If there is something that defines Jewish history it is less the continuity of rituals, which have changed and evolved over time, but instead the centrality of a good story. The Torah, more than just a list of laws that govern Jewish life, is a narrative about how the world was formed, how the Jewish people came to be, and about how we (perhaps all of us) can move forever in the direction of liberation.

The story of American Jews in particular is conflicted, to say the least. We emerged from the historic narrative of Jewish suffering from antisemitism and blended into a broad Americanness, in a process that would best be characterized as fits and starts. As Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi said, today “all Jews are Jews by choice,” reminding us that Jewishness is less a mark we are forced to manage and instead a history that we navigate to gain wisdom and identity from our ancestors. Emerging from the Jewish enlightenment, and particularly in an American context, there has been a battle for what the crux of the Jewish story is, even when the story has echoes of the same antisemitic violence that encased our history for so long. Should we define modern Jewishness in relationships to the explosive moments of anti-Jewish violence, or through something bigger, more spiritual and aspirational?

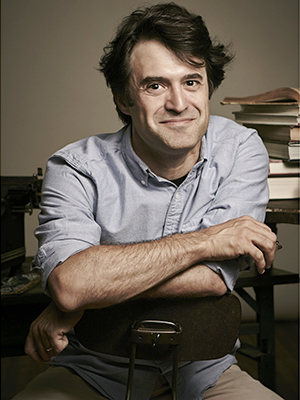

Mark Oppenheimer has spent his entire career moving through ways to tell the Jewish story. His new book Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood tells the story of the antisemitic attack at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh not by looking at the attacker or those he targeted, but the surrounding Jewish (and non-Jewish) world of the neighborhood that contained this tragedy. By looking at the interlocking lives of those in what is one of the longest running American Jewish neighborhoods, Oppenheimer reframes our most shocking moment of antisemitic violence by retelling the story as one about a vibrant, surviving, and rapidly changing Jewish community.

I talked with Mark about how his book jumps into the tradition of Jewish storytelling, what kinds of stories define Jewishness in the new century, and how to take our story back from that of violence and oppression.

Shane Burley: You chose to tell the story of what happened at Tree of Life by looking not at the perpetrator or even the victims, but about the surrounding community and the history of its neighborhood, Squirrel Hill. Why did you choose to hone in on that story, and how did you go about building that narrative?

Mark Oppenheimer:What I always tell people is that I never for a second thought it would be a fun or interesting or rewarding project to spend a year or two delving into the mind of the alleged killer. If, in fact, Robert Bowers was the killer (and the evidence is overwhelming that he was), given what we know about him it’s highly likely he spent enormous amounts of time in the most disgusting, loathsome white supremacist, antisemitic, racist, anti-immigrant and xenophobic swamps of the Internet. The Internet is not a place I enjoy spending a lot of time, even on its best days. So the idea of spending lots of time in the worst parts of the Internet to try to understand this man was never appealing to me.

That’s not to say it’s not a worthy project. I think that Dave Cullen’s book Columbine, which largely is about the two perpetrators of that shooting, is a really good book, and I think that it is really important to understand bigoted pathologies. I’ve done it a lot myself. I have written about perhaps the two leading Holocaust Deniers in the United States, Mark Weber and Bradley Smith. That was a piece I did for Tablet a number of years ago, and I visited both of them and unsurprisingly, they both have close relations or friends who are Jews, and they’re working through some stuff (in one case, an ex-wife and the other case, a sister). This is not surprising if you know anything about really sick antisemitic minds, and there’s always an interesting psychology behind them. I think it’s really important to understand why people think what they do. In fact, we need more journalism like that, and people are often scared of it.

You might remember the New York Times did a piece maybe five years ago and people were so angry that the journalists had “normalized” this person, a white nationalist, by portraying him as a well-rounded human being who, in many facets, seemed like you and me. That’s exactly what people with evil ideologies are like, and we need to see that, and we need to spend more time with them. We are currently in danger of so hermetically sealing ourselves in a little space with people who think only like ourselves that we’ve lost our zest, our interest, indeed our romance with understanding people who are radically different, even in very bad ways. So we need more people to write books on people like Robert Bowers; it just wasn’t for me. I wasn’t particularly interested, having already spent time interviewing white supremacists, white nationalists, in two cases, Holocaust deniers. I’m well aware that they are quite boring in certain ways. The ideologies they hold are not sophisticated or nuanced or intriguing or even particularly eccentric. They’re blunt, ill formed, and stupid. And so it was never a book I wanted to write.

