[Infinity Land Press; 2020]

I have the impression that, since the time of the historical avant-garde, never have so many works entangling writing and the visual arts been so relevant. In the last few years, we’ve seen some carefully edited examples of collaboration between visual artists and writers that go beyond traditional definitions, genres, and styles, such as “visual poetry,” “conceptualism,” or “artist books.” Publishers like Inside the Castle or Visual Editions, and a significant number of experimental writers, such as Mike Corrao, Jake Reber, Mike Kitchell, or Elytron Frass, to name just a few, have adopted image design and processing as constitutive features of their literary texts.

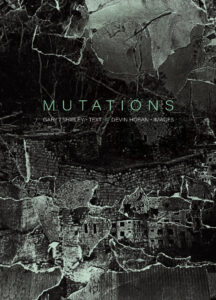

Mutations, including texts by Gary Shipley and images by Devin Horan, is a perfect example of this ongoing process of “reimagining of the imaginary,” as Steve Finbow states in the introduction, or “expanding the field” — an expression that has become the war cry of the latest literary experimenters, in this case through a fascinating poetic dialogue between greyscale photo collages and texts. The text is presented in the form of eight short stories — a genre of which Shipley is probably one of the most interesting contemporary practitioners. Horan’s collages look like they have been produced by the underground technique of gluing together some shredded pieces of printed paper. He superimposes the erotic allure of decaying flesh onto abstract inorganic puzzles, forming surreal landscapes that mimic surfaces of veined and cracked marble.

Opening this recombinant mirror-game, the first and longer story from which the book borrows its title, includes forty-eight selected quotations about mutations by well-known theorists and fiction writers. “Mutations,” which might be considered an introductory collage-text, is a story about cancer, a narration of the subtle transformations initiated by the oncogenic noise of a few rebel cells, metastatically developing into a futile resistance against the growing evidence of total body horror — a disintegrating body that will finally collapse into a semiopathically cruel work of art. We, the mutants, are also semiopaths, the ones who involuntarily make ourselves body-texts of aberrant signs — or, as defined by Steven Craig Hickman, “voyeurs of signs rather than creators, semioticians of the death-drive rather than desiring machines, cyberzombies of the edge worlds frozen on the cyberscreens of an endless night of civilization.” An endless night of survival is represented as a form of art:

My speciality is how long it’s taking me to die. I’m so many suicides by proxy I could wake up dead at any moment. (“The Transfigurations 2”)

“Mutations,” writes Finbow, “is not striving for another being, but for another mode of being.” As in most of his books, Shipley’s post-Ballardian beings are expanded and ever changing — “the only way I could stay alive was as a variable, that which could be anything and so is never something.” Bodies are inscribed into reality through the most extravagant and exquisite literary images, moved by the forces of an uncanny syntax emerging spontaneously from unlikely arrangements of all-too-material objects. Shipley’s body horror goes well beyond what we usually consider “the body” because his bodies have no clear boundaries. They’re intermingled with a senseless world and melting into it, they have too many organs in search of functions and may adopt any foreign object as an organ:

I go home every morning and eat my head out with a spoon. I’m looking to throat-cut myself per capita. This much blackness in your skull used to mean something. Brains would turn to slime so God could turn them into something else. (“Aftermath”)

For Shipley, it’s not a matter of opening our eyes, but of realizing that our body is made of many holes. There’s no real distinction between self and non-self, to the point that any relationship, no matter how theoretically aberrant it might sound, is not just possible but beautiful — one never graspable, but a temporary swirl in a flowing reality:

This is how the sigh ends. Without ending. If this thing-in-itself-thing wants something it’s already mine. My death that happens to no one just as no one happened to me. And when it comes I’ll make smell of it. Unknowing is the grace of my absence. (“Artie Schops”)

Shipley’s abject organicism engulfs the inorganic as much as Horan’s plates do, re-framing matter in a speculative nature that, as dreamed by Quentin Meillassoux, would be “capable of marginal caprices and epochal modifications, and with it a disconnection between the conditions of the possibility of science and those of consciousness.” The closing text, “Notes for a future poetics of impossibilia: Atrocity, deformity, horror and depression,” is a rare jewel in itself: a short, yet intense and splendid collection of aphoristic philosophico-poetical recommendations — in the tradition of Nietzsche, Cioran and Blanchot. Any reader would love to be left with this collection before diving into the ocean of Horan’s images: “Get poisoned, emerge poisonous. Dig a maze in the earth not a grave.”

Everything in Shipley’s writing is enigmatic and ambiguous: life is death, you’re expected to “multiply your tumors,” and Joan of Arc is a martyr and a witch and a warrior and a glamorous French woman. Like when closely inspecting small details in a Bosch painting, we can’t tell if we’re in paradise or hell.

Because she’s sharpening her nails on the flat stones of graves. Because she’s caking her face in consecrated mud. She’s bloodletting poisoned toads, and binding missals with their backs. She’s advancing on Rouen in Guerlain nails and glitter mesh Louboutin spikes. (“The Passion of Joan of Arc 2”)

Every sentence Shipley writes is blessed and cursed to living its own life while, simultaneously, becoming part of a narrative slime-colony. “Make indeterminacy your solid ground,” he advises. After all, this seems to be the way the universe works.

Germán Sierra is a writer and neuroscientist living in Spain. He has authored six books of fiction in Spanish, and one in English entitled The Artifact, published in 2018 by Inside the Castle.

This post may contain affiliate links.