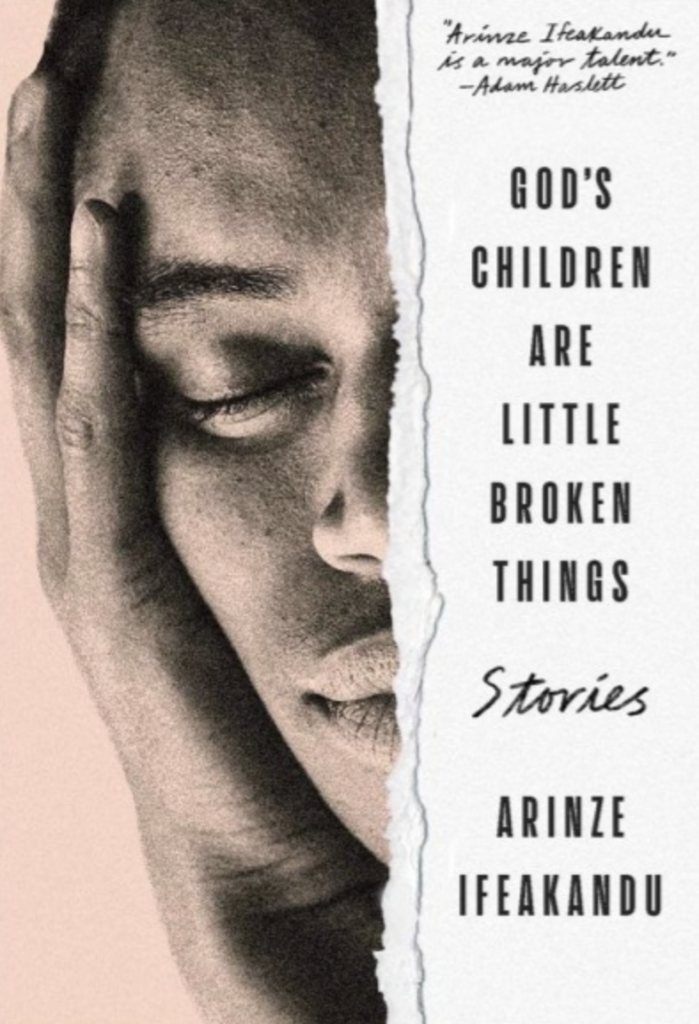

The young Nigerian men who inhabit Arinze Ifeakandu’s tender story collection God’s Children Are Little Broken Things wish deeply to be known. Their quest can be exquisite, but also arduous and often heartbreaking in a culture that denies and erases queer lives, where one must navigate the emotional vulnerabilities of youth, and families are either inaccessible, forbidding, or confused about how to love their children. Sex is one place to be deeply known, even a refuge. These stories beautifully affirm sexual joy. But sex can also become a tool of power, even a weapon. Love in these stories always feels tentative.

My conversation with Ifeakandu reconnected us after a first meeting at the 2019 Lambda LitFest when he was beginning to shape this collection. I spoke with Ifeakandu this past summer about the themes that link these young characters, how they cope with ostracism and cultural oppression, with troubled families and their inner wish to flee despite a longing for intimacy. We also explored interesting craft questions about his narrative point of view choices and how he foregrounds multiple Nigerian languages in shifting ways to draw out character and relational dynamics.

Erik Gleibermann: The collection feels like a tableau of young men searching, especially in and around the university years. How do you see these young men in conversation with each other across stories? Were you ever imagining the voice of one character connecting to or contrasting with another character when you were writing?

Arinze Ifeakandu: I wanted masked men in the collection, I wanted fem men, men who were out, men who were in the closet, men who had some kind of relationship with women, men who always have relationships with men, as multifaceted as possible—because that’s the experience I grew up with. I wanted the book to be as realistic as possible without it seeming to be some kind of political statement. It was important for me to make sure that these characters feel like friends and brothers.

When you were a finalist for the Caine Prize with the title story, you were in your early 20s. Over the course of time from when you were an undergraduate at The University of Nigeria, Nsukka through the Iowa Workshop where you finished the collection, how have you grown in your writing, and how is that reflected in the book?

I write a story and by the time I’m done writing, a year or two has passed, and then I look back at the old story and something has changed about me, even just the way I think about the conflict between two characters. And then I go back again with new experiences, new knowledge, new ways of seeing the world. Some stories felt more internal in the sense that I had to grow with them.

Time passes, you write a new story, and you solve a problem you were struggling with in a previous story. You might not fix it in that previous story, but you come to a mystery and you realize: I don’t need to spend a couple of months thinking about how to deal with this. I already know how to do it. Writing is always problem solving. There’s the fanciful and beautiful part of imagination and inspiration. But there’s also the very practical, very mathematical part: How do I structure, how do I want to tell this. Like how memory functions; that’s a structural thing. Flashbacks are wonderful, but I’m not big on flashbacks. It goes back to that sense of realism. I want the experience of the story to be as organic as possible. And the answer to that is structure.

You also think of diversifying because you don’t want to repeat. There were stories I knew I wanted to write in a higher register than others. For example, in “What the Singers Say About Love,” I wanted a straightforward voice. I wanted something to the point, not poetic, with as little complication as possible. But of course, the complications came in because these are characters in society and society is complex. But I wanted it to be less dramatic and have that reflected in the language. In “Happy is a Doing Word,” the two characters grew up in the same streets, but I wanted them to move apart. And a solution was to have the community where they grew up function as a character. The universal voice that begins the story is grounding. As the characters move apart physically, the voice also moves apart.

