Harriet Scott Chessman is the author of five novels, including three historical ones—The Lost Sketchbook of Edgar Degas, about a cousin of Degas in 1880s New Orleans, The Beauty of Ordinary Things, set in and around a Benedictine Abbey in rural New Hampshire in the 1970s, and Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper, 1880s Paris seen through the eyes of Mary Cassatt’s model and sister Lydia—as well as two contemporary novels, Someone Not Really Her Mother and Ohio Angels.

In writing my recently published historical novel, The Book of Lost Light, about a photographer’s family in the San Francisco Bay Area before, during, and after the 1906 earthquake, I found Harriet’s writing about the intersections and mysteries of art, memory, and time to be immensely helpful and inspiring. Harriet and I had met when we were members of a small book club with other fiction writers, and we’d become friends as I was writing my first historical work of fiction, having previously only written stories set in contemporary times. I was delighted to speak with her recently about the ways historical research can fuel creativity, the process of identifying the central characters, and the helpfulness of poring over old maps.

Ron Nyren: How does research inspire your fiction—do you do a lot of it up front, or do you research as you write?

Harriet Scott Chessman: I do both. With Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper and The Lost Sketchbook of Edgar Degas, it was the art that I fell in love with first. I was lucky to have access to brilliant scholarship about Cassatt, especially Nancy Mowll Mathews’ Mary Cassatt: A Life, and Cassatt and Her Circle: Selected Letters. And there’s a wonderful catalogue, Degas and New Orleans: A French Impressionist in America. As I was trying to figure out my subject, and then all during the writing, I looked at all kinds of stuff: maps, newspapers, letters, journals, fiction, historical accounts—whatever helped me imagine these characters’ worlds. But I’d also say that, for both of these novels about art, my primary resource was always the paintings themselves. I would pore over them, with my characters in mind, trying to understand how, in a sense, the paintings themselves were telling stories. What was the starting point for The Book of Lost Light?

The only thing I had to begin with was a “What if?”—what if a boy grew up being photographed every day of his life as part of a project to capture the passage of time? I thought it would be set in contemporary times, but I didn’t know what the purpose of the project might be. For a long time, I was hunting for the story. Then I thought of Eadweard Muybridge, the man who pioneered the photography of motion in the 1870s. I started by reading everything I could about him, and I thought, what if my photographer were a former protégé of Muybridge? I gave various drafts of the early chapters to my novelist spouse, Sarah Stone, and to the rest of my writers’ group. More characters fell by the wayside until I settled on my central trio—Arthur, the photographer; Joseph, his son who tells the story; and Karelia, Joseph’s older cousin. And then early on I knew I wanted to include the 1906 earthquake and fire in this story of a man who’s trying to create an enduring record of time. How did Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper evolve over time?

