[And Other Stories; 2025]

Banu Mushtaq’s short story collection, Heart Lamp, is set in the southern Indian state of Karnataka, where Mushtaq is from, and features women who have in some way been disappointed or abandoned by their husbands. While there is a range to these men’s failings, Mushtaq points to a common point of origin: a society that allows men to do whatever they want without answering for the consequences. The story “Black Cobras,” for example, centers on Aashraf, whose husband has left her and her three daughters to marry another woman. Yakub, the husband, wants a son to whom he can pass on his autorickshaw business. He harangues his wife when she asks for money to buy medicine for their sick baby: “You pop out an army of girls and roam around like a dog. Learn to have a little bit of decency at least.” He says, “If you who squats to pee has this much arrogance, how much arrogance should I, who stands to piss, have?” He kicks Aashraf, causing the baby to fall out of her arms and die.

As if all this suffering wasn’t enough, the mutawalli saheb, tender of the mosque, does nothing for Aashraf. She and her three daughters spend the day waiting for “her judgement” sitting on the mosque’s floor in the rain, as word travels among the women and girls of the town. Instead of judging Aashraf like the men do, Mushtaq turns a sharp eye onto Yakub and the mutawalli by using a capacious omniscient narration, allowing us into most of her characters’ thoughts. When the mutawalli first sees Aashraf as he enters the mosque, he thinks more about where and how to spit the paan juice that “had accumulated in his mouth” than about the woman’s grief. After hearing Aashraf’s tragic story, this concern is strikingly shallow. One of the most inventive and profound aspects of Heart Lamp is how Mushtaq layers these multiple points of view: in “Black Cobras” alone there are at least six, most of them the perspectives of women and girls. A few stories are told in the first person, but most of the time the close third-person narrator moves between those who have all the power and those who have none.

In addition to the patriarchy, Mushtaq turns her attention to the caste system. In “The Shroud,” a higher caste woman, Shaziya, promises to buy a kafan dipped in holy water for her servant, Yaseen Bua, on her Hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca. In order to pay for the kafan, Yaseen Bua takes money from her savings for her son’s wedding. Afterwards,

she began to feel as if she had stolen it from someone else. She could not shake off her immense guilt, she became restless, and for three days tied the money to her seragu and protected it. But even her maternal instincts could not defeat the intensity of her private dream.

After Yaseen Bua gives Shaziya this money to buy the kafan, Shaziya puts the money near the sink and thinks, “Money from the pockets of poor people was, just like them, broken, shattered, crumpled, wrinkly, diminished in essence and form.” She immediately forgets about the money and her promise.

Like the point of view shift from Aashraf’s sufferings to the mutawalli’s paan juice in “Black Cobras,” the juxtaposition between Shaziya’s and Yaseen Bua’s perspectives at this moment is heartbreaking. The intensity of Yaseen Bua’s desire for the kafan is made more poignant because of how little she has and what she will sacrifice for the gift; this intensity is cast aside by someone who has enough money to make Yaseen Bua’s sacrifice seem inconsequential. The narrative risk with this abundance of points of view is that they can get confusing, especially at the beginning of a story. Sometimes this kind of prose style can feel gimmicky or obvious. But Mushtaq manages to elude these problems by building characters who are complex and surprising. Though I never sympathized with Shaziya (or the mutawalli in “Black Cobras” or the other husbands), I did laugh at her passion for shopping that she justifies by being on Hajj.

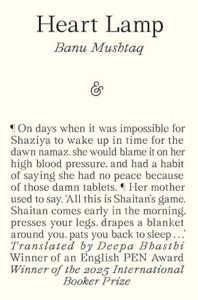

Heart Lamp is Mushtaq’s first collection translated into English and was compiled by her translator Deepa Bhasthi from six short story collections written in Kannada between 1990 and 2023. It is the first book originally written in Kannada to win the International Booker Prize. Mushtaq spent her career as an activist and lawyer in the southern Indian towns where these stories take place, and her storytelling draws from an oral tradition that mixes dialects and languages. Bhasthi’s translation captures this unique linguistic texture by occasionally using the original languages. As she points out in the translator’s note at the end, titled “Against Italics,” “this code switching between the three-four languages we engage with daily results in a delightful mix of Kannada, Urdu, Arabic, Dakhni and a Kannada as spoken by specific communities in specific localities of the Hassan region.” Bhasthi’s translation includes interjections like “Che!” and “Arey!” and the text is peppered with transliterations and Kannada and Urdu words. Though I was always conscious of reading a translation, the English version is a vibrant and dynamic experience in its own right.

In an interview on The Booker Prizes website, Banu Mushtaq answers a question about inspiration: “My heart itself is my field of study.” As a lawyer and activist, her heart was often exposed to the accepted injustices of gender and caste. Through fictionalizing these women’s stories, Mushtaq strips down people in power and exposes their ugliness: their ego, selfishness, narcissism, and heartlessness. These features of Karnataka society echo everywhere; here in the United States in 2025, we are daily exposed to another lesson about what bad behaviors will be excused just because a man is a man and rich. The happy-ish endings of Heart Lamp come when the powerful are humbled and the powerless are avenged: Shaziya is crippled by guilt after Yaseen Bua dies and the mutawalli saheb in “Black Cobras” receives a string of curses from the women of the community and allows his wife to have the hysterectomy she has been asking for. These characters, at least for a time, have been forced to change their hearts.

Amber Ruth Paulen is a writer and educator living in rural Michigan. She earned her MFA in fiction at Columbia University and is currently writing a multi-generational novel-in-stories. www.amberpaulen.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.