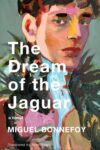

[World Poetry Books; 2025]

Tr. from the German by Ann Cotten and Anna-Isabela Dinwoodie

On the nine-hour train ride back to Berlin from Vienna, a young man takes the seat next to me. He asks whether I think it’s safe to leave a suitcase back by the train’s entrance, out of sight from our seats. “It’s a good question,” I say. “Is it heavy?” Yes, very heavy. “So you’d really have to go for it if you wanted to steal it. You’d really have to want it.” He nods, not exactly reassured, but stays seated.

I pull up my review copy PDF of Liesl Ujvary’s Good & Safe, translated from German by Ann Cotten and Anna-Isabella Dinwoodie. Ujvary was born in 1939 in Bratislava and relocated to Austria at the end of WW2. Through slavic languages, smuggled soviet texts, and experiments in sound, Ujvary arrived at poetry. In 1977 her debut Sicher & Gut appeared with Rhombus Verlag, a collection of incantatory list- and block-poems that went largely unnoticed. Hardly surprising—its kind of wisdom rarely survives the gallows.

The book opens with a section called What Holds the World Together. Personally, I’m desperate to find out what IS holding the world together (is it poems?), but the reader who has a similar desire will be disappointed. What follows are a set of laconically arranged objects:

Tough times — weak knees

Full breasts — empty pockets

Hot nights — cold coffee

Sour grapes — sweet life

[…]

I imagine each of these pairings as the x and y along which life is measured, a pretty convincing metric of what it is to be alive. But soon the real experiment begins: on the next page, Ujvary’s poems unbuild the very conditions that language pretends to stabilize:

this is better

democracy is better than dictatorship

butter is better than margarine

schools are better than military training camps

sex is better than booze

humans are better than computers […]this is the same

democracy is like dictatorship

butter is like margarine

schools are like military training camps

sex is like booze

humans are like computers […]

How cozy it seemed in that first list. How reassuring to be told we are on the right side of history. Butter is definitely better than margarine! This is GOOD! This is SAFE! But alas. The things in Ujvary’s lists do not merely rub against each other; they contradict, complement, and depend upon one another. Each term articulates the other’s position, revealing their uncomfortable unstable entanglements. Suddenly, opposites are not opposites at all but interdependent coordinates within the same ideological grid, school, military, democracy, dictatorship. They play out scenarios together: humans are like computers / humans are better than computers — which one is it? The sequence continues:

this is better

poems are better than advertisements

students are better than cops

truth is better than liesthis is the same

poems are like advertisements

students are like cops

truth is like lies

With the smallest shift the entire semantic field tilts and Ujvary unsettles the soothing properties of language. A single syllable is enough for language to betray its own scaffolding, leaving words bare as generators of ideology, waiting for someone—anyone—to assign them direction. These poems pour liquid bias and powdered syntax into the container of the page so that language begins to sprawl like a science fair volcano.

Every once in a while the man next to me turns around to look at his suitcase. “Would you like to swap seats?” I offer, “to keep an eye on the suitcase?” “No, no.” I am looking at his computer. He is taking an online course on AI. I wonder if he’s a coder. Then again, the course looks very fun, very friendly. Maybe he is just a person alive wondering what the hell is up. I glance at the URL. I close my PDF, and sign up for the free course on my laptop. For the next fifteen minutes I learn that there is no such thing as “an AI” — no singular entity. It is more a method, a strategy, an approach to language “learning,” and, as such, is entirely vacuous.

In 1977, Vienna had been busy reinventing itself: the underground train was about to open, and the city carried the scent of a new conservatism—one that sought to redefine “Austrian” identity with a nicely polished veneer of innocence set against the backdrop of a guilty “post-nazi” Germany. Butter is definitely better than Margarine! Our country is definitely better than their country!

That year Apple also released its Apple II, the first successful personal computer. Fritz Wotruba’s brutalist church, made entirely of concrete, was revealed in Vienna’s Liesing District, and dissolved the trinity into abstraction. A huge earthquake in Romania left only concrete buildings intact. While concrete poetry had its heyday in the sixties, people behind the Iron Curtain initiated so-called mail art networks. Artists from East Berlin took to sending out pieces of language containing opaque visual poems in an attempt to slip them past the STASI.

