[Semiotext(e); 2022]

Note on form: My conscience suffers from scrupulosity. In the case of reviewing this book, especially because of the madness and outright wickedness of the subject (or so my conscience perceived him), I ran up against the tremendous difficulty of being “objective.” That noble dream. The choice to speak from the below perspective was a ruse, initially concocted after several failed attempts at a more conventional review, to get around the specific illusion of the authority of the reviewer. I was incapable of the posture of authority that requires a certain level of disinterestedness because of my broken conscience.

Roughly 90 percent of Harry Smith: American Magus consists of transcribed interviews—many of them between the editor and acquaintances of Harry, and one between a magazine editor and Harry himself. To made my own contribution to the flow of this dialogue, I was compelled by something more obscure than “creativity” to add another voice: the fleeting sounds out of our mouths that Harry fastidiously curated.

I think Harry would be happy to see his secondary literature as ephemeral and diffuse as possible given his commitment to fragility (or did fragility choose him?). To verify such a claim, I suppose the reader will have to try the book for themself.

Come on, Dane—you got yourself into this, you can get yourself out. Houdini. You’ve said he’s your spirit animal. Stand on that—though calling him an animal is probably not right.

You’re too anxious with this whole thing about calling good evil and evil good. You need to think more in terms of Eileen Myles’s maxim: There’s nothing moral about literature. Was that from Inferno? For Now? In what way is the publication of Pathetic Literature a boon for the publication of Harry Smith? That’s a good hook. You could run with that. Being trapped by Flanagan’s story in Pathetic about eating shit.

What was Colin saying about the book you read years ago, about autocoprophagia? You told him it was a chapter in Globes (Peter Sloterdijk, Semiotext(e), 2011). He said no, that wasn’t it, and he would know because you talked to him so much at that time about Peter. So what was it? Is it possible that you black out on entire books, or portions of books?

This is all related to that scene last year in the acute psychiatry wing at the Long Beach VA. You’re still paranoid about it. TV on in the middle of the night when you couldn’t sleep, half a dozen patients sitting in the TV area. The Tibetian-sounding deep throat chant as a man climbs up out of the coffin he was locked in, black leather skull cap pulled down over his eyes, a black gag ball strapped into his mouth. Some kind of hell. And what did you do? You thought that it was you on the screen. You shuffled into the bathroom and meticulously pulled the gagger out of your mouth. In the mirror, you saw nothing actually there, but it released a stabbing tension in your jaw.

You could say something about that hell, the deception that goes all the way down when you’re living the way you were living. The drinking. You probably think you’re better than Harry because you think you didn’t hurt people when you drank, the way he hurt people. You probably think that, don’t you! You might hide feelings from your conscience for a time, but let me remind you that what is done in the dark will all come to light.

So to do this right, you’re going to have to confess to some things. The feeling you get when you read about the occult, for example. Nobody is going to like that, but you’re going to have to if you want to be honest. Self-Portrait as the Devil. I mean, come on! Maybe you just start by saying that you don’t like Harry. Ya, that’ll work.

Yet there is something so likable about Harry in his own voice. Simple and matter-of-fact. In a rare interview from 1968 with the folk artist John Cohen, reproduced in Part 2 of the text, Harry comments on his mode of operation: “I haven’t wanted to do anything that would be injurious. It’s very difficult working out a personal philosophy in relation to the environment. Consistently I have tried different methods to give out the maximum.” So gentle. It was Harry as told by his friends that was so dislikable. One of them suggests a fierce and wrathful mask disguised an otherwise tremendously loving man. That seems to check out, and you’ve got to give him the judgment of charity—maybe he was just in a lot of pain. Maybe he just wanted to fly away—one interpretation of his paper airplane collection.

