This essay was first published last month in our subscriber-only newsletter. To receive the monthly newsletter and to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider joining us on Patreon.

Pop culture is awash in repetitive redos and warmed-over tropes. But even by those standards, slashers stalk relentlessly from iteration to reiteration. To watch a slasher is to watch the sliced up remnants of other slashers, reanimated and sent out to perform the same deadly rituals once more.

The famous shower scene in Psycho (1960) is chopped up and the bits reassembled as the bathtub scene in Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), and/or as the outhouse scene in Friday the 13th: A New Beginning (1985). The grotesque hillbilly antagonists in Deliverance (1972) crawl out of the backwoods to menace the (not-so) innocent city folk in The Hills Have Eyes (1977) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974). The killer is mistaken for a masked boyfriend horsing around in Halloween (1978) and again in Scream 2 (1997). Final Girls—the iconic protagonists who survive and/or kill the slasher—keep rising from apparent death. And of course, there are infinite sequels and remakes and remakes of sequels and sequels of remakes to just about every film mentioned in this paragraph and really to any slasher at all.

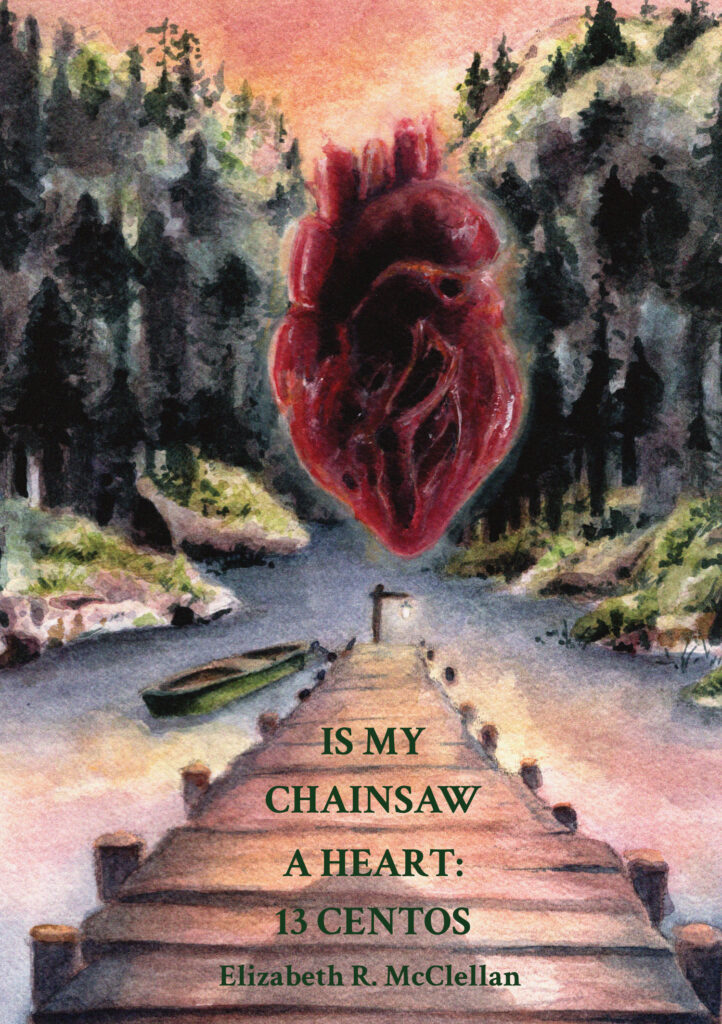

If the truest slasher is the most cobbled together and derivative slasher, then the truest slasher film may be a novel: Stephen Graham Jones’ relentlessly referential volume My Heart Is a Chainsaw (2021) which explicitly references and analyzes and recapitulates just about every movie in the genre. And the truer than truest slasher may be Elizabeth R. McClellan’s newly published poetry collection Is My Chainsaw a Heart: 13 centos composed of quotations and vivisected bits of Jones’ book, each section titled with the names of iconic Final Girls: Laurie from the Halloween franchise; Clarice from Silence of the Lambs, Alice from Friday the 13th, Sidney from Scream.

Slashers are always exercises in recognition, but by the time McClellan has chopped away the features of plot and character and narrative, all that’s left are those quivering scars of familiarity, slasher scenes diced and rearranged into a comforting, disturbing montage of connected disconnection.

One last scare

Because she fucking knows this genre

His blood—his life—slips out for real this time

I trusted you, Dad.

She’s still recording all this on her phone.

So it begins

This is her last time to run away

all the stories of this night

are going to coalesce around

her calculated revenge against the town

But she had a moment, didn’t she?

