This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

H.D.’s rented flat at 44 Mecklenburgh Square, a new boarding house in interwar Bloomsbury, London, was in reality one large room, with a Spanish screen delimiting the kitchen from the living area. The flat had “apricot-colored walls and a blue carpet” – which did little to rescue the room of its general staleness – and French windows “swathed in night-blue curtains.” A statue of the Buddha, ashtrays and a teapot were scattered around the space, objects of daily life and decoration.

When H.D. and her then-husband Richard Aldington moved from Hampstead to their new home in Bloomsbury, H.D. was at the time mining Greek epic and tragedy, finding ways to draw out their female voices in new ways. Her translation of verses from Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis was published in the Egoist just months before. Yet, only three months after moving their personal items in with them in February 1916, the Military Services Act conscripted all married men; Aldington was conscripted as an infantry private and sent to military training camp in Dorset. The night-blue curtains, at times evoking a sense of protection and interiority amid the ongoing, public trauma of World War I, just as quickly symbolized claustrophobia and abandonment.

Two years after H.D. moved out, Dorothy Sayers moved to London, gravitating to the possibilities of building a literary career in the city after finishing her studies at Somerville College, Oxford, and a brief secretarial stint in Normandy at a school for boys. She wrote to her parents in December 1920, “the die is cast and I am departing on Thursday to 44 Mecklenburgh Square WC1, where I think I shall be much happier.” She described her new home as “a lovely Georgian room, with three great windows – alas! Would that I could afford curtains on them!” Sayers had moved into to the same flat as H.D.; the night-blue curtains, in the interval, had been taken down.

Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars, Francesca Wade’s collective biography of five modernist women, reveals not only the interiors of their Bloomsbury flats, but the importance of a room of one’s own for their self-fashioning as public intellectuals. Their claim to a living arrangement in direct contrast to the airless environment of the Victorian family home both signified and permitted their independence.

The women at the center of Wade’s study are H.D., Sayers, Jane Ellen Harrison, Eileen Power, and Virginia Woolf – all of whom were born between 1882 and 1893, with the exception of Harrison, who was born in 1850. Each woman contributed to the modernist project, albeit through different intellectual forms, and all had the privileges that made their person and professional lives possible: race, a middle-class upbringing, and an unprecedented access to education. And each – at different points of their lives and for varying durations – took up residence at Mecklenburgh Square in Bloomsbury.