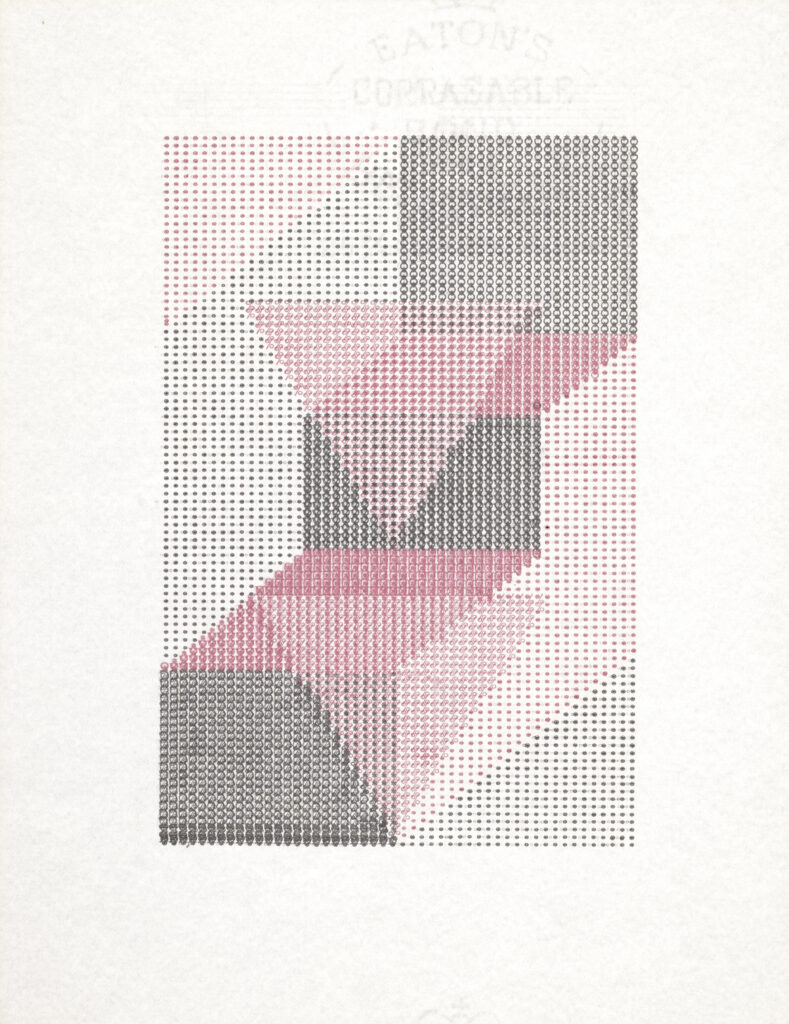

At some point you will have to provide a bit more depth. What about the typewriter drawings, the three of them? Though Harry’s friends discussed many of his other works, often with great enthusiasm, especially the stills from his experimental films and the paintings based on live jazz performances, none of them had anything to say about the typewriter works. In fact, they seem to float, existing in isolation from the rest of the text.

First one, ca. 1970–1972. Not even sure from the image in the book which key he would have used to make the marks, and having never used a typewriter, what would have gone into positioning the paper, etc. Would have been an amazing task.

First one: appears to have ten separate layers, though counting accurately is complicated by the visual effect of the markings. The layers: four triangles, two rhombi, three rectangles, but again the way they are layered, the categorizing is confused, and those don’t add up to ten. Is there something here about the scholastic antepraedicamenta—the work resisting simple predication? In the preface, the editor admits to the limited scope of the book, which could always only scratch the surface of “the systematic flowcharts of [Harry’s] various enquires,” that “[urge] life to create itself.” This dubious claim to autogeny is related to the typewriter drawings one way or another, because in Harry’s world everything is related to everything else, which is why the editor’s mention at the end of the preface of the labyrinth of Harry’s oeuvre leads back to a kind of immanent geometry—a calculus of wonder. Would Harry have enjoyed Borges? Think so.

