[Studio Anugraha; 2020]

Eight years ago, after my graduation from law school, I moved to Delhi. I lived in a crummy paying guest accommodation in the north part of the city, before moving to my aunt’s place in south Delhi. I took up an unpaid position at the Delhi High Court. I did not like the work. This was not the life I had envisioned for myself. Unable to wade through these thick waters, I was mired in an existential crisis. Thinking of some second-hand advice I’d heard about not being in the profession you love, I trawled through Facebook looking to read something, anything, by way of which I could comfort myself. On one such night, with 21 mutual friends, I arrived at the profile of Mumbai-based Nitesh Mohanty.

In the first of his many public posts, he had shared something to do with perseverance and finding meaning in the car tire marks left on gravel. Eight years down, I can clearly recall that specific, oppressively lush, July afternoon. The front porch of the high court was sparsely populated, as usual. After lunch, as I stood in a strange and dappled corner, lingering in a food coma, sunlight knifed through the trees and created long patterns on my cheeks. Some spell came over me as I cycled through his entire timeline, one post after the other.

He spoke with a vehemence and passion of a believer, a lover, a seer who knew a lot about the kind of loneliness I had unknowingly been experiencing. His words, accompanying photographs, and timing: everything was ordinary, yet singular. A fleeting afternoon shadow caught by his camera in black and white. A set of words describing the dashboard of jangling curiosities one feels when they see a whisper of crows pass by. A grain of inspiration there, a thread of unique physical ties of the everyday captured in photographs there. I was mesmerized. That long afternoon — and a few other pocketsful of time like it, all of them moments of chance existential intimacy — came to occupy a pregnant space in the back of my mind as proof of something that I couldn’t put my finger on. And these thoughts returned to me almost every day during the pandemic.

Earlier on in 2020, Mohanty, a visual artist, photographer, and illustrator by profession, published his photobook nowhere, his first and only self-published book. Strongly rooted in the present time, when the world is witnessing grief at a large scale, these photographs create a space for rumination.

In the last few years, through his various social media accounts, Nitesh religiously chronicled the impact of his wife Diya’s brain tumor on both their lives. This book is a catalogue of a selection of photographs from that time. Grief and loss emerge in these as the principal emotions. It is studded with vestiges of the couple’s time together, his life as a caretaker, and the experiences of a lonely lover, who loved and lived with a partner whose health was constantly flailing. Though pulling fully from his life, the book and its photographs suddenly captured a new poignancy in that tremulous year that 2020 had been, offering help to all of its readers to navigate through this deeply mournful time.

Mohanty’s work can easily be mistaken for the popular genre of inspirational Instagram photography, but it beautifully transcends it in singular ways. His photographs focus upon exceptionally mundane moments, but in those Mohanty ends up capturing something that is beyond what is immediately perceptible to the eyes. His metaphors are precise, just like his various inspirations. The photographs are portraits of ordinary moments from the life of a caregiver, which depict with specificity the various moods and looks of a particular life and time. They manifest the dignity of his subjects, while staying immersed wholly in their milieu.

Through these photographs, Nitesh displays his uncanny ability to draw compelling images from lay objects. In his deft hands, ordinary things turn into points of ingress into the past. And this happens so often, I felt my own memory coming alive in tandem with his. Milling about his photobook on crepuscular evenings during Delhi’s lockdowns, I felt strangely seen, my misery enlightened in the light of a photograph Nitesh made of bare, tired hands of a lonely caretaker.

The oblique nature of his visual imagery is another one of the features that makes his work stand apart. There is no direct reference to medications, but a strong visual element of the long waiting hours spent by caregivers at home and in hospitals. This allows the photographs to take on a more universal appeal, despite their specificity, capturing the essence of survival amid sheer hopelessness. For example, there is a photograph of Diya standing by the beach. She gazes intently into the horizon, as Nitesh captures her reflection on the sand. A husband stealing, perhaps preserving, a mundane moment from within the couple’s very private life.