Jones’ collage of slasher hallmarks and tropes is resegmented and recollaged, turned into a scare, a genre, blood, a betrayer dad, a recording, a story, a night, a revenge, a moment. It’s a ritual gestured to rather than enacted, which makes the ritual seem even more inevitable. And it’s a trauma cut off from specificity, from memory, and from history—which makes the trauma more unassimilable, and therefore more inescapably its own bloody psychic weight.

“a dark heart in her hands”

Any slasher fan, and even most slasher tourists, are aware that the genre is about trauma. In the first place, the plots usually hinge on an incident of horrific violence: a Black boy mutilated and tortured to death for his relationship with a white girl in Candyman (1992); a child murderer incinerated by an angry mob in Nightmare on Elm Street (1984); a girl killed in a car accident in I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997). The initial scene of violence leads to revenge (natural or supernatural), and the revenge functions as a recapitulation of the initial scene of violence. The compulsive genre borrowing and reworking is not (just) the crass logic of the market; it’s a representation of the compulsive return of trauma, in which the same primal scene is staged and restaged, like a bloody knife rising and falling forever.

In Jones’ My Heart Is A Chainsaw, the initial violence is multiple and proliferating; the book has at least two slashers wandering through it, maybe three, conceivably more. There’s one main character though: Jade, a high-school senior in Proofrock, Idaho who’s obsessed with slashers.

Part of that obsession, we learn, is perhaps due to her own history. Her father, with whom she lives, is emotionally abusive and, on at least one occasion in her childhood, sexually abusive as well.

Jade is deeply invested in the idea of the slasher Final Girl who survives and turns the tables on the slasher. In part, that’s because she herself wants revenge—on her father, on the school and the sheriff and the town that didn’t protect her. But it’s also because she wants to believe that some strong, fearless girl (like her new friend Letha Mondragon) will rise up to protect her, as her estranged mother did not.

Jade’s mother is white; her father is Native American, specifically Blackfeet (as is Jones himself). Jade’s abuse is doubled by, or parallels, the historical trauma of settler colonial violence. Proofrock, located on Indian Lake, is supposedly haunted by the spirit of Stacey Graves, a Native girl accused of witchcraft and killed by whites at some indeterminate time in the town’s distant past. The history of invasion and conquest is reiterated by the development of the new wealthy community Terra Nova across the lake. Stacey Graves’ ghost is disturbed by the settlement so she starts killing, slowed only by her unhinged jaw, broken during her torture, which she has to periodically adjust before she continues her rampage.

The first victim in the novel, a Dutch boy on vacation in Idaho, shouts when he sees Stacey (offscreen), “Wat is er mis met haar mond?” That means, roughly, “What is wrong with her mouth?” It’s a statement that is going to be meaningless, or uninterpretable, for most English speakers, even as it calls attention to Stacey’s broken jaw. That jaw prevents her from speaking, just as Jade has been silent about her rape for most of her life. Violence overwrites communication; trauma cannot be voiced, or can only be voiced in a language that can’t be assimilated. “Does she even understand words anymore,” Jade wonders about Stacey, and implicitly about herself, “or does she only understand death?”

In McClellan’s reworking of that passage, the first half of the sentence is excised—along with narrative and character. What’s left are evocative, painful snippets of language, which—like the Dutch victim, like Stacey, like Jade—can speak only obliquely, and only of trauma.

squirming deeper into the decay

the party on the water

invading her lake

does she only understand death?

the red surface of these waters

the night splitting in two

Similarly, the Dutch boy’s scream is in McClellan’s poem is no longer attached to the Dutch boy; his actual dismemberment in the novel becomes a ghostly, metaphorical dismemberment, in which his death and trauma erase his self and existence from narrative and memory.

I’m cold and scared

some disturbance on the surface of the water

never should have come

a profanely intimate sound squelches

in human, except more primal

only scream once

“Wat is er mis met haar mond?”

sorry to America too

a dead horse floating underwater streaked red

In the novel, the “I” who is cold and scared is the Dutch boy’s girlfriend, waiting for him in a boat. But there is no clear “I” in the poem. It’s a disembodied expression of vulnerability and fear, which is more intense because it is disembodied. There is no self there except for the slasher trope of incoming retribution, without tongue or jaws, without comprehensible elucidation. Words for McClellan are a chainsaw, carving up red streaks of meaning, until all that is left is a primal squelch.

“I just want you to-to be safe”

There is another possible referent for the “I” in McClellan’s “I’m cold and scared,” which is McClellan themselves. In the absence of clear characters or plot, the (very) occasional “I” in the poem becomes, at least potentially, lyrical and confessional. When McClellan says, “I just want you to-to be safe,” they are (maybe) expressing their personal desire to help and protect Jade, and all the Final Girl victims, and maybe Stephen Graham Jones, and maybe you, the reader.

