma Gandhi / Napoleon Brandy, all while I structured undoubtedly fucked Barbie-Ken dramas, may have had some effect. I guess I can blame my parents for not keeping me stocked in Montessori blocks and John Cage!?

What are you working on next? And what are you reading right now?

Well, I was stuck so long in this solitary ballroom that I’m kind of terrified to linger anywhere. So I’ve started not one—not two—not three—but four!!!!—different books, thinking that if the suckage and stuckage starts in one doc I can just switch? So far, this mostly means that I never know what I’m supposed to be doing, so I don’t do anything.

I am reading, though… I just finished On the Calculation of Volume I & II by Solvej Balle, whose slow remaking of language via repetition and subtle rearrangement I appreciated. Now I’m onto Bitter Water Opera by Nicolette Polek, who makes elision look easy, wtf!? Also reading a lot of Robyn Schiff because I’m curious about how objects (as opposed to events or characters) might drive a text. Hoping to read Vibrant Matter soon…

Miles Mikofsky is a poet and translator. He’s studied Arabic in Fes, Amman, and at the University of Chicago. He is a recipient of the Lamont Younger Poets Prize (2017).

This post may contain affiliate links.