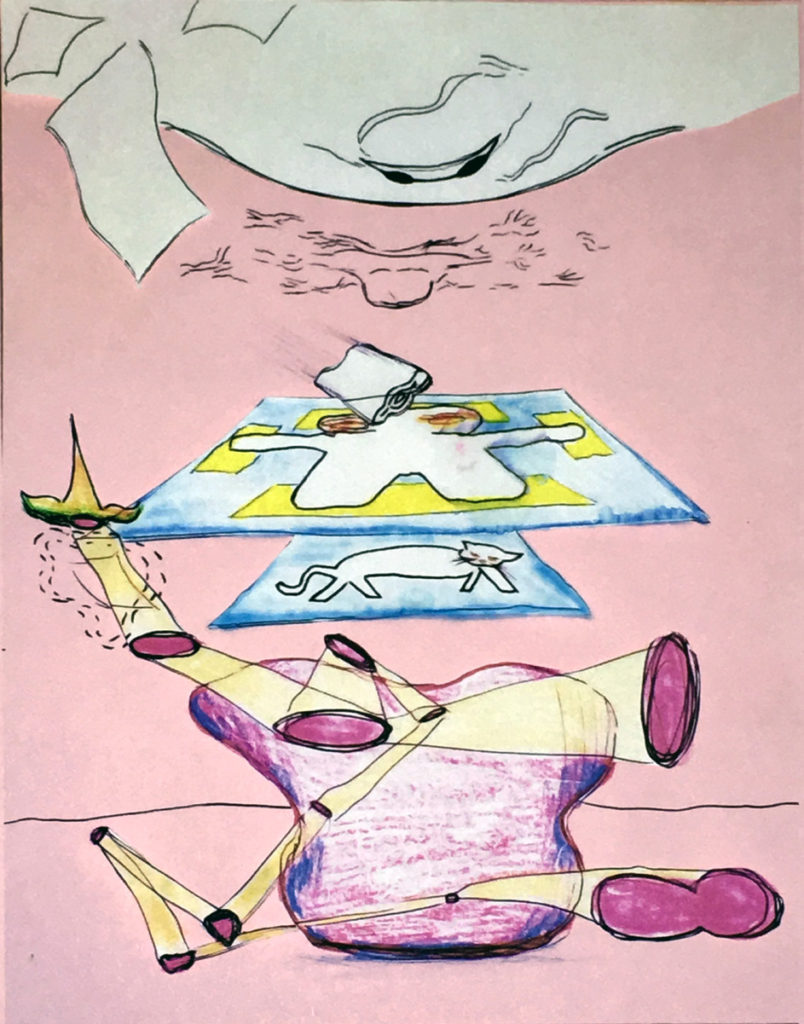

“Mic My Crotch,” by Daniel Genoves-Sylvan

This essay first appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly, Issue #9. To help us continue to pay our writers, please consider subscribing.

I often find myself sitting opposite the huge Thinx ads for menstrual underwear, plastered all over the subway in New York, featuring an open grapefruit and clean font: simple, vulvar, modern, antiquated. Lately, ads for SmartJane have populated my News Feed on Facebook, requesting send-in swab tests to discover your vagina’s particular pH cocktail. Another grapefruit, slit open—this one less juicy. My birth control bottle warns against eating grapefruit: “grapefruit and grapefruit juice decrease the breakdown of estrogen in the body . . . Although the increase in estrogen shouldn’t make the pill less effective, it could potentially increase the risk of side effects like blood clots and breast cancer.” Somehow in the effort to thwart my own grapefruit’s fruiting, I have been prevented from its consumption—which feels meaningful, if not ironic. The grapefruit-as-vulva is proliferated as both medical and sensual, from euphemism for hygiene marketing to the strange new sexual practice of grapefruiting. This split from the-thing-as-represented from its purity and its taboo is a common theme when it comes to fruit and sexuality. Take the cherry: red, juicy, clefted. It is at once the schoolgirl’s uncompromised virginity as it is her seductive wickedness—her cherry-stained lips, how she can tie the stem into a knot with her tongue. While the cherry must be intact, the grapefruit could hardly serve its vulvar purpose without being cut in half—after all, it isn’t the melon known to represent breasts, whole and round. Iconography is never without its rich and troubled code.

The fruit of sex/sex of fruit is ubiquitous. There are the ads for sexual health by the NY Department of Health: a screenshot of an eggplant emoji sent as a salacious text with a “Get Tested” imperative. Or the shiny poster for Hims, the millennial erectile dysfunction company, of a flaccid cactus flopped over in its terracotta. I’m thinking about pineapple juice, the vindication of the fruited cum, the G-Eazy “little momma let me see you move /and I might go down / let me taste that mango.” Didn’t we all squeeze our fruit at the farmer’s market a little differently after the peach scene in Call Me By Your Name, in which the young Elio masturbates into a peach that his older lover Oliver subsequently attempts to eat? If a man orders champagne for the two of you, it’s just an indication of a celebration. If it’s champagne and strawberries, it’s almost certainly not platonic. Our correlation of fruit and sex extends far beyond the sex-ed class banana, and into our conception of the illicit.

