The introduction of Arcicologies features several unlikely moments. The author makes a case, picked up and just as immediately put down, that the geographic North is exoticized and other-ed in the same way as the East in Edward Said’s Orientalism. He mixes metaphors in sentences that serpentine just slightly out of his grasp—in describing another academic’s statement about multiple Norths, he comments “To follow his logic is to “kee(p) the twilight” that hovers between specificity and unrecognizability, be it the topography or the nature of knowing altogether.” Duckert claims that “hypermasculinity is synonymous with the cold,” that “The artistic disorientation of “Norths” act centripetally and fugally…”, that “Winter is coming both at and for you.” Apropos of nothing, he quotes another academic to state “almost everything that consoles…is false.” This is all within the first four pages.

I don’t quote and paraphrase to invalidate the contents of the book, but to affirm that, like Ernest Shackleton realized at the beginning of his stay on Elephant Island, readers of Arcticologies look forward to a harsh passage through unforgiving terrain. This academic book operates in a realm of non-linearity and abstraction so distended that it is difficult to hop safely from one careening paragraph to another without falling into the icy waters of incomprehension.

My encounter with Arcticologies was heavily contingent on my own status as a non-academic reader. It is admittedly hard to appreciate this style without participating in the epistemological and class sphere in which the author of Arcticologies and other similar books exists. This makes my engagement with the text somewhat strange, or, as Duckert repeatedly, incantatorily, states, “promiscuous.”

It is not a novel insight that academic writing is dense. And Arcticologies does not hide its academic-ness—it is published by the University of Minnesota Press, blurbed by other academics, and written, of course, by a professor of English. And yet, there are mysteries around this type of academic writing, a specific and separate genre from run-of-the-mill linguistic opacity. For instance, none or few of the foundational studies cited in the introduction use this particular literary register. I wondered, as I picked my way through the text, why there are passages like “The snowflake stymies the processes of inductive and deductive reasoning by which humans burrow into the heart of hexagonal matter in order to sleuth out its unerring principle” (noting that no two snowflakes are alike).

I both am and am not the intended audience for this work, and for this genre writ large. Arcticologies contains several exhortations towards catholicity in its readership, stating that it “hopes to enlist additional voices” in the conversation on cold, and that it extends “an inclusive membership…to those excluded too often and for too long.” Regardless of the sincerity behind these invitations, I took them as a pass to engage with the work as a welcomed guest, and not as a trespasser.

Holding up Arcticologies as an exemplar of an entire, easily parodied genre is not fair, nor is it my intention. I hope instead to formulate a theory of why this language and style might be employed, and to evaluate Arcticologies on its own terms. Any analysis of Arcticologies has to begin with an examination of the style. It is the single most distinctive feature of the text, and presented a formidable barrier to my understanding. The author, Lowell Duckert, is a professor of English at the University of Delaware. His previous published works include theoretical forays into eco-criticism and a book (oddly parallel to Arcticologies) about the essence of wetness, For All Waters.

The style of Arcticologies can be notated in several more obvious features that jump out in an early reading:

- A gesture towards future action, contents unspecified.

- bi/furcation with forward slash marks, notating the dual and opposite meanings of a word and its affix.

- Paren(theses), interior or exterior, intended to complicate a clause.

- Quotation marks around a single word, without explanation

- Puns.

- Offhand citation without preamble or introduction.

- An outsized authorial presence, manifested in intermittent personal asides (a narrative of the Dr. Duckert’s participation in a charity cold plunge opens the book) and frequent analytical excurses into the author’s idiosyncratic interests.

- An ever-present and somewhat ghostly horniness, descriptions of “promiscuity” and “intimacy” between concepts, people, places, and elements.

Here is an exemplar paragraph, fittingly describing the disorientation of directional North:

North is (a) disorientation. Most of my texts are north-looking by virtue of their setting: North America, Northern Europe, and those various islands and waters fringing the Arctic Circle that connect the two continents. Metropolitan life is one stop on my longer horizontal scan of the northern hemisphere. But there are many definitions of “north”: geodetic/geographical (“true”), magnetic, grid, and astronomical. To “go north” is slang for being “on the up”. When something “heads south,” it goes awry. But its various meanings do not recalibrate headings as much as cause to the idea of “north” itself to contort. Peter Davidson remarks that “north” is a “shifting idea” because it always recedes from our attempts at encapsulation.

I will confess that I had a sudden and visceral reaction to this style. The text does not, to put it lightly, flow. Reading it feels like scooping wet snow with a large shovel on an unseasonably warm winter morning—it is dense, close-packed, formed into long and undifferentiated paragraphs. The puns and internal jokes that stud each sentence make it hard to understand any given paragraph. More often than not, any particular thought is not connected to any succeeding paragraph. As I made my wet, weary journey through the book, the puns began quite quickly to wear as heavily as a soaked parka.