The other book that I think some people might have written is a book about the eleven victims. That was just not a book I felt called to write. It also would have been a very difficult book to write, because in the aftermath of an attack like this the actual realities of the victims get very flattened out in the retelling. They are all portrayed heroically and as martyrs, and nobody wants to talk about their perfectly human foibles and idiosyncrasies. So that would have been a very difficult book to report, especially in the aftermath of the killing. Whereas the story of a neighborhood, and the concentric circles of interest and suffering around a death like this, was something I felt close to because my dad is from Squirrel Hill and because I knew the geography, both metaphorical and literal. Also it tied into a longstanding interest of mine, which is the way that neighborhood and urban landscape affects human interaction.

So that was the topic that interests me most and if you’re going to write a book it has to be something that will hold you for two or three years. This was the topic that was bound to hold.

There was nothing highly systematic about my process. I wanted to speak with a diverse group of people by denomination, level of observance. I wanted to speak to a cross section of people in terms of how they were related to the crime: relatives, casual acquaintances, business colleagues, people who had spotted them in the Giant Eagle supermarket and knew them to wave to. How I found people was largely through word of mouth. The last question that I end every interview with is, ‘Who else should I talk to?’ So it was really just a chain of people leading me on to other people.

You chronicle Squirrel Hill as a unique Jewish neighborhood in that it is a city neighborhood that has remained cross-denominationally Jewish up until today. How do you think the story of Squirrel Hill mirrors the story of American Jews more generally?

Well, Squirrel Hill is unusual. It’s not unique, but it is unusual in United States Jewish history. I think it’s safe to say that it’s the oldest, stable Jewish neighborhood in the country. It’s been about a third Jewish since it was populated around the time of World War I, so exactly a century of substantial minority peoplehood in this three square miles. That’s almost unheard of since most Jewish neighborhoods, indeed most ethnic neighborhoods, change dramatically. It’s rare that you’ll find a Germantown that was German or German speaking in 1920 and is still German speaking. Indeed, by the time I knew my grandparents lived in Germantown in Philadelphia, there were no German speakers left. There weren’t even ethnic Germans left.

You’ll find little traces of that, like the Little Italy of New Haven, Connecticut, which still has Italian businesses and some Italian Americans. But these things are very fleeting and ephemeral because people move on and up and out to the suburbs or other cities. Americans are very mobile in general. The Lower East Side, where my wife grew up, had hundreds of thousands of Jews in 1920, up to half a million Jews, probably more than anywhere in the world. It probably has tens of thousands now. Still significant, but a small fraction of what it once had. And that is a typical story and most neighborhoods that we think of as Jewish today, such as Newton, Massachusetts or Skokie, Illinois, were not substantially Jewish until, at the earliest, the 1930s or 1940s.

But Squirrel Hill has been Jewish since World War I, and that’s really unusual. So, what you’re able to witness in real time is how the web of connections that exist among families, many of whom are third and fourth and fifth generation Squirrel Hill families who have known each other a long time, who have used the neighborhood resources for a long time. Who sent their kids to Taylor Allderdice High School for a long time, are able to help each other in the aftermath of a really terrible event. In the transitory, suburbanized America, that’s an almost vanishingly rare occurrence.

Do you think it is still possible to have an identifiably Jewish neighborhood that maintains some of that tradition, cross denominationally? Or is this notion of a Jewish area something that has been retired in the American Jewish story?

Whenever people ask anything about the future of Jewry, usually what they’re asking is the future of Reform and Conservative Jewry. Whenever they ask a question about, say, intermarriage, birth rates, geographical dispersion, what they really mean is, ‘How are Reform, Conservative, and affiliated secular Jews going to handle this?’ Because we know exactly how Orthodox Jews are. They continue to live near each other. They continue to live near their schools. They continue to live near their kosher market and their mikvahs and they continue to marry other Jews and have children at above replacement rate. All of those things are untrue for Reform and Conservative Jews. So the question that I imagine you’re asking is, ‘Is there a future for Jewry that’s not purely Orthodox?’

That is sort of what I’m asking. Are Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews still a part of the same story? Or is there a story that they still share?

In Squirrel Hill, they are still part of the same story in part because they still live next to each other and interspersed amongst each other, and that’s very, very rare as well. That’s not something you tend to see in most American Jewish communities. Usually, the Orthodox live in neighborhoods that are substantially Orthodox, but don’t have a lot of other Jews. Often when the Orthodox presence goes up, the non-Orthodox presence shrinks dramatically, such as in Lakewood, New Jersey. So the question of whether there will continue to be neighborhoods that have Jewish amenities and therefore our natural neighbors are the Orthodox, but also attract substantial numbers of affiliated or engaged, but non-Orthodox, Jews is a really tricky question. I think it is rarer and rarer, and will cease to be a thing in most American cities that once had a Jewish population.