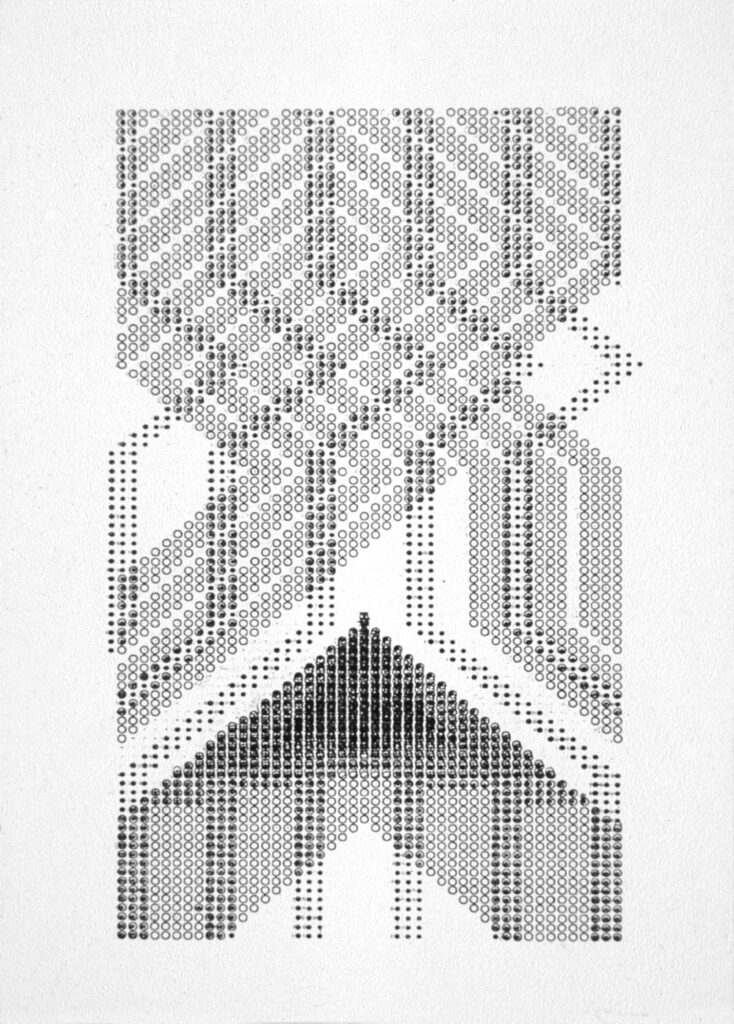

The second and third, ca. 1980. That these images come from the Harry Smith Archives, when so many of his other works he destroyed or misplaced, that he held onto these three works specifically—was there some valuation happening? That they survived the inexplicable fire in Dr. Gross’s apartment where Harry was storing his work (you better check on your own boxes in Norm’s closet). The second typewriter drawing, more quilt-like in the style of Harry’s collection of Seminole quilt patterns. The mark here is clearer—a plain circle, perhaps the O key, some of which are filled in with a solid black dot, perhaps the period key. Five darker columns run vertically through the upper two-thirds of the composition with parallel triangular segments halfway down, then run off the sides of the paper. Behind these darker lines, a lighter variegated field of rows, four O’s thick, running at roughly forty-five degrees to the darker columns at most of the intersections. The depth achieved by these two elements is astounding when one thinks of the flat quality of what a typewriter normally produces. The bottom third composed of an even darker triangle with its vertex pointing upward. The marks here must have been repeated very carefully because there are still thin blank lines cutting vertically through the triangle between the elements of each mark. Running down below the hypotenuse, again five darker columns that align with the five of the same from the top of the composition.

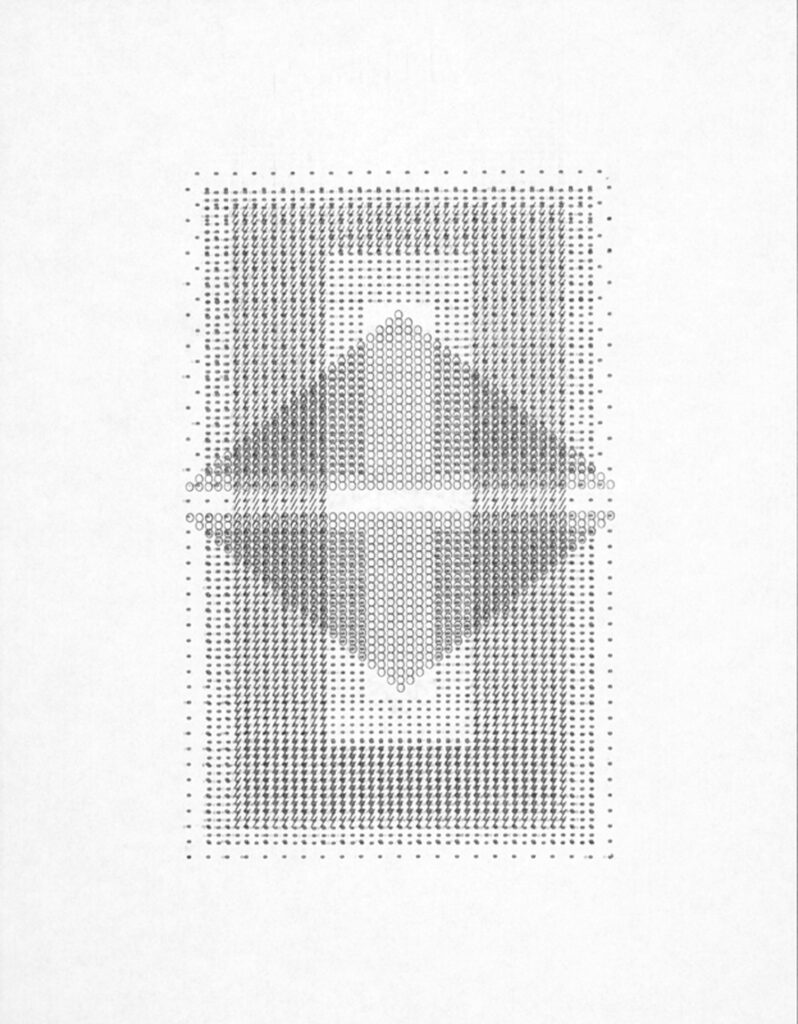

The last seems a bit more like a study of geometry, a bit more straightforward than the other two. Though that is not to say simpler. In fact, there appears to be a third kind of mark here, a slash, while in the previous two there are only two kinds of marks. The more readily accessible quality of this third drawing may come from the fact that most of the angles in this composition are right angles, while in the other two they are more often acute and obtuse. That and the appearance of the top-most layer, an equilateral diamond, is cut out in the center by a completely blank line segment, producing a more lightweight feeling to the composition opposed to the density of the others. In addition, the outermost perimeter of the composition is a border of singular dots placed at twice the distance of what is inside, which does not touch the perimeter, but stops one or two spaces short, such that there is another blank space running the length of the perimeter.

