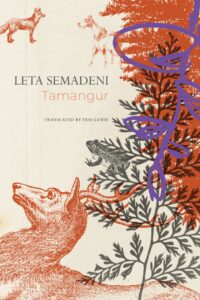

[Seagull Books; 2025]

Tr. from the German by Tess Lewis

The story begins like a fairytale: a young child lives with her widowed grandmother in a tiny village somewhere in the mountains. They are surrounded by animals, trees, and snow. We never learn their names or the name of their village, or if they even have names. From this simple beginning, the story picks up details, taking on the contours of realism, even of mundanity. They cook and eat meals together, talk with their neighbors, celebrate holidays, recount dreams, and tell many stories. While they occasionally run errands in town or venture across the nearby border, they mostly stay home—the kitchen, the bed they share, and the other living spaces of the grandmother’s house. They also come in and out of contact with the village’s eccentric residents. There’s a friend who believes she’s in a relationship with Elvis, a distant relative who’s convinced she’s being followed by murderers, and a seamstress who steals people’s memories. The child and her grandmother laugh a lot and share many happy moments, but as each day slips into the next it becomes gradually more apparent that something is missing. In their secluded lives, the grandmother feels the weight of repetition and boredom, the sense that everything is happening somewhere else or in a different time—above all, in her memories. The grandmother is dissatisfied with her lot, calling their Alpine village “a flyspeck on the map.” And we slowly discover much darker, more painful events from the past that explain why the child and her grandmother have come to live together in their sleepy, backwater village.

Originally published in German in 2015, Tamangur is Leta Semadeni’s first novel. She already had poetry collections and children’s books to her name and has since published more poetry and a second novel. Tamangur won the Swiss Literature Prize in 2016 and in 2023 Semadeni earned Switzerland’s prestigious Grand Prix for Literature for her entire body of work. Beginning with her early poetry, she has written in both German and Romansh, a Romance language with around 40,000 speakers and one of Switzerland’s four national languages. Like many Romansh speakers, Semadeni grew up using an idiom of Romansh, Vallader, at home and learned German at school. She now considers Vallader her “mother tongue” and German her “first great love.” While Tamangur was written in German, her poetry collections are bilingual, and she translates her poetry between the two languages.

Semadeni’s close attention to language and her lyrical skill are apparent in Tamangur, thanks to the work of Tess Lewis, an established translator of German and French literature. Unfolding in eighty-four vignettes, ranging in length from a single paragraph to a few pages, Tamangur often reads like a collection of prose poems. It eschews linear storytelling in favor of a more associative mode that drifts between characters’ memories, their dreams, their conversations, and their actions while evoking the novel’s alpine setting with icy clarity:

Light from the streetlamp flickers through the fitful gap between the curtains and falls onto Grandmother’s face, which looks like she has slipped out from behind it.

The sound of a cow lowing comes from outside. As does the sound of the neighbor’s cows shifting in their stall. The way they tilt their heads sideways and, with wide-open eyes, lose themselves in dreams of grass and their companions’ rough tongues.

The wind runs riot through the fresh snow, the world looks transformed. Inside, everything is different, too.

The cow lowing, the other cows shifting in their stalls, their tilted heads and rough tongues: the novel displays a remarkable precision of detail and awareness of the characters’ natural surroundings. Semadeni creates a poetic, dreamlike landscape that feels real, even as it avoids any mention of Switzerland or historical events, making the novel’s characters and setting seem a bit abstract at times.

With the compact force of a poem, the novel gains much of its power in what it does not say. We’re never explicitly told why the child’s parents have abandoned her, but it seems to be because they hold her responsible for her younger brother’s death. The child is haunted by this traumatic event: images of water and the river where he drowned recur throughout the novel. Mystery also surrounds the child’s grandfather, who has recently died. We’re told that he has “flown the coop” to Tamangur, a paradise for hunters’ souls. The child and her grandmother frequently mention Tamangur but leave it mostly unexplained, speaking of it in a matter-of-fact way, as if the grandfather had merely gone off for a hunt in the woods. At the beginning of the novel, I wasn’t sure whether he was really dead or alive. Their conversations involving Tamangur have a kind of overheard quality, with the novel constantly shifting between closeness and distance, familiarity and strangeness.

The novel is a portrait of growing up and growing old, twin phenomena that run in the same direction yet seem somehow opposed. Its focus on childhood and old age reminded me of Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book, which also follows a young girl and her grandmother living together in a remote region. Semadeni skillfully evokes the curiosity and playfulness of a child’s point of view while also grounding that perspective in a precocious wisdom:

As she climbs the stairs, it occurs to the child that her grandmother is always trying to put one over on ageing. At night she grimaces at the mirror and laughs at her image […] This makes the child snort so much that she has to hide under the covers and kick her feet. Then Grandmother has to laugh for real. She tickles the child’s feet until the two of them are exhausted from laughing.

The child and her grandmother often fall into laughing fits like this one; these moments bring a childlike levity to the novel’s heavy themes of aging and death. These themes are also bound up with the body and sexuality. The child gradually learns about sex—though, for her, it still happens at a distance. In one vignette, for example, the child and a friend peek through a hole in a wall at the local tavern, gazing into a room where a couple are having sex. Tamangur is more interesting, however, for how it portrays sexuality, beauty, and the body from the perspective of old age. The grandmother often examines her naked body, particularly her breasts, and has tangled feelings about what she sees, wondering whether she is still beautiful when she is no longer young. At other times, she takes pride in her body: “I still have a lovely chest.” Her complicated feelings are part of what makes her the novel’s most compelling character.

Tamangur is suffused with longing: for places, times, and above all people who are gone. Even the characters’ pet dog, we’re told, dreams of sausages, of fat roasts and cutlets, and of love. But nothing is really gone. As one character says, “It’s always the absent things that take up so much room.” Tamangur manages to feel both sparse and full, its careful and restrained prose revealing how the seemingly mundane lives of its characters are ready at any moment to burst into something else. This makes the novel’s characters, for all their eccentricities and their lack of names, entirely recognizable. In depicting a relationship between characters at opposite ends of life, the novel examines the particularities of loss, longing, and joy at different ages while showing how, like a fairytale or legend, these experiences and emotions are shared across generations.

Noah Slaughter writes fiction and essays, translates from German, and works in scholarly publishing. He lives in St. Louis.

This post may contain affiliate links.