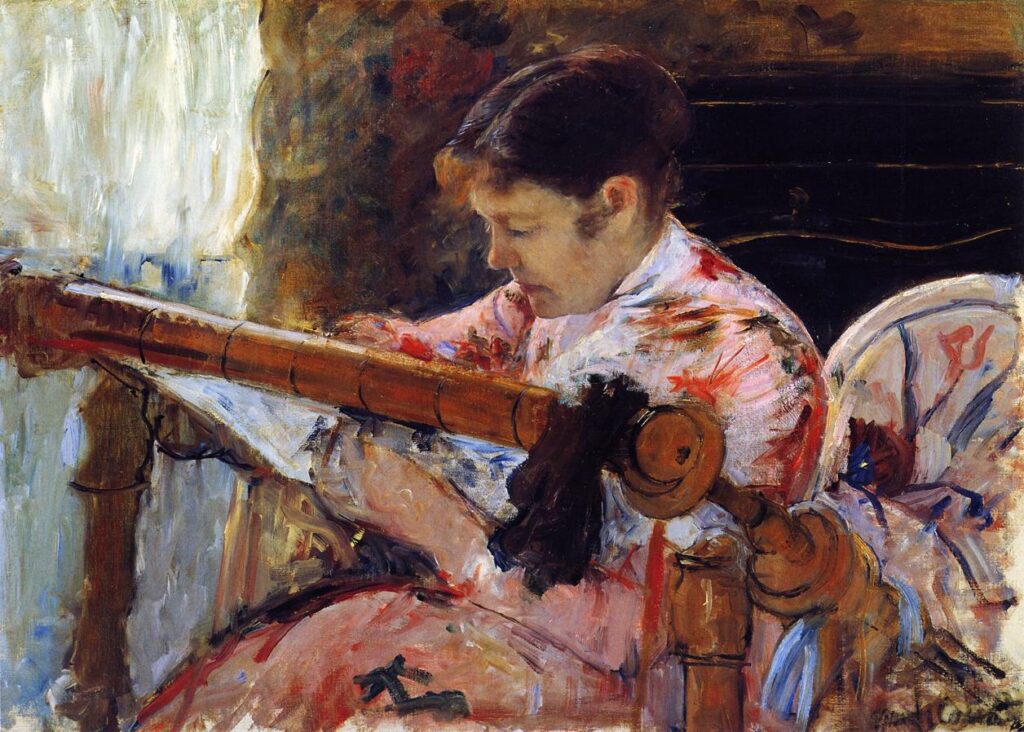

Originally I couldn’t figure out my points of view; I tried at least seven! Once I realized that the relationship between Mary and her sister Lydia would be central, I thought the first half would be in Lydia’s voice, and the second half in Mary’s voice, after Lydia’s death. I hoped to chart Mary’s recovery from the grief of losing this beloved sister and muse. But I came to a certain moment in the writing of the Lydia Cassatt half, and I felt, no, this is where the whole novel has to end, in this moment when Lydia is contemplating her own death, but she’s still very much alive. It’s a floating, lyrical moment that unfolds out of Cassatt’s gorgeous final painting of Lydia, done in 1882, Lydia at a Tapestry Frame. Sometimes I still wish I could have found Mary’s voice, but I just couldn’t.

It’s funny how you can know a person so well and yet not be able to inhabit them. And then you could with Lydia.

Yes! I’m drawn to characters who are more on the margin. I’m fascinated by a courageous genius like Mary Cassatt. But I’m more drawn to a figure like her sister—I could barely find her sister in the materials that were available. So it gave me this whole open field. Same thing with Edgar Degas for The Lost Sketchbook of Edgar Degas. I wrote many drafts of the novel in Degas’s point of view, first person, third person. He just could not come alive on the page. It wasn’t until I discovered his cousin, Estelle, that I knew I had the voice and character I needed. I fell in love with her, as I imagined her, for her courage and her presence. She became blind in her late twenties, yet married Edgar’s youngest brother Rene, and had many children, and in the midst of all that she became a model for her cousin Edgar. How did the character of Karelia come out of your research? Did you know early on that there would be a figure like her coming into the home of Arthur and Joseph?

In the early drafts, I was asking myself, is Joseph’s mother alive, or who else might be part of this family? As I was reading about other photographers in California in the early 1900s, I found out about the pictorialists. I was fascinated by the women pictorialists, particularly Anne Brigman.

Ah, so Anne Brigman was real!

Reading about those women gave me a sense of the challenges women artists faced at the time. Brigman grew up on the island of Oahu in Hawaii, and when she was a child, she hated having to sit still on her family’s haircloth sofa for long morning prayers—she was dying to run around in the great outdoors. As an adult in California, she would take long camping trips and hike through the Sierras with her camera. Although Brigman doesn’t appear directly in the novel, she’s a role model for Karelia, and her yearning for freedom in nature inspired my sense of who Karelia was.

It’s beautiful to watch Karelia grow into a photographer with her own vision. When we first meet her as a 12-year-old, we don’t know that she’ll come to craft something of her own. I love that she finds a community of artists. Your novel made me think a lot about how art gets created.

