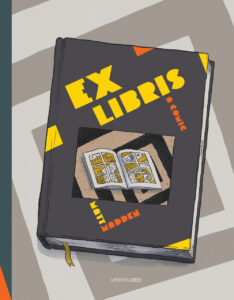

[Uncivilized Books; 2021]

It’s fair to say that Matt Madden’s Ex Libris is — in a literal sense — a very bookish book, drawing upon and integrating the resources of comics and graphic novels throughout the ages up to, and cleverly including, itself.

The book’s frame tale consists of a first-person narrator of ambiguous identity happening upon a bookshelf in the bare-bones room where they have come to recuperate after a failed relationship. The bookshelf turns out to consist entirely of comics, and they begin reading them in hopes that literature might help them find the thread of their own life. Prior to entering the room, the narrator had come close to “living in the gutter”, and since “gutter” doubles as the term for the space between panels in a comic, this offers the reader their first hint that the book is a work of metafiction. Madden is just getting warmed up; Ex Libris ends up taking the reader on a tour of many of the experimental tropes of metafiction, with winks and nods along the way to pioneers like Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, Julio Cortazar, and Gilbert Sorrentino.

Among the first allusions is one to the final line of Samuel Beckett’s novel The Unnamable — a work I take to mark the transition from the quasi-religious solemnity of the modernist period to the fundamental playfulness and irony of the postmodernist one. Beckett’s line, half-visible across two panels of an embedded comic, goes like this: “You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on.” It’s a classic example of the rhetorical device known as aporia — a sort of recursive paradox, a verbal snake that eats its own tail — and along with the labyrinthine rug on the floor of the room, it’s an apt figuration of where Ex Libris is headed.

In this first text within the text, a man attempts to escape the comic he’s in by harnessing the paratext, experimenting with reified word balloons, “plewds” (stylized sweat droplets), “briffits” (dust clouds signifying motion), and onomatopoeia (“Plop!”), even reaching across the gutter to the next panel. In another, a man loses the dimensions of breadth and time. In another, a librarian exhorts the reader (“Dear Reader”) to put down the book lest the plot suck you in as it has several characters already. These are fun gambits, if stock-in-trade for the metafictionist. Rest assured: it gets weirder.

In one doubly-embedded comic, Madden has characters appropriate philosopher Nick Bostrom’s simulation argument (in brief: either advanced civilizations go extinct before running simulations of minds like ours, or such civilizations have no interest in simulating minds, or, as per The Matrix, we’re in a simulation) to show how they are almost certainly characters in a comic; meanwhile, back in their room, the protagonist begins to worry that they too are the creation of some cosmic cartoonist. Comic by comic, the reader comes to understand that all of these embedded texts are variations on a theme: stories of people trapped or stuck. Even the books that are ostensibly worlds away from our protagonist’s experience prove to mirror their existential plight so closely it is as if the library itself were a shapeshifter attuned to, if not authored by, their state of mind. Readers of Ex Libris themselves might find the characters’ claustrophobia catching were it not that the book is so formally playful and exhilarating.

Screenwriters use the term “black moment” for that beat toward the end of a story when a character symbolically — and sometimes literally — dies before rallying into the last act. That moment comes in Ex Libris in the form of a literal black page (“The room fills with black ink”). Resurrection comes by way of a comic called La Mulata De Cordoba, about a witch who escapes from prison by drawing a ship on the wall with a piece of coal and then sailing away on it. Inspired by the witch’s example, the protagonist concocts to free themself through an act of creation: “I don’t need to play the victim. I control the story now.” It’s here where Madden’s experiments with the strange loops of metafiction are at their most rousing and original.

Formally speaking, Ex Libris is undeniably brilliant. Madden is a master visual ventriloquist, as anyone who has read his book 99 Ways To Tell A Story will know, and Ex Libris contains something like twenty different genre idioms, from Golden-Age superhero to detective noir, European to Japanese, Victorian to modern. In fact, Madden is so good at this sort of pastiche that I can’t help but wonder what it would look like if he assimilated all of these influences into a visual style unapologetically his own. To be clear, 99 Ways and Ex Libris are both great, and I’m glad they exist, but I’m also skeptical of the core postmodernist tenet that literature is exhausted and all that remains for artists is to sample and recombine the work of their forebears.

To be fair, I don’t think Madden is saying that either. Certainly pomo experimentation in the latter half of the twentieth century opened itself at times to accusations of chilly formalism and solipsism, but at its best, metafiction can become a site for interrogating and transgressing various sorts of boundaries — ontological, physical, political — and those moves can be as emotionally and culturally resonant as any in realist narrative. I hardly think it’s an accident, for instance, that, against a backdrop of fierce culture wars, Madden makes the pivotal character in his book about liberation a woman of color.

And while the moral of Ex Libris — “I’m so tired of letting outside forces determine my narrative” — may feel a touch on-the-nose, in a time when new forms of media have weaponized our penchant for groupthink, and inherited ways of life are leading us into ecological collapse, I’m not sure it has ever been more important for us to hear it. These traps have walls. Break them.

Tom Gammarino’s most recent novel is King of the Worlds. Recent shorter works have appeared in Tahoma Literary Review, Bamboo Ridge, Entropy, Hawai’i Pacific Review, and The Writer, among others. He teaches literature and creative writing at Punahou School in Honolulu. tomgammarino.com

This post may contain affiliate links.