So whereas in 1950, or even 1970, if you were a Reform or Conservative Jew and you move to Philadelphia, you might think you would go to the Jewish Main Line, such as Penn Valley or Lower Marion, because you’ll feel comfortable there, there’s a lot of synagogues, there are kosher options, there might be a JCC. It’s hamish, there are a lot of Jews. Maybe you’re not Orthodox, you don’t keep kosher, you’re not shomer shabbos, but it’s where the Jews go so you do too. Many communities were doing this in the 1970s, 1980s, and even 1990s. These days, that has ceased to be the case. Even if you are a Conservative Jew married to a Conservative Jew and you attend a synagogue, you don’t think that you have to live in the community where the synagogue is. If you get a better piece of land fifteen miles away, even if it’s surrounded by Gentiles, you’ll make that choice. That’s an achievement that’s possible because Jews feel comfortable in America and are not worried about antisemitism around every corner.

At the same time, something is very clearly lost, and the places where you’ll continue to see a kind of thick Jewish neighborhood are largely within cities. There’s going to be a certain kind of Jewish neighborhood that exists because some portion of Jews are drawn to cities, and as long as they’re going to live within city limits they often will say they might as well live near the shul. So, for example, in New Haven, where I live, you get people who want to live in Westville because it’s near several synagogues. These are people who choose not to live in the suburbs, so that was the precondition. It’s going to be people with a commitment to urban living. I think that the idea that when you go to a suburb you’re going to pick the Jewish suburb is pretty much gone.

There are competing and numerous ways that Jewishness is presented in the book, from the Orthodox religious communities all the way to Jewish leftist activists. With such differing expressions of what it means to be Jewish, is there still a way of having a shared Jewish story? And how can we build a more diverse Jewish story that includes these multiple strands?

Obviously there are many Jewish stories. There is the Jewish story that we are all conscripted into because antisemitism isn’t going away. So anyone who continues to identify as Jewish or put themselves on the line by spending time in Jewish spaces, whether Jewish day schools, Jewish community centers, Jewish mahjong leagues, Jewish houses of worship, a mikvah, a kosher market, a Jewish retirement center, are choosing to be a part of a certain story and their fate will be intertwined in certain ways with Jews who are different than them in levels of belief, observance, politics, and other factors. That is a story that lies low usually in America with occasional eruptions of plot that conscripts us all.

That’s not a very affirmative way to construct a Jewish identity. It’s not a very impassioned way to hold a Jewish identity. It’s also not a particularly interesting one, or, I would say, a particularly appealing one. We want the storyline that holds us together because of antisemitism and hatred to go away, so it’s not a way to hold onto a positive Jewish identity. We want that antisemitism storyline to die out. I think this more affirmative Jewish identity has to be grounded around a shared participation in Jewish text and worship. Because what else could it possibly be?

For a couple of generations, there was a fairly widely shared and understood Ashkenazi American plotline that consisted of some assemblage of the immigrant experience, popular cultural representations, certain cuisine, and, by and large, Democratic Party politics (sometimes to the left or the right of that a bit). But that identity has completely fallen apart. No piece of that constitutes a meaningful Jewish identity. For most Jews under the age of fifty, it’s been a long time since bagels, Mel Brooks, Philip Roth, Seinfeld, and the Democratic Party were unifying, optimistic takes on Judaism. While I have a lot of regard for the many people who will say that their activism is their Judaism, I think there’s something, if not intentionally dishonest, then I’ll say extremely naive about that. Usually when people say that, there’s nothing meaningfully Jewish about their activism. It’s not as if they put on a yarmulke to go to the Black Lives Matter march, or hold a minyan there. They aren’t representing as Jews, and it’s not a Jewish experience for them, not really.

Most young Jews, particularly left-wing political Jews, do define their Jewishness through religion in some way. Whether it is through ritual tradition or some kind of spirituality, it does seem like the Jewish story of identity for younger Jews has some anchor to religion rather than a kind of secular Yiddishkeit.

The problem for people who think they can rebuild a highly secularized Yiddishkeit is that it actually crashes very quickly into something they abhor, which is chauvinism. One can imagine a highly secularized Yiddishkeit if you retreated to the farm or to the shtetl or the particular neighborhood of New York where several hundred other highly secularized Yiddish inflected families are, but it would have to be a fairly nomic and insular community (like a kibbutz or something).