With historical writing, there is always that question, how much do you include a “travelogue” element so the reader has that “I am there” feeling in the exotic landscape of the past. Because if you read authors of the time like Willa Cather, she was addressing readers who knew the time she was writing about, so she didn’t have to conjure anything specific to the time period because she’s just in it. She describes landscape beautifully, of course, but without a certain kind of showiness.

I love that. Yes, it’s so hard to avoid the impulse to dazzle, like “Look at this! Aren’t you amazed by my historical knowledge?” Ahhh! So when I am trying to write about somebody who lived a long time ago, I try hard to sink in and inhabit this person as fully and naturally as possible. Often I choose the present tense, because it helps me stay in the moment. If you hold fully to the world your character is in, and you don’t try to teach, you’ll be O.K.. This 1st person, present tense approach helped me inhabit my character Sister Clare too, in The Beauty of Ordinary Things. I guess I’d say, my first impulse isn’t to make history come alive. My first impulse is to find my characters and inhabit them, and out of that to write a good story.

That relates to what you were talking about, not inhabiting Mary Cassatt, but someone like her sister, someone on the margins, who we would have more questions about.

Yes. I have written about other, utterly fictional and more contemporary characters. But there’s something so intriguing about finding someone who actually lived and wondering, what was their experience like, what didn’t get written down? What was on their mind, what was difficult about their lives? You bring us so richly into the inner and outer world of your characters, Ron. How did the history you discovered help you bring your characters to light?

In researching my novel, I read a lot of accounts of earthquake refugees, and so many of them were living in tents in San Francisco, and then I came across the mention of all the refugees who fled to Berkeley and the Berkeley residents who took them in. So many Berkeley residents took in refugees, whether they knew them or not, and put them up in basements and backyards and attics. That piqued my imagination more than the thought of them living in San Francisco, which was more well documented. Then a nonfiction book came out, Earthquake Exodus, 1906: Berkeley Responds to the San Francisco Refugees, and that helped immensely.

It’s wonderful how you imagine that migration from the city to the country—because you help me see that Berkeley was more rural at that time. It’s fascinating, the idea of a large population going across on a ferry to another land. And you make Berkeley seem so real and also magical. I mean, Berkeley is magical already! How much research came out of your life in the Bay Area? Because so much research is actually personal, and I think this is important to get at.

In 1991, a few weeks after I moved from Connecticut to Albany, California, I stepped outside my apartment one morning and saw smoke rising from the Oakland Hills less than five miles away. I’d arrived here worried about earthquakes—the 1989 Loma Prieta quake was still fresh in people’s minds—but I hadn’t even considered fire as a possibility. I was plenty far enough away to be safe, of course, but it was heartbreaking to hear about the loss of life and homes. I spent a lot of time, especially in my first year, walking the Berkeley hills and studying the way the roads and houses wound through the trees and the topography, and when I moved across the bay to San Francisco, I walked as much as I could, soaking up the city. In Connecticut, you can get hurricanes and blizzards, but they feel like visitations, and they announce themselves before they arrive, whereas in California, the potential for fires and earthquakes to start swiftly and without warning lends a different feeling of vulnerability. Are you always writing about places in history that you have personal familiarity with, or do you rely only on research sometimes?

I lived in Paris for a year, when I was in my early twenties, so I had a sense of that city. I could imagine the Cassatt family living there. And I knew all the places and some of the culture I wrote about in The Beauty of Ordinary Things: Irish Catholic families in Boston suburbs, southern New Hampshire, Yale. I’m very close to an Abbey in Connecticut. I’ve only visited New Orleans once, but New Orleans in the 19th century was really different from the present day city anyway. And I loved studying maps and newspaper articles of the time. Also, I read Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, which gave me a sense of the texture of life in Louisiana, in the late nineteenth century.

Yes, I also found it helpful to read novels of the early 1900s set in the San Francisco Bay Area, like Jack London’s Martin Eden, Gertrude Atherton’s The Sisters-in-Law (which begins with the earthquake), and Frank Norris’s Blix and McTeague. Blix isn’t as famous as Norris’s other novels, but it gave me a sense of how a courtship might unfold in San Francisco around the end of the 19th century, and how young men and women were pushing against the conventions and expectations of the time in terms of relationships.