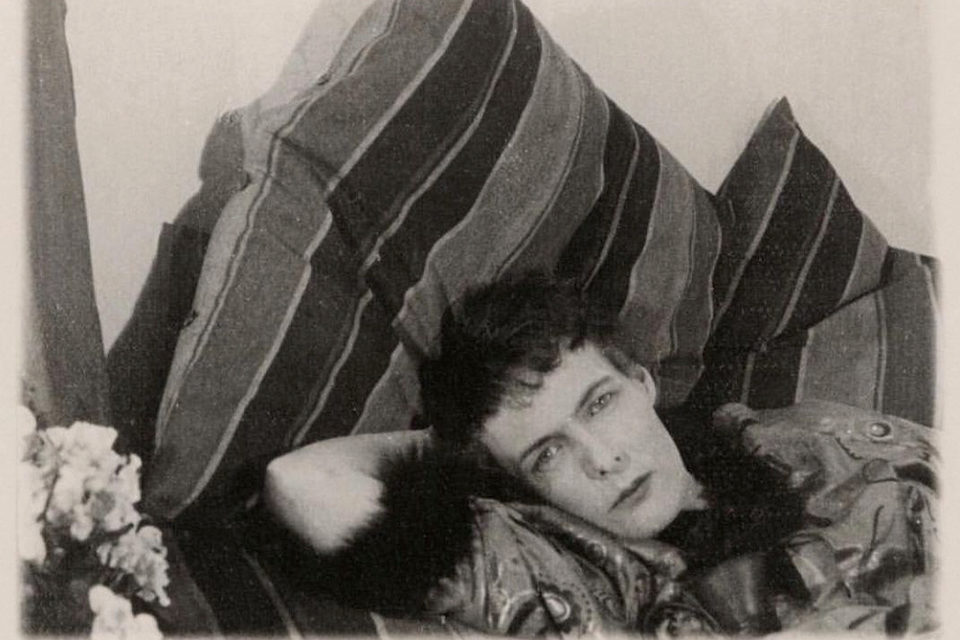

Power, having joined the London School of Economics on a fellowship intended to build a body of work focusing on women’s history, went on to pioneer the field of economic history, braiding together social science and the historical development of economies through her study of medieval cloth industries. H.D. was a writer and a poet, considered “a genius and promptly forgotten about,” Wade writes, “until she was rediscovered amid the second-wave-feminist project to reclaim lost ‘mothers,’” and was lauded for her reinvention of classic Greek tragedy and epic through modernist verse. At Newman College, a women’s college at Cambridge, Harrison applied archeology to the study of ancient Greek worship, producing major works that excavated the existence of “mother cults” in ancient culture and in so doing gained recognition as one of the first women to be considered a professional scholar. Sayers was a “doyenne of detective fiction,” authoring tales of murder and mystery that met great commercial success; she gave life to characters such as the detective Lord Peter Wimsey, who became a late-Victorian household name on par with Sherlock Holmes. Woolf, perhaps the most well-known of the modernists, brought interiority and non-linear narrative to the novel.

Yet, prior to these accomplished reputations, these modernists had some traveling to do.

H.D. undertook an oceanic leap to Bloomsbury. Born as the only girl among five brothers in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, into a Moravian Brethren community – a Protestant order known for its mysticism and esoteric rituals – she travelled to Paris in 1911 in search of new horizon before settling in London. She “at last had found somewhere she belonged” (she only returned to the United States thereafter for short visits, never to live). Woolf’s journey required less miles, but was no less abrupt. At the age of twenty-two, she departed from her family home at 22 Hyde Park Gate in Kensington and moved to Gordon Square in Bloomsbury with her siblings. Sayers and Harrison moved to London after leaving the world of academia: Sayers as a student at Somerville College at Oxford, Harrison as a scholar at Cambridge. Power received the offer of a lectureship at the London School of Economics while she was in Madras on the Albert Kahn Travelling Fellowship and while on, as Wade notes, “a boat passing between Rangoon and Shanghai,” she accepted, deciding her future lay in London.

This mobility was hardly unique to them. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Victorian household with the “angel in the house” – as Woolf described the archetypal Victorian woman, the embodiment of respectability – at its mantle began to be questioned. Alongside changing social and cultural mores, the invention of new technologies such as the telephone and typewriter opened up a number of new employment opportunities for women, leading them from the thresholds of their family homes to the doorsteps of new accommodations. From the second half of the nineteenth century to the first decade of the twentieth, the number of women employed in clerical positions in London mushroomed from a couple hundred to over half a million, according to Terri Mullholland in British Boarding Houses in Interwar Women’s Literature.

The boarding and lodging house emerged to meet the housing demands of this mobile population in the first decades of the twentieth century. Historically, men had been the archetypical lodger, but this changed alongside the rise of women, increasingly single, seeking spatial arrangements to accommodate their transient lifestyle. The search for new forms of accommodation to match their new, urban ways of living entailed a departure from their families, and soporific expectations of domesticity and respectability. The destination, the boarding house, blurred public and private – instead of keeping a border between the two in order to safeguard the latter.

Typically managed by a live-in landlady, the boarding house brought a dozen or so people together, all of whom were thrust into makeshift intimacy through shared kitchens, bathrooms and walls that did little to obscure the sounds of daily life. Often, the landlady served dinner in the evening, a guaranteed daily meal that brought renters yet again into communal space. As Mullholland describes, “the single room in a boarding or lodging house provided an alternative to the traditional location of domestic space,” in contrast to the family home, it was a “site of anti-domestic values.” The privacy afforded through a room of one’s own was counter-balanced by various forms of exposure, complicating the domestic sphere as a sacrosanct and eminently private space.

The flats in which the five modernist women chose to live, in upturning the domestic sphere and its connection to feminine respectability, offered a new material landscape fit for novel forms of living.

In a Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf states that imaginative work

is not dropped like a pebble upon the ground, as science may be; fiction is like a spider’s web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners … But when the web is pulled askew, hooked up at the edge, torn in the middle, one remembers that these webs are not spun in mid-air by incorporeal creatures, but are the work of suffering human beings, and are attached to grossly material things, like health and money and the houses we live in.

In other words, cultural production depends on the right material circumstances, which in Woolf’s perspective entails £500 per year and a room of one’s own. She knew the importance of personal financial security in pursuing a livelihood as a writer. Woolf inherited money from her late aunt, after she died unexpectedly in Bombay – £500 per year, indefinitely (“Of the two – the vote[1] and the money – the money … seemed infinitely the more important,” Woolf wrote).