It’s hard to imagine that working if you lived in a neighborhood with a good number of African American Christians, Muslims, secular people of East Asian descent, or any Americans who identify as spiritual but not religious. Whereas, interestingly, if the strand of your life that’s Jewish is a ritual strand, one that is rooted in ritual, tradition, or text, you can live in a very diverse neighborhood because you know that several times a week possibly you are going to be coming together exclusively with other Jews to do something that is exclusively Jewish, and that you feel obligated whether by God or conscious or the commands of your own journey to do so. I actually think if we’re going to live as full participants in this American project and maintain meaningful Jewish identities, Judaism has to be scriptural, religious, or mitzvah-based. It can’t be folkish, because we don’t live with the folk.

So does that mean rebuilding an exclusively post-ethnic Jewish identity?

I don’t think it throws out the principle of ancestry entirely. I think ancestry is a very important metaphor. It both has a lot of literal truth but also has tremendous metaphorical power because it means that Judaism is not a belief community, but rather a family. And this is a point that everyone from Adin Steinsaltz to the Lubavitcher Rebbe has made, which is that really what we are is mishpachah,family. And if you’re mishpachah, then you don’t think that somebody is outside the circle if they are a doubter, or a skeptic, or they aren’t learned, or even if they’ve married out of faith. If the metaphor is that we’re kin, then we have great obligations to each other even when we feel we have little in common or don’t like each other.

So I don’t subscribe to the idea that what we’re doing here is strictly religion. It’s not at all religion in the sense that Christianity or Islam are religions, those are faith communities. And we’re not a faith community in that way. We are a nation of kin marching through time together, and continually holding book clubs about certain sacred books. So if you believe that you aren’t necessarily jettisoning the ethnic component completely, but what you are saying is that if you want to take this family relationship and your obligations to the family seriously, then you’re not stuck in the recycling of nostalgia.

I think there is a way in which the idea of Jewish ethnicity is a largely non-Jewish concept. The idea that someone is 50% Jewish or 25% Jewish is an external idea, and in many ways an antisemitic concept meant to identify and exclude Jews, rather than one internal to Judaism. Instead, Jewish tradition sees lineages and ancestry in a way that is more in line with tribal traditions, one in which people who were not born into a Jewish family can join and then become a part of that family in a fully recognizable and equal way.

Not only is it pragmatically healthy and useful to welcome people who want to be part of the family and to have meaningful but non-prohibitive barriers to entry, but it also acknowledges that when genetic testing gets really good plenty of us are going to be revealed as “non-Jewish” according to the strictest standards. How many of us are actually matrilineal Jews? When you say that anyone who does not have a pure maternal Jewish line all the way back to Sinai is not Jewish, then how many of us would actually still be considered Jewish? We really are an “imagined community.” We are certainly living out a lot of fictions, but they are really, really truthy fictions.

The story that you tell about Squirrel Hill and the shooting is substantially different from what has been written before, and that’s its benefit. It celebrates Jewishness and Judaism rather than only mourning (not that people shouldn’t mourn as well). How do you think the story of the Tree of Life shooting is typically told, and how do you think your approach in the book is different?

I think that most mass killings are embedded in narratives that are about death, terrorism, poisonous ideologies, and security. So whenever there’s a mass killing, people want to know about how many people died, the ugly facts of the matter, the stories of who tried to get out or who saved somebody. All the dramatic stories from inside the building. Then they want to know who did it, and why they did it. They want to know if there was anything that we could have done with perfect foreknowledge to prevent it. I actually think most of those questions are really hard to answer and not even that fruitful.

I’m very skeptical of the security story, which has given rise to a very profitable industry of security consultants who tell people how to harden their perimeters. I think I’m appropriately skeptical of the kind of psychological history and psychological studies that we do about the killers looking for motivations. To me, the more interesting story is, given that we live in a world that has violence, which was true even before there were mass killings in America and even before Columbine, how that changes those of us who aren’t shot. The human condition is one that has violence and unexpected death. We should always be asking how people move through it and come together again. How they endure.

Shane Burley is a writer and filmmaker based in Portland, Oregon. He is the author of Why We Fight: Essays on Fascism, Resistance, and Surviving the Apocalypse (AK Press, 2021) and Fascism Today: What It Is and How to End it (AK Press, 2017). His work has appeared in places such as NBC News, Haaretz, The Daily Beast, The Baffler, Al Jazeera, and Jacobin.

This post may contain affiliate links.