Yes, fiction is so helpful. Also, memoirs! For my novel The Beauty of Ordinary Things, I was grateful for Tim O’Brien’s moving book The Things They Carried. And I looked at photographs of soldiers, and read some compelling 1st person accounts of the Vietnam War.

What more contemporary writers have influenced your work or provided inspiration?

Oh, I have loved so many contemporary writers! Kazuo Ishiguro is one of my all time favorite writers, because of his immense subtlety, and his way of telling a story obliquely, so that, as you realize what the story really is, you find yourself implicated and drawn in very profoundly. A Pale View of Hills and The Remains of the Day are two of the novels that inspired me to start writing fiction. Virginia Woolf has always been the sun and moon to me, for her amazing experimentation and sense of voice, and her trust in the internal story. Toni Morrison, starting with The Bluest Eye, has been a model to me for how to tell the hardest stories with courage and unblinking ferocity. Alice McDermott, Colm Tóibín, Edna O’Brien, Jhumpa Lahiri, Michael Ondaatje, all of these writers show me something extraordinary about how stories can be shaped with vision and beauty, out of the chaos and sorrows of history. What about you, Ron? What contemporary writers do you look to for inspiration?

Penelope Fitzgerald has been a big inspiration for me. I love her work beyond all words, especially her historical novels The Blue Flower and Gate of Angels. Helen Oyeyemi is amazing in the way she has her characters telling each other stories as part of the plot, and the inventive way she weaves in elements of fairy tales. And I love Yoko Ogawa’s stories and novels, which range from the realistic to the quite strange. What projects are you working on now, and are they historical or contemporary?

I’m working on a couple of opera librettos—one of them is a retelling of The Tempest, with Sycorax as the central character. And I’m feeling my way toward some new fiction. It may have a character who, even on his death bed, is haunted by the confusion and terror of his D-Day landing on a Normandy beach. Characters usually come to me first, and I seem to gravitate toward subjects involving memory, trauma, and healing. What about you, Ron? I’d love to know what you’re imagining these days.

I’m working on a novel based on a Greek myth. I’ve loved myths ever since I was a kid, and that shows up in The Book of Lost Light when my characters start creating and performing plays based on Finnish folklore and myths to keep their spirits up while living in tents. But with the next book, I want to set it in Ancient Greece to consider the events that might have given rise to the myths. I have a little trepidation about trying to inhabit the Bronze Age. The farther back in time you go, the greater a mystery the lives of people seem, and yet something about those old stories still catches our hearts.

Harriet Scott Chessman is the author of five novels: The Beauty of Ordinary Things, The Lost Sketchbook of Edgar Degas, Someone Not Really Her Mother, Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper, and Ohio Angels. Her fiction has been translated into seven languages, and featured in The New York Times, The San Francisco Chronicle, NPR’s All Things Considered, Good Morning America, andThe Christian Science Monitor.She also created the libretto for MY LAI, a mono-opera composed by Jonathan Berger and commissioned by Kronos. She has taught literature and creative writing at Yale University, Stanford Continuing Studies, and Bread Loaf School of English.

Ron Nyren’s novel The Book of Lost Light won Black Lawrence Press’s 2019 Big Moose Prize and was published in November 2020. His fiction has appeared in The Paris Review, The Missouri Review, The North American Review, Glimmer Train Stories, Mississippi Review, and 100 Word Story and has been shortlisted for the O. Henry Awards and the Pushcart Prize. He is the coauthor, with his spouse and writing partner Sarah Stone, of Deepening Fiction: A Practical Guide for Intermediate and Advanced Writers. Ron earned his MFA in creative writing from the University of Michigan. A former Stegner Fellow, he is an instructor in fiction writing for Stanford Continuing Studies.

This post may contain affiliate links.