The inverse to the correct “material things” implied in Woolf’s writing was the middle-class Victorian home. In this space, the drawing room was designated as the domain of the woman of the house, but in contrast to the masculinized study, it was also a living room, “a room in which you [cannot] possibly settle down to think, because anyone may come in at any moment,” Harrison wrote. This arrangement failed to provide a space for women to reflect, learn, and develop; it stifled the intellectual pursuits of women.

Against this typology of the home, Wade’s subjects sought a space that would give room to creative flourishing. The modernist women of Square Haunting all gave great thought to the home they moved into; the “way they each chose to set up home in the square was a bold declaration of who they were, and of the life they wanted to lead,” Wade writes; “a renovation of traditional living arrangements … was not only an outward sign of women’s evolving freedom, but actually a prerequisite for it.”

The materiality of the flats that these five women took up residence reflected this “bold declaration.” The ways that H.D., Sayers, Power, Harrison and Woolf used the space of their rented accommodation, and the objects with which they lined counters and windowsills reflected the interior lives that were so crucial to the production of their public selves. In a Room of One’s Own, Woolf writes that if one is to claim a room of her own, this room “has to be furnished; it has to be decorated.” She then asks, “how are you going to furnish it? How are you going to decorate it?”

When Power stayed with her great-aunt in Manchester in 1910, before her move to London, she wrote to her friend about the “cabbage wallpapers and horsehair sofas” which, to her, represented the “concentrated essence of mid-Victorianism, after the Victorians had ceased to be interesting.” She continued, exaggerating, “If I lived here for more than a fortnight I should die.” When she moved to 20 Mecklenburgh Square, she built a private domain different from her great-aunt: her desk by the window, rooms with fresh flowers and knickknacks from her international travels. “I never realized before how one’s material surrounding could affect one’s spirits,” she wrote.

The reconfiguration of inhabited space in the interwar Bloomsbury reflected, too, attitudes towards family and friendship.

As much as these modernist women desired and exercised independence, they did not seek perpetual solitude. Urban delight was best shared. The popular conception of the Bloomsbury Group – who, as Dorothy Parker said, “lived in squares, painted in circles, and loved in triangles” – hints at the colorful social world of the area’s inhabitants.

The rented flat allowed such sociality. In Power’s flat, she used her kitchen as the space for a dancing party, and “over dinners as Mecklenburgh Square, [Woolf] and her guests darted easily between contemporary gossip” such as the death of Sigmund Freud, the scandalous affair of her niece, or whether the barbarism of war will bring an end to culture. Their homes, having shifted from a site of pure domesticity, welcomed dance, drink, and intellectual exchange.

Yet, the subjects of Square Haunting sought out and depended on others in more structural and enduring ways, beyond the bonhomie. Often, the freedom to pursue intellectual work, be it Power’s study of medieval nunneries or Woolf’s biography of her friend, the painter and critic Roger Fry, relied on their finances to purchase the reproductive work of other women through the employment of maids. Power described her maid, Jessie, at 20 Mecklenburgh Square as “an admired and much-loved woman” who “looked after me like a mother.” When Jessie passed away, she lamented the passing of a friend of fifteen years, writing “I cannot imagine what I shall do without her.” She went on to employ Mrs. Saville, who cooked the elaborate meals that fed the dinner guests that made their rounds. While Power did consider her housekeepers as genuine friends, as Wade argues, the fact remains that “her intellectual freedom depended on the labor of another woman,” made possibly through an income.

Same-sex companionship was vital to the lives of the five modernist women of Square Haunting. Each of them, to varying degrees, decided against traditional, middle-class marriage and opted for more ambiguous relationships that were often premised on deep intellectual exchange and emotional companionship. Of course, sometimes middle-class matrimony and same-sex relationships were not entirely exchanged, but instead existed in parallel, as was the case with Woolf, who had a long-term marriage with Leonard Woolf, but also had a romantic relationship with Vita Sackville-West.

Yet, it would be incorrect to position these extra-marital relationships purely through the prism of elicit sexuality in retaliation to the shortcomings of men. As Wade writes, women “who enjoyed relationships with [other] women which could not so easily be mapped on to the template of heterosexual marriage”; likewise, these relationships cannot easily be mapped as a rejection of heterosexual marriage.

