The following is a conversation between Isabella DeSendi (Someone Else’s Hunger) and Adedayo Agarau (The Years of Blood), each celebrating their recently published collections of poetry. Their conversation traces the resonances between the dismembered boy found near Liberty Stadium and the violence done to the body through sexual abuse and physical violence, among other griefs (and blessings!). They consider prayer, faith, and ritual– whether it is a call to prayer from a masjid’s minaret, or a santera learning to pray again, learning the way of their body in the world. Between “boys who never joke with food” and “mofongo, mythos, music, mules—like us, the beasts of burden,” the barrier of distance is confronted through the intersection of culture, language, and trauma. Their conversation aims to ruminate on the ways poetry can offer and sometimes even lead us to salvation, excavation, and healing.

Adedayo Agarau: Both collections navigate the inheritance of memory, whether bequeathed or forcefully given, they dwell in haunted rooms—bodies marked by silence, the rituals that fail or save us, and the tangled thresholds of memory, violence, and survival. How do you think memory operates in poetry? And what are your views on survival today?

Isabella DeSendi: I have a terrible memory, and so poems are what I turn to when I need to discover or re-discover something that has been forgotten or repressed or remains buried in me still. Memory is a powerful tool, but it’s susceptible to the same flaws of language in that it is designed and maintained by humans who are inevitably fraught and flawed. When I write, I’m less interested in capturing the full totality of a memory, of a moment, so much as I am curious about peeling back its layers and looking at its truth. In a poem, everything exists that needs to exist. I am at no risk of forgetting something once it’s written because the watermark of that moment exists on the page forever. The act of surviving is slipperier than this. Once, I believed that writing through trauma would clear it, as if I could empty all my dark parts into a big body of water where they would liquify and dissipate, dissolve themselves away. Surviving is a continuous act, a constant reclaiming and reminding and yearning toward freedom– that is one thing writing this book has taught me. It permits me to have good days and bad days, and it is the persistent act of working through it daily that inspires me to keep going.

I agree with you, Bella. Surviving is a continuous act—and writing, whether poetry or otherwise, is in some way a ritual, a forsaking of the body, a tendering of the self at the altar of what it’s been through. Sometimes I wonder why we’re writers, why we do this to ourselves—nail our bodies on the cross and walk through shame over the thorny fences of memory. If you bled in a past life, writing means you are documenting this bleeding by walking over the thorns, carrying your own cross through the forest, heaving, sighing, tired. But I am the only one, right now, writing about the kidnapping in Nigeria as if it’s not a national tragedy—that is to mean that the writer has to save their country, the writer has to be the conscience of their people, the writer has to write. Something has been broken since I was born. I guess the writer’s urge to return to the page to document—to eulogize, or to write a dirge—refuses to let the dust settle. The Years of Blood will not fix anything or even bring Damola back to life, but I believe the collection has now become part of our national consciousness. By refusing the kind of violence silence does to us as both the singular body and as a country or a collective, through the collection, The Years of Blood, we have an archive to refer to when we think of the forced disappearance happening in Nigeria and how a young boy from Ogunleye street, grown now, is walking himself and everyone else who reads the collection, through the profound silence of our country at one of, and still, its darkest times.

I love thinking of the work as an archive for a national consciousness, a collective wound. In The Years of Blood, you write, “It could be me whose blood is crying… It could be my ghost finding the touch of its mother in a house where the doors are shutting against the portals of grief.” There are also numerous mentions of violence committed against your family members, and the boys and girls in your community. Does it ever feel daunting writing about the pain of your loved ones? How do you approach writing about catastrophe and violence when the subjects are people you know and love?

There is something temporal about loving that puts us in front of a gun. It is as if we are constantly attempting, by writing toward, or away from such events, to rewrite the event, hoping it had had a different outcome. There is an acute awareness of the responsibility of witness here. This awareness is also evident in your poem, “Portrait of My Mother as Tiger,” in the way you write “tienes hambre” as both a question and a wound. One night in Iowa, I couldn’t sleep because I was heavy with the guilt of writing, or perhaps what they refer to as survivor’s guilt, so I took a long walk from 7th Street, Coralville, to Iowa City. It had just snowed, and it was -12 degrees. I remember thinking my body might freeze into the exact shape of my guilt—bent forward, arms wrapped around myself.