Fruit itself is the enlarged ovary of a flowering plant. It both disseminates seeds and contains them within, and thus can do well as metaphor for the inseminator and the inseminated. In Greek and Roman mythology, Agdistis was a deity possessing both male and female sexual organs. The nature of her intersex made her threatening to the gods—fearing her, Dionysus spiked Agdistis’ wine, and tied her foot to her own penis. Unknowingly standing up upon waking, Agdistis ripped the organ from her body. It is said that the blood that spurted from her wound fertilized the ground, from which a pomegranate tree sprang. When the daughter of a river-god discovered the tree, she placed a pomegranate between her breasts to carry it home, and instantly became pregnant with the god Attis. The pomegranate is not the fruit of permittance; it appears in more than one story of a woman’s body as battlegrounds. “The Rape of Persephone” is depicted as having precipitated when she ate pomegranate seeds, the fruit of the Underworld, and was seized by the desire of Hades. There are fruits that take from us as much as they give.

In the Bible, “bearing fruit” means the products (words, deeds, thoughts) of one’s soul. God’s people must ‘bear much fruit’ (John 15:5, 8). There are two kinds of fruit the soul can produce: fruits of the spirit and fruits of the flesh. One can surmise which of the two is the virtuous. But which fruit isn’t of the flesh?

Christ’s parable of the fig tree emphasizes that, spiritually speaking, a fruitless fruit tree is worthless (Luke 13:6-9). “A certain man . . . said to the keeper of his vineyard, ‘Look, for three years I have come seeking fruit on this fig tree and find none. Cut it down; why does it use up the ground?’ But he answered and said to him, ‘Sir, let it alone this year also, until I dig around it and fertilize it. And if it bears fruit, well. But if not, after that you can cut it down’ ” (verses 7–9).*

Fruit is not only good, but compulsory for continued existence. It gives and creates life. The woman must bear the fruits of her womb, as the man must espouse the fruit of his loins, and yet some fruit is not to be eaten. Certain fruits perpetuate our fall—that infamous and eternal serpentine apple. Or not an apple at all—it is believed by many ancient and Biblical scholars to have been a fig or pomegranate. When Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit, they laced fig-leaves over themselves to cover their shame. The fig itself not only has strong sexual connotations in Western art as the inner sanctum of a woman (the word for fig in Italian, fica, also means ‘pussy’), but its very existence is rife with the drama of sex. The fig plant has two types of figs: edible female figs, and male caprifigs. Figs and fig wasps have a symbiotic relationship in which their mutual survival is dependent upon the other—the wasp must enter the fig to lay its eggs, just as it was born in it. If a female wasp enters a male caprifig, she will find the interior parts perfectly suited to her egg-laying. She will then fly off, carrying with her the pollen that reproduces the figs. However, should she enter the female edible fig, she will die of exhaustion or starvation.† We do not eat the male caprifigs full of baby wasps, but we do eat the edible female figs that often house the broken-down protein of a female wasp’s body. In her attempt to “bear the fruit” of her womb, the wasp is consumed by the fruit that was the wrong one—And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, “Of every tree of the garden you may freely eat; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.” Yet, she did deliver the pollen—if she didn’t, what would happen? (‘Look, for three years I have come seeking fruit on this fig tree and find none. Cut it down; why does it use up the ground?’). There will be more figs to eat, forbidden or otherwise, and more fig leaves with which to cover one’s shame. The figs you eat have the bodies of the dead who tried to enter those to whom they are the same rather than those to whom they are different—Leviticus tells us such things are an “abomination,” and this fruit is your caution as it is your knowledge. If we think of knowledge as the progeny of the procreative fusion of two things with different information (biological or otherwise); its metaphors are sibling to sex. And just like sex, it deals in power and the forbidden.

We pass through myth and meaning as swiftly as we pass through trend and significance. What was once the most forbidden of the sexual fruits is now nearly defunct in our euphemistic playbook; now dominated by eggplants and peaches. Even body types flux in and out of mode (are you an apple or pear shape?)—what was once the “does this make my ass look big?” hand-wringing of the late 90s and early aughts is now the “These 5 Squats Will Get You as Bootylicious as Nicki!” listicle. A fascinating anthropological read is 15 Reasons Focus Has Shifted From Big Boobs to Big Butts, in other words, from the melons to the peach. A study of a 1,618 random tweets over a twelve-hour period by Emojipedia discerned that 33 percent of people were using the peach emoji as “shorthand for butt,” and 27 percent of people were using the emoji sexually. A mere 7 percent meant it for its literal interpretation as fruit. When Apple rolled out the iOS 10.2 update, there was outcry—the peach emoji had been reimagined as less contrasted, less . . . erotic. Apple responded to the clamors of the people and returned the peach emoji to its former “gluteal glory.” We need our signs and signifiers. How else will we represent ourselves; our desires and urges, the nectar running down our chin?

The relationship between sex and fruit survives as our offspring, the fruit we bear, do: through adaptation, reproduction, and consumption. It changes as our desires change, as ancient as it is contemporary. In the end, our culture bears the fruit of the seeds we sow it with.

Koby L. Omansky is a Brooklyn-based writer who works in youth advocacy. Her work has been published in Skin Deep Magazine, The Establishment, anthologies by Platypus Press and Thoughtcrime Press, and more.

This post may contain affiliate links.