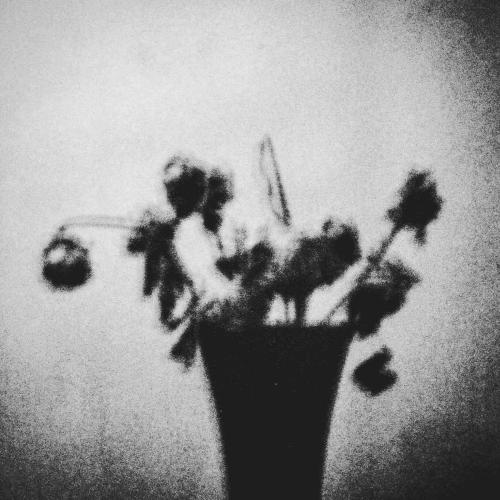

Bordering, at times on the voyeuristic, these images are acutely personal, but Nitesh knows when to hold back. There are sinuous black and white shots, glimpses into a close personal space that he tries to capture, but it is never direct for the reader. Sometimes I feel the gaze reflected back at me. In one of the photographs, I feel right at the middle of the living room of his aunt’s house in Bhubaneswar, unsure if he’s showing me how perfect isolation can be, or if it’s just a photograph of a lovely vase full of wilting flowers. Some of the photographs are heartbreakingly gorgeous, making me feel as though he has managed to crack the hard shell of totemic longing and grief. Some of his photographs have a weird dream-logic of an impossible life, while some put a finger to the exact soul warping longing and nameless loneliness that so many of us go through. Even though I’ve never been anywhere close to the various geographies he explores through his work, there is a peculiar sense of familiarity. The book, much like his Instagram feed, has for the last couple of years helped wield a yolk of deep love and authentic beauty. The photographs arranged in the form of a prayer animate the spirit through the dark and the lonely.

In misguided hands, the subject matter could be treated opportunistically, fodder for easy emotional impact. But in Nitesh’s, the photographs take greater import. They grant visibility to subjects, emotions, and experiences that have largely remained absent from a cultural point of view and have gained renewed obsession and prominence in the post-pandemic context. The somber, emotional landscapes of these photographs draw out the more universal territories of the economic and social pull and tug of the weathered and wrinkly lives of those who give care.

A dark palette and an unromantic gaze that is unflinching in its analysis creates a tension that lends itself poetically to the COVID-19 pandemic. The tones in his photographs shift from the iridescence of the exhaustive work of caretaking to the near-grey, astronomical backdrop of the sea in the dark of the night. Some images reminded me of Andrei Tarkovsky’s work, looking more like abstract pastels than photographs. They capture a feeling more precisely than any set of words will ever be able to, and in that they afford a novel language to mourning.

It was Tarkovsky who said, “A poet is someone who can use a single image to send a universal message,” and Nitesh’s work holds these words as the ultimate truth. In trying to capture moments from his life, he reveals an identity fashioned out of longing and revisits some of the most poignant moments from the last decade: his singularly lonely time as Diya’s caretaker, the trauma from losing his beloved to the treachery of a disease, pockets of joy found in otherwise overlooked places, unearthing lust and love, understanding his own self, creating solidarity among an unknown tribe of readers, and ultimately, suffering a great loss. He affords a distinct character to each photograph — a human, a place, an idea — its own agency. There is a sense that he wants to embellish certain details, to push the story forward and make it more universal. In doing so, he invokes an autobiographical reading, while founding on truth, realizing it by the imagination and keeping it honest in a way that it becomes universal.

In a certain way, Nitesh’s photographs are also therapeutic, a kind of an antidote to the prescient topic of death. In the present jumbled times, he makes it look a bit universal, unnerving but also very real — dealing with the loss of a loved one. Life through his work looks like an act in stumbling together and finding a beauty in that, in collaborating very closely with one’s own life and keeping it that way. And it rings true. A lot of times through these photographs, I caught myself sensing what Nitesh might have been feeling.

Before the pandemic, there was a sense of invisibility to the experience of losing a loved one to a deadly disease. Millions died every day still, but those of us not directly connected went on with our lives, never noticing, rendering the pain and suffering of others often unseen. An important work that nowhere also does is that through it, Nitesh somehow retroactively renders our collective grieving experience less painful. Just by virtue of putting this set of images together, Nitesh makes us feel that we have all inhabited this same temporal space together.

In the current times, when humans are unable to completely grasp at the insurmountable losses, heaping atop each other, this book is a beautiful way to hold someone so dear this close and lovingly in one’s memory. In a way, Nitesh works this same magic through the visual imagery of his work and builds a world that draws from his own life and, in turn, makes the reader’s experience more real, more beautiful, and more our own.

Anandi Mishra is a Delhi-based writer and communicator who has worked as a reporter for The Times of India and The Hindu. Her writing has been published by or is forthcoming in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Virginia Quarterly Review, Brooklyn Rail, Al Jazeera, Chicago Review of Books, Aeon, Popula, The Atlantic, Harvard Review and elsewhere. She tweets at @anandi010.

This post may contain affiliate links.