I kept thinking about the mother of one of the boys, how she searched the streets calling his name. She would wake up in the morning and ring bells like an evangelist laying curses on people who took her child, her only child. Similarly, my aunt whose son, Damola, was kidnapped and erased from public record, almost went mad. While I try as much as possible to stay closest to the most intimate memory, I feared I couldn’t even bear seeing all the details in a book. When the woman found her son in the large canal at the other end of the street, I recall seeing an ease written on her face. Perhaps that is what I am writing toward, that ease. That which even poetry may not be able to collocate entirely.

Isabella, I’m curious about something in your work—in “I Dream of Havana,” you write about wanting to “tell the women in your dreams I’ve had enough. I’m coming with you,” and then there’s that moment where you say “No, Father, I forgive you.” There’s this sense of inherited witness, of carrying stories that happened before you were born, in a country you’ve never seen. When you write about your people’s hunger in Cuba, about your abuela slashing the rooster’s throat, how do you navigate the responsibility of carrying someone else’s trauma? What does it mean to be a witness to a wound that isn’t technically yours, but lives in your body anyway?

What I originally saw as a responsibility, a burden to bear, slowly became the light that carried me through the dark hallways of the traumas these poems attempt to reckon with. When I tried to write about my pain, my trauma, solely, it’s like you say– the weight of it was nearly too much. But when I consider myself a voice in the repertoire of a collective wound, I feel less alone in the carrying. Writing through the stories of my abuela and my mom and the women and immigrants who came before me wasn’t a duty, it was a source of strength, a salve. Though I may always bear the marks of those wounds, there is some peace, some ease (as you call it) in knowing that I am not alone, and that the journey through isn’t a walk I have to face by myself. Their stories, their spirits, are always in the work and in me, and that truth has made it easier to wade through the witnessing and writing.

Still, this truth doesn’t negate the pressure a writer feels when trying to tell a story that involves the pain and suffering of others. One theme that percolates in both our books is the tendency to lean on prayer and faith and ritual as a way to find understanding, joy, healing. How do you think these things inform your work, and how has attempting to reclaim them influenced who you are as a person and writer?

What strikes me about this question is how prayer and ritual function as what Fred Moten calls “spiritual technologies”—systematic practices that enable not just survival, but a form of cultural transmission that refuses erasure. In Yoruba cosmology, there’s this concept of ori, which encompasses both the physical head and what scholars like Ayodeji Ogunnaike describe as our “celestial self” or spiritual double. When I write, especially about Damola and the disappeared, I’m not just documenting loss—I’m performing a ritual that connects my ori òde, my physical self, to the ori inú, that transcendent dimension where the ancestors dwell.

Prayer, for me, becomes a way of consulting what my grandmother would have called “the head”—seeking guidance from forces larger than my individual consciousness. These aren’t Christian prayers, necessarily, though they borrow that language. They’re more like incantations, attempts to invoke àṣẹ, that life force that Yoruba tradition tells us “regulates all movement and activity in the universe.” When I light candles before writing, when I pour libation, when I call on the names of the missing—these aren’t just aesthetic choices. They’re technologies inherited from people who survived the Middle Passage by refusing to let their spiritual practices die. Writing becomes a form of ancestral consultation, a way of ensuring that what I’m putting on the page honors not just the living, but the dead who refuse to stay silent.

I love thinking of writing as an “ancestral consultation!” In both of our books, the act of trying to connect with our ancestry is what leads us, in some ways, not to answers– but to understanding and healing. I’m hesitant to say that poetry itself is the solution to grief, so much as it is the act of being brave enough to do the questioning, the seeking, that leads us to a kind of salvation that can help heal the intergenerational wounds we speak of. Poems, perhaps, are simply the container, the vessel, through which these excavations occur– but I believe it’s the journey of making the poems, of dealing with one’s self and history that I think ultimately unlocks the door to reclamation. If we can find in us enough heart to go there, to do the heavy lifting and still find a way to breathe, that is where healing can happen.