In the early twentieth century, a vocabulary for lesbianism was yet to exist. Bryher, born Annie Winifred Ellerman, the daughter of a shipping magnate, and H.D. used coded language to refer to their relationship, which lasted over forty years: in public, for instance, they would refer to one another filially, as cousins. In her autobiography, Harrison referred to Hope Mirrless, her pupil turned long-term friend and collaborator, as her “ghostly daughter,” which as Wade describes, “[hints] at the complex layers to a relationship which cannot easily be defined.”

When H.D. gave birth to a daughter, Frances Perdita, in March 1919, Bryher, became a crucial figure in H.D.’s journey into motherhood, and the continuance of her literary career. Bryher’s affluence enabled H.D. to avoid becoming overburdened by domestic responsibilities. In many ways, Bryher was the sort of mother that Power described Jessie as; following a traumatic birth and suffering due to influenza, “Bryher nursed H.D. loyally through this period and [through] subsequent crises.” Bryher paid for Perdita to be a resident at the Norland Nursey in Kensington for the first two years of her life. Later, Perdita would recall Bryher picking her up just as H.D. began to sharpen her pencils – signaling the transition to work – and shutting the door to the study. Bryher’s assumption of caring responsibilities was essential to H.D.’s ability to be both a mother and a writer without having to sacrifice one or the other.

Mirrlees was a constant companion of Harrison in the last thirteen years of her life. They worked alongside one another, lived together, and intermingled with Russian emigres fleeing the civil war in Paris together. Harrison and Mirrlees translated the seventeenth-century memoir of Avvakum, considered the first Russian autobiography. At the Mozart Avenue apartment of two Russian friends, Alexei and Seraphina Remizov, they drank tea and vodka as they labored over the translation, which was published by Hogarth Press in 1924. Harrison and Mirrlees’ lasting relationship was built around joint cultural production.

For the women of Square Haunting, companionship animated their creative work and intellectual pursuits. Often, these relationships were nourished through the rented flat – yet as much as the latter gave space to a rich social life, it could also be a site of heartache and emotional turmoil. The boarding room, in breaking down the dividing line between public and private, threatened to throw into the limelight extra-marital affairs and betrayal. In 1916 at 44 Mecklenburgh Square, H.D. began to feel the walls close in around her. The “merged bedroom and living room” threated to expose private affairs. In an act that Wade characterizes as “self-obliteration,” H.D. offered up the rented room to Aldington and the American women with whom he was having an affair, Arabella.

The move to London allowed one to become an urban spectator, and a participant in the dynamism of a city undergoing significant change. In the interwar years, laws and norms shifted, giving women more political and economic standing: in 1918, women’s suffrage became law (only to women who were over thirty years old and owned property); the 1919 Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act democratized professions that were previously only open to men; and schools and colleges, whose doors were previously shut to women, were cracking ajar. Women were stepping into the public sphere, and exercising their political voices through social activist movements. In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf describes London as an open-air workshop: “London was like a machine. We were all being shot backwards and forwards on this plain foundation to make some pattern.” The shooting backwards and forwards, together, was part of the appeal of moving to London in the first place.

For all of these modernist women, the transition from the stuffy family home to a rented flat, or room in a boarding house, prefigured their foray into public life as intellectuals, academics, and novelists. While a flat in a boarding house was often cramped and musky, it also signaled a world of possibility. As Victoria Rosner argues in Modernism and the Architecture of Private Life, modernism and the reformation of private life have twinned histories. While Harrison lived her later life in Mecklenburgh Square, spending her final day in her flat there, the other women of Square Haunting eventually moved on, and moved elsewhere. With destruction looming over the city, no boarding house was immune from wartime destruction: the drone of airplanes overhead was a reminder that war threatened to destroy the very conditions for cultural production that they had all sought. In time, Mecklenburgh Square – a site where ambitious novels and unforgettable characters were authored, a site of parties and deep intellectual exchange – could no longer be spared. In 1940, a time bomb exploded in Mecklenburgh Square, “bringing down the ceiling of the basement room which housed [Hogarth Press], blowing several doors off their hinges, breaking every window and all of the Woolfs’ china.” A few yards away, Harrison’s former home, 11 Mecklenburgh Square, was reduced to “a great pile of bricks.”

[1] The 1928 Equal Franchise Act, which enfranchised women over the age of twenty one, irrespective of property ownership

Lizzie Tribone is a writer currently based in London. She is interested in politics and visual culture, and has been published in The Appeal, The American Prospect, The Baffler, and BOMB, among others.

This post may contain affiliate links.