Did Harry keep these drawings more private than his other works? They feel quiet, subdued, compared to the jazz paintings and the stills from the films. It may be fair to say that these drawings represent a saner state of mind for the artist, who suffered significantly when putting into practice the more chaotic methods of his other works. As if he found an order that fit—at least for a moment. Here, the interview with Igliori at the end of Part 1 ought to be given special attention considering her relationship to Harry and her exclusive presence at Harry’s untimely passage—she recounts him crying out, “I’m dying, I’m dying, I’m dying,” between coughing up a gush of blood. She suggests as much about the order he found later in the interview: “. . . we get the awareness of the patterns that plague us and then we can release them.” When plague carries a particularly literal meaning in a place like New York where Harry survived on a diet of books and records. He said, “I thought for a while that drinking got me out of food and shelter, but it’s a way of living that is pushed underground.” (Dereliction made invisible by the rest of the city—compare to the rediscovery of the Bubonic plague in Los Angeles’s Skid Row.) Patterns for Harry were everywhere, if not everything. While the demands he placed on himself to work strictly on his own terms—refusing gallery representation, for example—centralized the public-private dynamic that characterized much of his life. The challenge of the recluse living in the city. The woman he called his wife describes him as a dwarf or troll. He was so often, according to his friends, behaving as an absolute pariah. What was going on in his conscience?

Answerable to the final facet of the book that you’re going to address, a small suggestion with a large consequence, from Harry’s remark about graven images in same interview with John Cohen. He says, “Movies are a sort of sin; it’s connected with graven images, looking at films or any type of art.” His words, implying a considerably sophisticated understanding of Moses, especially the second commandment, according to the Reformed numbering (the Romans and Lutherans blend it with the first): Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image in the likeness of anything in the heavens above, nor the earth beneath . . . nor bow down to them, nor serve them. Roughly, if memory serves. How is it applied as such in Harry’s own mind? One would think, in a snap judgment, that Harry did not actually believe his own words. Any type of art? Isn’t that more of an Islamic doctrine? Then again, early modern reformers in England took issue with the theater. One has to think carefully about these things. How did Harry come to this understanding about second commandment violations? What, I wonder, did he think about the reasoning: For I am a jealous God? God’s jealousy, unlike our own, is perfectly harmonious with his love. Harry, the genius he was, must have had something to say about these things. Aleister Crowley prowls in the background here, roaring. But Harry must have had a good reason to make this remark, considering the economy of his interviews.

Perhaps further clarified by the autobiographical notes Harry submitted to Naropa Institute’s Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, where Ginsberg secured Harry a teaching position near the end of his life. These notes appear early in the book (somewhat foreshadowing) in Harry’s own hand in an image of a page from a notebook: His reason for coming to Boulder is to find out why he’s such a damn fool, and has heard that Naropa is the best place to find out such things. I. “The rationality of namelessness” II. “Is self-reference possible?” . . .

Opening the clearing above, with the questions about the Law, opening such questions to further complications. Take the note on self-reference in light of the “Liar’s Paradox” or Russell’s—the latter more abstract but addressing the same issue. A paradox cannot be absolute, or another way to say it is a paradox is always contingent on our finitude. Harry would have understood this. In light of the paradoxes that arise from self-reference, specifically, Harry questioned and tested fundamental pieces of his aberrant “world-view” until the end. The remark about being a “damn fool” has to be taken as earnestly as Socrates. To recognize one’s own folly requires wisdom.

What if the antinomian sections of Harry are as natural and indifferent as the moon occasionally shining in the middle of the day? Much like the rationale of the Tantric itinerants of the Indus valley ca. 1300–1400. Certain philosophers do things behind your back. Buggery, according to Deleuze. It definitely happened to you. The fires. It’s really not okay to explain away the antinomians. Not aligned to truth. But it’s plausible. One checks all the angles.

D. Beveridge served in the US Navy submarine service during the Global War on Terror. His work has appeared in First Literary Review-East, Local Knowledge, and various art galleries in Los Angeles.

This post may contain affiliate links.