Yes, Isabella, I agree with your framework. I think, in some way, very often, Joy Priest’s scholarship and exploration of the black outside suggests new, old, and imminent ways by which black writers can escape this chaotic world, or even ourselves. Poetry does that, you know, offers an entrance into a world we build for ourselves—that alternates the truth while also not departing from it. Finding poetry when I did altered my destiny. I was moving in the world, unsure of what was happening, unsure of who I was, totally blindsided by my own memories, shut out of my childhood, and the abuse I experienced from older women. In Nigeria, a church called RCCG holds a Tuesday service called “Digging Deep,” where they study the Bible, similar to Sunday School. Poetry is my closest analogy; it involves digging deep into your soul, searching for an oasis. Coming to the fullness of self, arriving at what is finally the ultimate truth of self and the awareness of, or the fullness of memory, is healing for me. A form of healing that people never really declare is “safety,” and poetry is where you come to when the world feels unsafe, the outside of a burning house, the boat you find in a storm, the ark Noah built when God flooded the world. This reminds me of some of the oral traditions in Yoruba culture, particularly incantations, which are the poetry of “power.” By conjuring certain words together, often with proverbs, mythmaking, and invocations, our fathers, past and present, arrived home safely from war, survived or escaped danger, became wealthy, healed the sick, called water out of a rock, and stopped rain. So I agree with you about the journey, the process, but poetry meant a means of being for the Yoruba people, so something had to give. Even David in Psalm 119:105 said the word, which was synonymous with the Son of Man, in the gospel of John, as the way, the truth, and “life” as that which “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Poetry, word, is a miracle, the means of this miracle, the result of the miracle.

I am in awe of the title of your collection, Someone Else’s Hunger. Could you kindly walk me through the collection, from arriving there to what you were contending with or navigating, and how you decided or arrived at something that empowers or identifies hunger as someone else’s? I think we were designed to be hungry, feral, needy, but at what point does this hunger become ours or someone else’s? Is it given or taken? Forceful or kind? I keep going back to moments in your book, for instance, in “I dream of Havana” where you say “Abuela has taught me / to open wide as / Windows” and I wonder if, similar to African tradition, this hunger is something we were taught to give? Is this harm or care?

I love thinking through all this with you as I recently discovered that one of my great-grandparents from Cuba was 100% Nigerian, and one of my grandparents also 100% Spanish. This isn’t surprising because many Afro-Cubans are the descendants of Spanish colonizers that raped their African slaves. When I think about my history with assault and hunger, I think of my Cuban ancestors who also suffered this same kind of harm– though it isn’t lost on me that the consequence of that harm is my life, which is why I’m so intentional about wanting to make something worthy from that wreckage. When I was trying to title the book, it wasn’t immediately clear to me that hunger was the throughline– but I understood very early on how violence begets violence. And what drives violence? That’s the question I kept returning to. Where does all of this pain come from? What I’ve landed on is the belief that there is a physiological impulse in all of us to do what we must to survive, and the best name I have for that bodily and spiritual drive is hunger. Hunger is the body’s signal that we want to live, that there is a need that needs to be met, that we must take action. But hunger can quickly transform and more dubiously, become the catalyst for taking, hurting someone else. It’s sobering and grounding to remember that all of us will be hurt and hurt others; that’s life. In this book, hunger has many different manifestations. The hunger of my ancestors on the island I’ll never know as home, the visceral hunger of my body when I suffered from anorexia and bulimia, the hunger we all carry with us as we chase the life we want to make. I think the main work of this collection is sifting through the different faces hunger has, and trying to understand how all our hungers and histories imbue our future selves and the lives of one another.

Isn’t it wonderful that the truth about you and your lineage is coming at a time you are having a conversation with a Nigerian writer? As I write this, I am listening to Bon Iver’s “Speyside,” where they say, “It serves to suffer, make a hole in my foot / And hope you look,” which expressively and sonically describes my conversation about creatives and how we display this hurt beneath the skin. Over and over again, I go back to specific lines in your work where you are either holding on to or running from the figures that claim from the personified “I.” How wonderful, craftful the music of your book is—how devastating, like Bon Over’s music, the music in your book is. We will always carry the self with all its hard damage, the familial and the collective, and like I have mentioned earlier, our work is now a documentation of our existence within history. That grandmothers survived so we could remember for them, that mothers wept and prayed, that fathers and their tough loves persevered. We are collectors and we are doing the job of recollecting and therefore reclaiming. We are presenting a version of truth that perhaps no one will ever present in the same way we have. I am, we are, the scar, the proof, a testimony. How lucky we are to have language to help leave our marks on this world.

