[The Song Cave; 2025]

“‘You would never listen to me and now look what happened!’ Mama fainted dead away. The next thing I knew I woke up with my leg gone.”

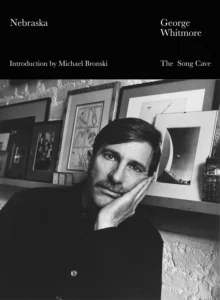

So begins Nebraska, the final novel by George Whitmore. Published in 1987 by Grove Press, it has long been out-of-print, and is now being republished by The Song Cave. The opening is a collar-grab, and the following pages don’t let up. In 1956 Nebraska, as flat-ass nothing a time and place as one can conjure, Craig Mullen, the 12-year-old narrator, has been hit by a car and had his leg amputated:

I was in and out. I lost whole days. I heard Mama saying “We’re going to be paying off the bills for the rest of our lives.”

A world is sketched out quickly. A sensibility, too. Told with the blunt force of Linda Manz’s voiceover in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (minus the outer borough accent), Whitmore’s narrator has the dissociative quality of an outsider, someone who has already clocked too many hours in fear. It’s the voice Bob Dylan sang “I Was Young When I Left Home” in. Though Craig hasn’t fled yet, there’s a sense he was never completely there. A ghostliness. He’s a kid who bolts across streets without looking, who forgets groceries on his errand run and has to return to fetch them, whose mind is elsewhere. But Whitmore doesn’t make Craig out to be a dreamer. He’s tamped down. Is Craig a mordant futilitarian or is this the clip-winged taciturn factory setting of a Midwestern boy taught that acceptance and stifling emotion are synonymous? Is there a difference?

Craig’s father was a drunk who abandoned the family, a blessing that still left a hole. His mother and sisters care for him. The days don’t progress or unfold. There is no forward-looking, no opening up. The momentum is the next day, not so much a future as a planetary movement—night matches mood, sun interrupts, and another day begins. Then his Uncle Wayne arrives home from the Navy, energetic and voluble with plans. He lights up the grimness until he’s busted in a bus station’s bathroom for lewd conduct and it’s revealed he was dishonorably discharged for being queer.

This all seems on track for a particular kind of heartless heartland coming-of-age tale, but Whitmore muddies it at every turn. Wayne is falsely accused of molesting Craig and institutionalized. The drunken dad returns sobered-up and crazed with born-again Christianity to rescue, or kidnap, his son. A carnival mirror Huck Finn bend. The book gets darker and stranger. 1957 then jump-cuts to 1969. There is tragedy and something like grace or a truce, some small understandings are made. I never forgot the ending from when I first read the book in the early 1990s, and it still got me good.

Whitmore’s Nebraska has been compared on Goodreads (our stand-in along with BookTok for literary cultural criticism) to Scott Heim and Dennis Cooper. While these are serviceable comps in that loose algorithmic math—Heim’s exquisitely strange and wholly underrated We Disappear comes to mind at moments, and Cooper’s pared-down prose and teenage characters—they mostly seem a matchy-matchy “this gay writer reminds me of these gay writers.” Whitmore is an older voice, one that stretches from Southern Gothic—Carson McCuller’s scorned Miss Amelia parting the curtains to peer down—to the delicate-healthed dissociative narrators of Denton Welch to the perversity of James Purdy (the more apt gay writer Match Game winner).

On June 16, 1991, Edmund White published “Out of the Closet, Onto the Bookshelf” in the New York Times (Sunday, Late Edition – Final) on “the evolution of the gay male novel.” As an author who fast-tracked its progression with his novel A Boy’s Own Story, White has plenty to say with authority, cut with his trademark verve and honesty. He lays out his own homo-lit education beginning shabbily in the early 1950s as a curious teenager at the public library in Evanston, Illinois (Death in Venice by Thomas Mann and the biography of Nijinsky by his wife) and ranging across the foundational classics: Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man; Andre Gide’s If I Die; William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch; John Rechy’s City of Night; and Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers. He maps the beginning of the new (American) gay novel to 1978 with the publications of Larry Kramer’s Faggots and Andrew Holleran’s Dancer From the Dance, and into his own circle of writers, “a casual club named the Violet Quill” who met once a month in each other’s apartments starting in 1979. The group was comprised of Felice Picano, Andrew Holleran, Robert Ferro, Christopher Cox, Michael Grumley, and Whitmore. Vito Russo, who wrote the foundational homos in Hollywood tome The Celluloid Closet was an occasional visitor. In 1983, White moved to Paris, and he writes:

When I came back to the States in 1990 this literary map had been erased. George Whitmore, Michael Grumley, Robert Ferro and Chris Cox were dead; Vito Russo was soon to die. Of our original group only Felice Picano, Andrew Holleran and I were still alive; better than anyone else, Holleran has captured the survivors’ sense of living posthumously in his personal essays, “Ground Zero.” Many younger writers had also died; of those I knew I could count Tim Dlugos, Richard Umans, Gregory Kolovakos, the translator Matthew Ward and the novelist John Fox (who’d been my student at Columbia). My two closest friends, the literary critic David Kalstone and my editor, Bill Whitehead, had also died.

For me these losses were definitive. The witnesses to my life, the people who had shared the same references and sense of humor, were gone. The loss of all the books they might have written remains incalculable.

That cultural crater underlies much of my reading and writing. The what if that leads nowhere but to a sense of duty that sometimes feels like the Japanese soldier Hiroo Onoda who famously didn’t know World War II had ended and remained on Lubang Island in the Philippines, continuing to fight as a Japanese soldier until 1974, nearly 29 years after the war’s conclusion (of course, are wars ever over?). The exhuming of some of these long out-of-print authors is being carried out by publishers like The Song Cave, Pilot Press, Nightboat Books, Fellow Travelers Series from Publication Studio, and Archway Editions which recently republished Christopher Coe’s Such Times.

Whitmore was forty-three years old when he died in New York on April 19, 1989, from AIDS-related complications, two years after the publication of Nebraska. It’s hard not to wonder at what he would have written if he’d lived. Hard not to make the calculations. As it is, he wrote a classic queer book that has fortunately been given a new life and retains all its powerful weirdness.

Nate Lippens is the author of the novels My Dead Book and Ripcord, both published by Semiotext(e) and in the UK by Pilot Press. My Dead Book was a finalist the Republic of Consciousness Prize UK in 2023. His fiction has appeared in many anthologies, including Pathetic Literature, edited by Eileen Myles.

This post may contain affiliate links.