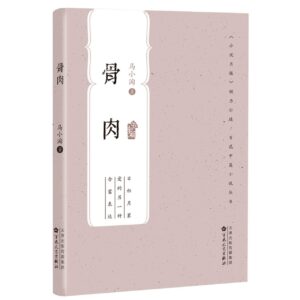

[Baihua Literature and Art Publishing House; 2021]

“The year I turned twelve, my mom eloped with my real dad.”

So begins the novel 《骨肉》 Flesh and Blood. In 1980s China, twelve-year-old Zhang Han quickly learns that the man she’s been calling her father isn’t related to her—her “real” father is the man her mother eloped with. After a terse conversation, Zhang Han and her adoptive father agree to keep their non-biological relationship secret while continuing to live their lives like normal. What does “family” mean, the novel asks, and who gets to belong in one?

The author 马小淘 Ma Xiaotao is part of the post- ‘80s generation of PRC writers, a group including the likes of Han Han, Yan Ge, and Zhang Yueran. Like many of her generation, Ma’s work—from short story and essay collections to novels—grapples with questions about social structures, stereotypes, and human nature through close, incisive writing and detailed characterization. What sets Ma apart is not only her witty, dramatic dialogue, but also the warmth that shines through in her writing: in Flesh and Blood, she upends traditional notions of familial ties and social expectations, replacing them with an earnest examination of how family can extend beyond mere “flesh and blood.”

Told in a refreshingly conversational tone, Flesh and Blood centers Zhang Han’s dynamic with her adoptive father as he continues to raise her in his own gruff way. “You’re just like your mom, wretched through and through!” he yells at her at one point. At another: “I should have realized, you’re nothing but an ungrateful bitch!” When she first gets her period and bleeds onto the couch, he looks at her “a little mockingly, and [says], ‘Don’t you know your own body?’”

More often than not, Zhang Han takes his comments in stride, even biting back at times. With her succinct and quick-witted language, Ma balances two strong-willed characters without letting either dominate. These jousts have no victor: instead, they are part of a display, one that performs underhanded aggression and sharp humor while revealing an underbelly of tenderness. In one exchange, her father, overprotective, attempts to bribe Zhang Han to not join a school trip:

One year, the school organized a visit to an aircraft manufacturer. He didn’t want me to go, because he worried that a two-hour bus ride, roundtrip, wasn’t safe.

“What’s so fun about looking at broken parts of a plane? Can’t you just stay home and watch TV?”

“I thought you didn’t want me to watch TV.”

“I do now.”

“Everyone else is going, so I want to go. I want to join a group activity.”

“I’ll buy you a new outfit if you don’t go. Three hundred yuan minimum.”

Three hundred wasn’t a small sum back then. It was a pretty large bribe for a secondary schooler.

“You know I’m a class prefect, right?”

“Two outfits. Three hundred minimum.”

“Was this how you negotiated with my mom back then?”

“She’s not worth nearly as much.”

Zhang Han and her father also share a fraught and complex relationship with Zhang Han’s mother. The image her father paints of her mother is far from a kind or generous one: “She held all the power in our relationship, she took advantage of my infatuation”, he tells a teenaged Zhang Han. Understandably, it doesn’t take much to sway her against the parental figure who abandons her. We’re told that when her mother elopes, she leaves behind a note misspelling Zhang Han’s name. It’s unsurprising, then, that Zhang Han holds tightly onto her resentment, meeting her mother’s delicate efforts to reach out with icy words. Even as her father’s attitude towards her mother softens, Zhang Han remains resolute in her rage, and it’s not until her mother’s passing that she’s able to reckon with her feelings of resentment, guilt, and loss.

Ma’s depiction of the complex bond Zhang Han shares with her parents—her biological mother and adoptive father—sheds light on her definition of family: one that is not limited to rénlún, the concept of “moral principles” that forms the basis for human relationships in neo-Confucian thought and social order. Ma writes in an afterword:

What we call flesh-and-blood kinship is not limited to biological relation. […] I’ve always felt that bonds between people are defined not by biological relation or rénlún, but by the relationships that form when people spend time together, day in and day out—real relationships that often contain random and mysterious flickers of like and dislike.

The figurative “flesh and blood” shared between family is not biology, Ma argues, but the emotions and relationships, almost tangible, that are formed over time. Throughout the novel, Ma makes the case that rénlún is insufficient for determining real, lived human relationships. Zhang Han’s relationship with her biological mother, in the system of rénlún, is recognized and given weight—but that doesn’t reflect their reality. On the other hand, in this system, her relationship with her adoptive father is nothing more than that of two complete strangers.

In the interest of avoiding shame and questioning, Zhang Han and her father keep their non-biological relationship a secret throughout the novel. They perform a father-daughter relationship for neighbors and extended family, becoming father and daughter not only in their authentic emotional bond, but also within the social fiction of rénlún that they perform. In this sense, rénlún becomes nothing more than a performance.

Through its critique of rénlún, Flesh and Blood engages in a rich variety of performance imagery: from a reference to èrrénzhuǎn shows in the opening chapter to allusions to the 1983 film Papa, Can You Hear Me Sing (Dā cuò chē) and the 1999 play Rhinoceros in Love (Liànài de xīniú), the novel teems with performed culture—as though Zhang Han herself is aware of the performativity of the relationships in her life. When she meets her biological father, she critiques him for his performed politeness (“Shaking my hand, as though there are reporters present! It’s not like we’re on the news”). Shortly after, she writes, “Not even a novelist could have come up with this scene.” This slightly jarring moment reminds us we are in fact reading a scene that a novelist did come up with—it also reminds us of Ma’s brilliance in crafting her characters’ shifting exteriorities and inner lives.

Anchoring the novel’s snappy wit and cleverly self-referential humor are some real, heartfelt emotional moments that feel authentic and earned. A college-aged Zhang Han and her father talk idly as they watch the sun rise over a beach, and he reminds her to keep her mind open, to work hard but not to neglect rest, and not to live too frugally. A magpie, a symbol of joy and good fortune, lands hear them, chittering away. She imagines that it’s repeating her father’s well-intentioned nagging. Her father suddenly says to her, “I’m craving salted duck eggs.” She replies, “I bet it was the sunrise that made you think of salted duck eggs. I also thought of them.” There’s an unspoken understanding between them, gently respectful while also easy and carefree. And there are moments of anger and frustration, too, but they’re mediated by a deep fondness. As Zhang Han says earlier in the novel, “True kinship always leaves space for pestering or hurting each other, because blood keeps you intertwined. Because that bond is forever, you don’t have to tend to it as much.”

Flesh and Blood feels fluid and unburdened by the emotional weight it carries—but this tiny novel packs a punch. Ma paints a tender portrait of found family: one that is determined not by rénlún or biological “flesh and blood”, but by how people choose, again and again, to be each other’s family.

Fion Tse (she/they) is a translator working between English and Chinese (Cantonese and Mandarin). She is currently pursuing an MFA in Literary Translation at the University of Iowa, and her work has been published in Asymptote, World Literature Today, and The Shanghai Literary Review, among others.

This post may contain affiliate links.