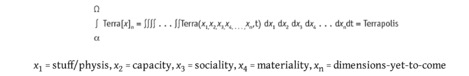

I have come to believe, however, that this style has a readerly purpose, or at least an effect. The otherworldliness of the text invites engagement on a more-than-superficial level. Donna Haraway, the theoretician of the “Cthulucene,” is a prominent influence within this high academic genre and has deployed the style successfully. For example, in one chapter of Staying with The Trouble, Haraway presents a “fabulated multiple integral equation”:

There are better ways to express ideas, certainly, if clarity is the goal. But Haraway’s writing does not guide the reader along a well-tended path towards understanding. Instead, it provokes linked insights that are caused, but not necessarily substantively linked, to the text.

This style and genre have a generative power. The equation above, for instance, does not elucidate any precise point about interspecies collaboration, but does offer an oblique way of thinking about the world. What other insights can we unearth by thinking of unknown facets of the ecology as linked indeterminate variables, whose values go up or down in relation to each other? What does it mean to express something mathematically rather than verbally, and is that precision, as in this half-joking equation, illusory?

Generativity is a large focus of Arcticologies, and of eco-criticism as an area of study. Reading Haraway, it is difficult not to feel, in some way, thrilled. Staying with the Trouble gestures towards impossible, or at least improbable, connections, rare moments of potential in a prevailing political atmosphere of despair. And indeed, this is how “lay” groups have engaged with Haraway, appropriating the general gist and feel of her work in order to buttress a range of artistic and political projects, from science fiction writing that questions where humanity ends and nature begins, along with the horror one might feel at approaching that boundary (Jeff VanderMeer, Margaret Atwood) to installation art embodying the scent and physical presence of ideology (Anicka Yi). The provocations in Staying with the Trouble make us question boundaries, our perspective on ourselves and each other.

Arcticologies is not successful as an example of this literary/academic hybrid writing. Firstly, the structure and style of the book limit creative engagement. Duckert introduces the concept/genre of arcticologies to open the book:

This book is a compilation of “Arcticologies,” my loose term for sixteenth- and seventeenth-century stories that have an invigorating role left to play in the retelling of climate history and our fraught futures with cold.

There are several problems with this pursuit. First of all, the perils of the high academic style intrude, even to this statement of method. What does “invigorating” role mean, other than offering the opening for a pun? Can these fragments impart energy or motive force to an ongoing (largely political or at least politicized) re-evaluation of the earth’s climatic history?

The answer is no. They are neither explained nor historically situated. Not one of the “arcticologies” contains so much as a skeletal preamble placing it in history, or even a timeline. Most do not note the date of publication. The text presents only analysis, which is to say it presents puns and further references to academic literature. Furthermore, the choice of sources reifies the current narrative rather than altering it. The narratives Duckert chooses to analyze are almost uniformly European, male, and elite.

The really troubling aspect of the book is political. The introduction promises both to look at a retelling of climate history and of a fraught future, as well as the above promise to “invigorate” debate. What does “fraught” mean, here, particularly with reference to a shared future (“our”)? Is it a reference to the political context of any climate discussion? Or a decolonial project, referenced semi-randomly throughout the texts? None of these questions are ever answered, or even seriously treated. The book really does not interest itself in politics, nor in history. It is interested in itself, in its own use of punning language, orthogonal connections, provocations. It does not engage with the questions that ostensibly animate it, but instead gently floats away, unconcerned with its own legibility. It inhabits an ouroboros—its project is interesting and timely due to its political relevance, but it chooses to instead pursue questions that are neither imaginative nor important enough to keep a reader’s attention. Can there be sexual intimacy between man and ice? What would it mean to wish for accidents, rather than against them? Can one listen to an ice cube?

Then again, there is a class and epistemic community in which none of these weaknesses need to be barriers, in which a text like this provides a perfectly serviceable line in a list of “publications.” I give Professor Duckert the great credit that Arcitologies is, to my reading, not that. It pushes too far into the abstract and plays too much with language to simply check a box in an academic CV. This does not mean that the book successfully bridges the gap between expertises, or makes its subject matter self-evidently important, for which I felt a certain disappointment unrelated to the text itself. I would love to engage in the discussions that Duckert gestures towards! I would love to really know how early modern people thought about snow! More in sorrow than in anger, and per the book’s own punning syntax, Arcticologies left me cold.

Eamonn Gallagher is a writer and researcher living in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with his wife, son, and cat.

This post may contain affiliate links.