[Algonquin; 2025]

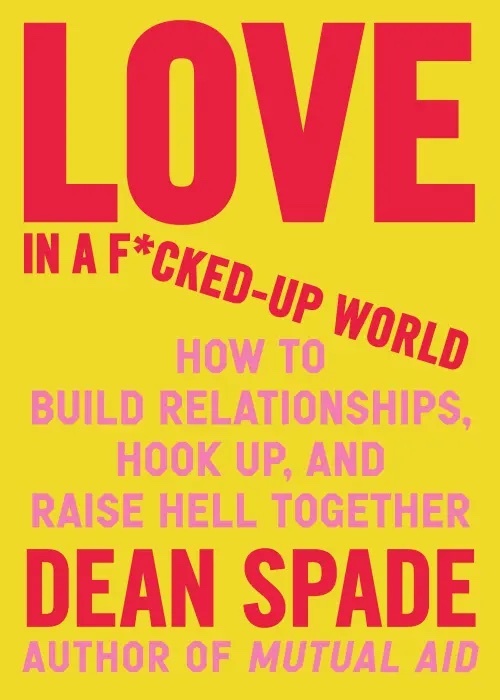

In my dreams, lawyers are some of the best people to ask for advice on love, because being good at arguing means you’re good at loving. Writing strong compound complex sentences means you know when to simply say “anyway,” too. Sometimes my dreams are also my lived life, and other times they are not. Dean Spade is a lawyer, and the author of Love In a F*cked-Up World (which I’ll abbreviate as LOVE, because LIAFUW sounds like an athletic league), as well as two previous books, Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law (Duke UP, 2015) and Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next) (Verso, 2020). Spade has many other identities besides these, too. On the book jacket, he (or perhaps Algonquin, it’s hard to tell) calls himself “a leading voice for trans liberation, prison abolition, and mutual aid.” Okay, so what does love have to do with that?

To begin, Normal Life was a critical text for me as both a dissertation-writer and administrator, and I’ve taught the first chapter of Mutual Aid in nearly every class since the book’s publication. My point isn’t that I am some kind of Spade Book Wizard, but that I have walked with his work for years now, in classrooms and streets, and used it and returned to it, and so it matters to me as part of my life’s map. Most significant was the definition of power Spade introduces in Normal Life. For him, power is not a matter of individuals or institutions so much as “interconnected, contradictory sites.” In this way, we learn to zoom in on not so much who is being targeted (and woof, could we write that list), but the existence, and reification, of “norms that distribute vulnerability and scarcity.” For example, cash bail. For example, Sodexo contracting with schools, stadiums, and prisons. Perhaps especially, ICE coming for Mohamed Sabry Soliman’s wife and children. The fact that these situations can be argued as fair and equitable (not by me, obviously) is ultimately part of their violence.

To be real, and precisely because his earlier books really thwoked me in the heart, I was wary about what I saw as Spade’s expansion, beyond the fucked-up world to love. Obviously this was my problem, and if I had a little money for every activist who used reading bell hooks as a way to dismiss consent or Jessica Fern as a way to dismiss commitment, I would have more than a little money. I realize I’m talking about myself a lot so far, but I’m not the only person who has experienced these dynamics and keeping it personal keeps me from scapegoating anyone. Too, though, I know to be wary of the punk kid Puritan parts of my brain, and to check myself when they show up. Can Dean Spade write about love? Of course, and while my initial side eye is valid, it also shows just how badly a book like this is needed, today, and especially as connected to a wider liberation project.

LOVE “dares us to decide,” writes Spade, that “romance is not separate from our politics of liberation and resistance.” This is not separate from RuPaul’s now-ubiquitous refrain about loving yourself to love somebody else, but because it starts with an active dream of freedom, frankly it means more to me. Love others, they will help you love yourself. This dovetails too with Tricia Hersey’s Rest Is Resistance (Hachette, 2022). “Treating ourselves and each other with care isn’t a luxury,” she writes, “but an absolute necessity if we’re going to thrive.” At the end of the day, we must dare to decide there will be another day, and as it turns out, coming correctly really is ultimately about care and ease. It is very hard to work together towards emergent capacity when your vagus nerve is lit up like the Drop Tower at Lakeside Amusement Park. “To me,” writes Spade, “LOVE is a clear extension of the questions at the heart of my previous work: How do we build lasting and effective resistance movements? What are the barriers, and how do we overcome them?” LOVE is more of a workbook than the earlier two texts in what I’d argue is a trilogy, but this is radically appropriate if we are all to have this conversation truly and together.

The paperback is a perfect size (5’’x7’’) and color (stoplight yellow) for reading on subways and at the bar, and the text itself has five main sections, covering dominant culture’s scripts, numbness and temporary highs, the romance cycle (aka “falling in love and losing your mind”), fear and courage, communication and repair, and finally, “revolutionary promiscuity.” Such phrases (“dominant culture”) can be dissociative, or signal virtue when morality actually isn’t at stake, but at the same time, do I wish I’d learned about romance cycles along with menstrual cycles? Absolutely.

I also wish LOVE considered somatics more, in particular the effects of PTSD on love at home and outside it, but again, this is a wish not a criticism. I loved halfway through, when Spade paused to clarify that this book is about “how to develop emotional skills,” specifically ones that support our capacities to feel, understand our reactions, choose, and build. He asks directly to “please not weaponize the ideas in this book,” and uses harm reduction frameworks throughout, clarifying being on autopilot, high, or numb as states, not diagnostic, systemic, or to be condemned. I also loved how Spade describes patterns, especially in relation to technology and freedom, which is part of the abolition conversation I want to have. At one point, he mentions a friend who talks about “a men’s room” “in her head,” meaning not a place to piss but a part of her brain giving attention to romantic interest or shrinkage. This boundary, this loss, is also one occupied by Jpay’s “variety of corrections-related services,” SNAP, so many asynchronous education interfaces, and Tinder, and I loved that Spade didn’t trash it, because it exists. I loved that he kept listening and said his friend felt “immense relief” when she “finally started to leave it empty.” The separation from mental habits and settings gave her clarity, and while I realize one can’t leave Jpay nearly as easily as Tinder, the potential for freedom remains. Similarly, Spade’s chapter “Falling In Love” ends with a section on breaking up with lovers (breaking up, not how to break up; it happens), and specifically a couple who included acting with compassion and integrity in their ketubah, should they choose to separate. Staying only if you want to is “truly loving,” Spade says, and besides Nina Simone telling Peter Rodis that “freedom is no fear,” this is the truest kind of liberation I know, so far.

Could this book have spared me pain, had I read it in my twenties and thirties? Maybe, but avoiding pain isn’t the point. Like its predecessors, Normal Life and Mutual Aid, Love in a F*cked-Up World helps us (and I do mean us) have the conversations we need to accept change, trust love, and be together. Given my own healing path, I bristle at some of the Final-Girl language about the impacts of our (meaning, humanity’s) dependence on extractive systems (“It’s all so bad, and it’s about to get so, so much worse”), but admittedly this is language I embraced before I realized it kept me from imagining a future. That is a fact about my brain, and maybe not yours. We do need all of us. Ultimately, this book, and Spade’s others, are ones I want to read and discuss with everyone I already love, and every lover I have yet to meet.

Mairead Case lives in Denver. (maireadcase.com)

This post may contain affiliate links.