It can’t be said for certain what influenced the poems in Good & Safe, but it seems safe and good to assume a kind of osmosis at work. Read against the Cold War communication economy of mail art, and its letters, lists, instructions, all passing through systems of surveillance and comprehension, the title Good & Safe becomes morosely hilarious. The poems already anticipate a world where every sentence must pass inspection. A later section of the book, Autobiography with Instructions, continues this logic, built of text blocks and questions pertaining to the text.

Please answer the following questions:

1. Do you enjoy grocery shopping?

2. Is there a supermarket in your neighborhood?

3. What are the advantages of self-service?

4. How much does a kilo of sugar cost?

This “quiz” is reminiscent of ubiquitous questionnaires, like a government census-type survey, or a market assessment survey by some grocery store conglomerate who wants to expand into new neighborhoods, or endless tirades of English™ language comprehension tests any non-native English speaker has to undergo if they want to qualify for speech inside of institutions. In echoing the test form, Autobiography with Instructions plays with the “neutral” voice of rational authority. But from behind that surface tilts a subject in slippage, emerging. Something flickers in revelation: “What is your brother’s (your sister’s) job? What is the atmosphere like in your family? Do you keep in touch with your family members?” Ann Cotten notes that Ujvary was supposedly courted by the KGB but refused cooperation. The repercussions of such refusal are unclear, but Good & Safe contains texts, letters that communicate something deliberately obscured, a bag heavy in the back of the train “What do you talk about? Do you like to talk about your health? Do you talk about mutual acquaintances? Is your friend interested in the arts?”

Or, consider these switchbacks: “I have a homeland no I don’t / I have a car no I don’t / I have two hands no I don’t / I have good luck no I don’t.” Sentences and their implicit loyalty to identities are swiftly installed and swiftly taken back down again “as if the author were an illegal street vendor.” The negations in these lines expose nation, body, fortune, and ultimately the act of speech itself as a highly volatile currency. I have a language, no I don’t.

In the afterword, Cotten recalls that some of the best writerly advice they ever received from Ujvary was to “always write to sound like a translation.” This is delicious homework for a translator—someone so often asked to disappear inside their work. Translators Anna-Isabella Dinwoodie and Ann Cotten don’t exactly appear in the translation, but I imagine them smiling as they pass through the Südbahnhof and the German sausage-names that double as place names in these poems. Cotten, who has previously translated Rosmarie Waldrop, is herself an acclaimed experimental poet wreaking havoc on the German language—popularizing, for example, gender-expansive grammatical structures. Taking on the anarchic body of Ujvary’s work, then, makes perfect sense: here, the translator is granted permission to be faithless—though perhaps they always were. Translation is typically judged by its “fidelity” to the source text, yet what does fidelity mean when the “original” resists singular belonging? Can one be faithful to a lover who is already a promiscuous cheat? Ethical non-monolingualism, anyone? But I digress.

To write as if it were a translation mobilizes a distance; it’s including no return address; it is a kind of withholding inside of endless proliferation (i’m good / i’m really good / i’m just fine / i’m doing great / i’m not doing so well / i’ve actually never been better). “Where are you from?” the man next to me suddenly asks, and I quickly swipe my screen back to Good & Safe before he notices that we are doing the same activity on our computers. How cozy—and how dangerous—it is to ask a question (“What holds the world together?”) and expect an easy answer in English™.

Good & Safe is an anti-manual of how language is used, cataloging the possibility and danger therein. Ujvary shows us that language is not going to be loyal but neither are we. In Prague, the man leaves the train with his suitcase, but later I notice that he forgot his jacket in the overhead compartment. “Good” and “safe” all depend on who it is that you are talking to. A church is revealed, a tremor, your suitcase is safe, the train stops. Anything can be said. Our safety and our demise lie in this.

a.Monti is a cross-disciplinary poet, educator and translator. They are based between Berlin and New York City but were born in an elevator in Rome going up to the third floor. amonti.net

This post may contain affiliate links.