When intimacy is expressed in these stories, the joys and the perils are so often intertwined. These characters experience risks at every moment because of the constant threat of abuse, humiliation, and ostracism if outed, as well as potential self-shaming. Characters who face such challenges can turn toward each other and they can also turn on each other and themselves. What were you trying to do, working with this tension between the oppressive quality that your characters are living under when they’re seeking love, and the tenderness and the sensitivity and the passion that they’re bringing to their relationships?

It’s not just the homophobia. The world violates you from various adverse angles and corners. It’s something universal. A lot of the characters in the book are in their 40s, but many of the characters inhabit that 20s spot. And that’s where a lot of internal tussling happens because you’re just at the cusp, your eyes are opening and you’re also moving into a sense of responsibility.

Can you talk about how you explore sex? Sexual energy runs through just about every story and I’m struck by the richness and range of sexuality, the passion, tenderness and intimacy, but also the estrangement and aggressive exertion of power.

It goes back to everything being realistic. There are moments of loving sex, moments of almost violent sex, moments of awkward sex, sex that is not sex. There’s sex that is not really mutual, that’s selfish, where someone just wants to get off; and there is sex that is loving, where someone wants to have a connection. And there are moments of voyeurism. I’m thinking of “What the Singer Says About Love,” where the two characters are in the room and there are sounds coming in, they’re participating in a rambunctious way and laughing. The gay characters in their own room are experiencing the freedom that heterosexuals have.

How do you see your characters struggling for closeness with family, particularly the young men? There are some pretty severe family situations. Many of the families are fractured by domestic violence, marital betrayal. And then of course, there’s also homophobia.

I joke with my friends all the time about gay boys and their mothers. It’s a consistent thing, at least across the life of my friends, whether they are Nigerian or they’re American, that there is a closeness that they have with moms. Before I came out to my mother, I would play the devil’s advocate when issues of sexuality came up. She is a Christian woman, but laid back in a way. She has a disposition of letting people do their thing. She’s supportive. I remember with my auntie I asked if I would I no longer be able to come to the house and stay with my cousins if they found out I am gay.

Some of my own anxieties might have played into the representation of the characters. What does it mean for young people who are still finding themselves to move through the world holding a secret? When I was coming out, I would get into conversations with people and ask them trick questions to see their opinions and to see if I was actually safe to come out to them. Even when people said something homophobic or ignorant, there was a way they would say it that made me think maybe coming out would actually change their mind. So, I’m thinking my mother loves me, my brother loves me, my sister loves me. But I’m also thinking there is this aspect of myself that I’m not sure they would love. I wanted to show families with love where physical violence was not part of a way of correcting.

The point of view is almost always third person, though there’s a lot of diversity within third person. And there are two in second person and one in first person. How do you make your point of view choices?

With the two second person stories, it was mostly about the musicality. There’s an immediacy to it. As a reader, you’re deeply invested. It’s a more stripped down second person with “Good Intentions,” a more poetic second person. Third person gives you more freedom. And there is also an emotional distance that the third person gives. For example, in “Mother’s Love,” even though it’s tackling personal things, I couldn’t have gone with the first person because the emotional distance would be difficult to achieve. With the first person I wouldn’t be going into anything that I was personally brooding over.

You make the reader conscious of the multiple and shifting languages and language registers that include English, pidgin English, Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba, which characters switch across freely. Sometimes spoken fragments remain untranslated. How are you exploring character and relationship through your choices in working with multiple languages?

This collection is part of a conversation for me. We’re having debates within African literary spaces about the issue of audience. For example, the utilization of Igbo or Hausa, even pidgin. In the book, to make it straightforward, nothing is italicized that is non-English. I’m coming to the question of switching languages through the lens of audience. I’m thinking of a gay boy in Nigeria reading the book. If, for example, a character switches from English to pidgin. When a man is going to be violent or threatening suddenly his voice changes. I wanted as much as possible to capture these sorts of things. Sometimes they are culture specific, sometimes they’re universal. I was also thinking of someone who was not Nigerian, what they really need and how that would come across. The desired effect was authenticity.

Do you think of these as witness stories that document for readers in or outside of Nigeria, the conditions that queer Nigerians live in? There are some severe scenes. In “Good Intentions” you depict so-called conversion therapy when someone is brought to doctors or religious figures who use abusive practices to coerce a changed sexual orientation.

We need to talk about these issues. I would say the book is more of a response to conditions. That’s also my experience with reading, for example, with Buchi Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood and Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, how colonial education taught that the missionaries came and gave us the light of education. Then you read the history books in secondary school and realize, oh, my God, what these people did, and there’s a righteous anger in you. I’m not thinking I want to galvanize people or pay witness to something, but the kind of things I’ve read, whether it’s writers from apartheid South Africa or Richard Wright or Achebe, writers that actually speak to me, have a heft. I also want to write for my own pleasure, but if it doesn’t feel like it’s looking seriously at things, then it feels indulgent and I don’t want to write it.

Arinze Ifeakandu was born in Kano, Nigeria. An AKO Caine Prize for African Writing finalist and A Public Space Writing Fellow, he is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His work has appeared in A Public Space, Guernica, the Kenyon Review, One Story, Ploughshares, and Redemption Song and Other Stories: The Caine Prize for African Writing 2018. God’s Children Are Little Broken Things is his first book.

Erik Gleibermann is a San Francisco journalist, literary critic, memoirist and poet. He is a contributing editor for World Literature Today and has written for The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Guardian, Oprah Daily, Slate, The Black Scholar, The Georgia Review, The Kenyon Review, The Massachusetts Review, The New Orleans Review, Ploughshares, The Rumpus, and other literary magazines.

This post may contain affiliate links.