Expressions of care may seem out of place in a brutal genre like the slasher. And yet, according to critic Carol Clover (who Jones quotes in his epigraph), identification and a kind of empathy are central to the genre.

In her classic 1992 study Men, Women and Chainsaws, Clover argued that slashers were not primarily sadistic but were instead masochistic. Imagined (though not always actually) male viewers are encouraged in slashers to project themselves into the body, the perspective, the position of typically female victims. Men watching slashers feel women’s vulnerability and terror—that is, until the last scenes, where the Final Girl seizes that phallic chainsaw and turns it on her aggressor, flipping the positions of victim/victimizer, and of male/female.

The slasher, then, in Clover’s view is a kind of gymnastics of identification, in which viewers (ultimately of either gender) identify with women and men alternately in a flickering sequence of empowerment, disempowerment, masochistic fear and sadistic righteous revenge. The slasher not only slices up other slashers; it also hacks apart viewers, who are severed from their identities in order to become enmeshed in the mechanisms of narrative and trauma.

Jones and McClellan reenact these severings with a few additional twists of the knife. Jones is, again, Blackfeet, and the novel is (like many of his novels) about indigenous community and a history of indigenous genocide. His book is a chainsaw because he’s cheerfully imagining revenge on those who murdered his ancestors.

As per slasher default, though, Jones’ novel is not just about him, but about who he is not. Jade is a girl, not a boy, and her trauma is specifically at the hands of her abusive father (who may have been abused himself). In his lengthy acknowledgements/ afterward, Jones talks about discovering the high rates of abuse in Indian communities. “I stumbled onto a read about a young Native girl in Arizona who killed herself after being molested by her (Native) father,” he writes. And concludes, “I did now have someone to write against: that father who was never a dad.”

Writing against here means, in part for Jones, writing against himself—at least to the extent that he is taking the part of daughters against fathers. He isn’t that father, obviously, but he nonetheless shares with that father a position and gender, just as the non-Native inhabitants of Proofrock share with their ancestors the position of colonizer. Part of the power of the slasher, and part of its pain, is that it demands you recognize yourself in both abused and abuser, that you see the potential in yourself to be harmed and to harm.

Because of his background, his gender, and because of the slasher dynamic of cross-identification, Jones both is and isn’t Jade. Similarly McClellan—who is white, nonbinary, and has worked in domestic violence law—both is and isn’t Jones. McClellan uses Jones’ words, but in repeating those words in their own voice and in a new context, reference and identity shift.

Crone Mother?

horror girl

paddling away from something

scream splits the night cuts off just as fast

that same language

In the novel, Jade is watching the deaths of the Danish students on video. “Crone Mother” is her garbled effort to interpret unfamiliar Danish words. “Horror girl” is Jade ironically referring to herself.

But in McClellan’s pared down reworking, “Crone Mother?” becomes a question to which “horror girl” is the answer—a question and answer in which witch and victim, mother and daughter, blur and run and scream in the night together in the same language. Comfort and solidarity means sitting together in violence—perhaps as the one to whom violence is done, perhaps as perpetrator, maybe as both.

One of the poem’s loveliest juxtapositions is at its conclusion. McClellan did not stop with their reinterpretation at the end of the novel, but instead went on to quote and rework Jones’ afterward. That means that the poem ends by respeaking not Jones speaking as storyteller, but Jones speaking as himself. The last lines of the poem are:

No dad’s ever been so lucky as I have

sleeping on the old couch in the glow of that television

Thank you, Nancy, for keeping me safe all those nights

My heart is a chainsaw, yes, but you’re the one who starts it.

“Nancy” here is, in context, Jones’ wife. But stripped of its immediate referent, and with the glow of the television there (not to mention the nod to sacking out on the couch), it’s impossible not to think of Nancy, the Final Girl from Nightmare on Elm Street, who is attacked by the supernatural slasher while she sleeps. A personal relationship opens up into a relationship with dreams, and in that dream McClellan becomes simultaneously the lucky dad, the wife, and that Final Girl daughter. Who keeps us safe all those nights? We do, by the stories we tell and the stories we cut apart, with chainsaws and with hearts.

Noah Berlatsky (he/him) is a freelance writer in Chicago. His full-length collections are Not Akhamtova (Ben Yehuda Press, 2024), Gnarly Thumbs (Anxiety Press, 2025), Meaning Is Embarrassing (Ranger, 2025) and Brevity (Nun Prophet, 2025).

This post may contain affiliate links.