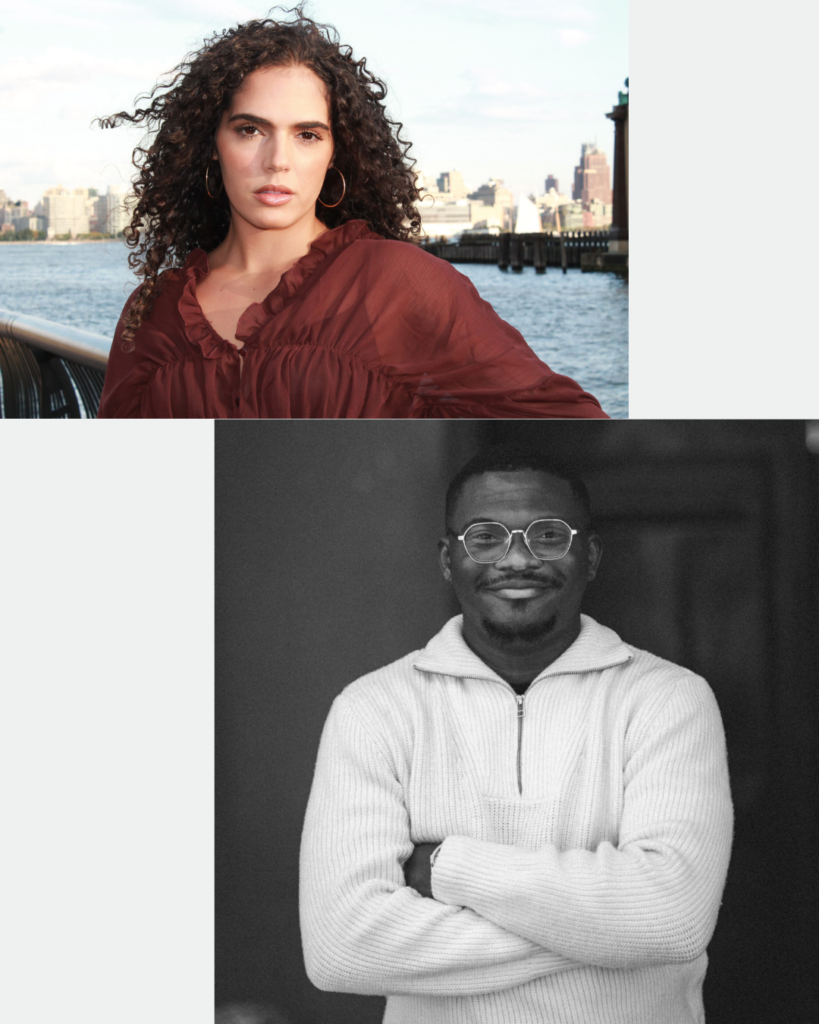

Adedayo Agarau is the author of The Years of Blood, winner of the Poetic Justice Institute Editor’s Prize for BIPOC Writers (Fordham University Press, Fall 2025). He is a Wallace Stegner Fellow ‘25, a Cave Canem Fellow, and a 2024 Ruth Lilly-Rosenberg Fellowship finalist. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Agbowó Magazine: A Journal of African Literature and Art and a Poetry Reviews Editor for The Rumpus. He is the author of the chapbooks “Origin of Name” (African Poetry Book Fund, 2020) and “The Arrival of Rain” (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2020). Adedayo currently lives in Oakland, CA.

Isabella DeSendi is a Latina poet and educator whose work has been published in POETRY, The Adroit Journal, Poetry Northwest and others. Her debut poetry collection titled Someone Else’s Hunger was published by Four Way Books. Her chapbook “Through the New Body” won the Poetry Society of America’s Chapbook Fellowship and was published in 2020. Recently, she has been named a New Jersey Poetry Fellow, a Ruth Lilly Fellowship finalist, a finalist for Rattle’s $15,000 Poetry Prize, and was included in the 2024 Best New Poets anthology among other awards. Isabella has attended Bread Loaf Writers’ Workshop, the Storyknife Writers’ Residency in Alaska, and holds an MFA from Columbia University. She currently lives in Hoboken, New Jersey.

This post may contain affiliate links.