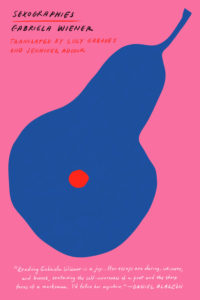

Tr. from the Spanish by Lucy Greaves and Jennifer Adcock

At the beginning of one of my favorite essays from Sexographies, Gabriela Wiener’s first collection in English, the Peruvian writer announces the death of Latin America’s best-selling and most-famous woman writer:

On the afternoon of September 24, 2012, Isabel Allende died, and all the women who felt like they’d known her all their lives, as if each line that sprang from her pen had been written for them especially, lit scented candles on their bedroom altars and placed magic crystals around their copies of Eva Luna.

Characteristic of Wiener’s witty and irreverent style, readers could be forgiven for assuming that the essay would be another tired critique of Allende, written by a young Latin American woman writer struggling under the anxiety of influence.

But it turns out that Allende is not dead, the announcement is only a Twitter hoax and the perfect hook for Wiener to begin an insightful reflection on Allende’s legacy and literary significance. This is done through a magazine-style profile in which Wiener follows Allende around Mexico City as they attend a conference on “the intellectual experience of women in the twenty-first century.” As is typical in Wiener’s writing, which has been compared in style to the gonzo journalism pioneered by writers like Joan Didion and Hunter S. Thompson in the United States in the 1970s, the author herself appears as a self-satirizing protagonist in the essay. This allows her to both lovingly mock Allende — “she’s a beloved female figure I’d hate to become. It might be the silk scarves, long earrings, and shamanic aura” — as well as engage in a not-so-subtle critique of the literary critics, who she acknowledges she has often aligned herself with, who believe “that the most widely read author in Spanish is a bad writer.”

Particularly delightful are her take downs of the writers who love to hate Allende’s writing — “Making fun of Isabel Allende isn’t a sign of intelligence, it’s part of Latin American literary folklore” — and her sly comment on the signature style of “serious” (read “male”) twentieth-century Latin American literature: “Try writing from the bottom tip of the American continent about emotions and sex instead of tunnels and labyrinths.” While such pithy one-liners like this are peppered throughout Sexographies, they don’t detract from Wiener’s more serious aim, which is to provide a nuanced reflection on gender, writing, and the literary marketplace. She manages to balance a critique of the “cheapness, lace, and frills” of Allende’s work at the same time as recognizing the writer’s socio-cultural significance; especially within the context of the historical prejudice faced by the women writers of Allende’s generation, writing under the long shadow of the Latin American literary Boom of the 1960s.

One of the most-telling anecdotes Wiener includes in the essay relates to when Chilean poet Pablo Neruda tells a young Isabel Allende that she is a terrible journalist: “You’re incapable of being objective, you put yourself at the center of everything, I suspect you lie a lot, and when you don’t have news you make them up.” Whereas Neruda’s advice encourages Allende to abandon journalism and take up literary fiction, where such features would be considered virtues not defects, Wiener’s own writing — which could also be nicely summed up by Neruda’s description — brazenly challenges such a purist distinction between the literary and the journalistic, in the same way that she contests the “high” versus “low” categorization used to disregard “women’s” writing.

Wiener is one of the boldest voices of a new generation of Latin American writers experimenting in the field of literary journalism or creative nonfiction — referring to works of nonfiction that adopt the techniques of literary or creative writing. The form has seen somewhat of a renaissance in recent years, particularly in the United States, and within the Spanish-speaking world there has also been a resurgence of literary journalism over the last few decades. Termed crónicas — the name deriving from the chronicles which recorded the conquest of the Americas — the genre has an established history in the region and was used influentially by writers throughout the twentieth century to comment on the major social, political, and cultural changes affecting Latin American societies. In the work of the masters of the form, such as Carlos Monsiváis, Elena Poniatowska, and Gabriel García Márquez, the crónica became a powerful tool to explore urban life, modernity, and class struggle, as well as to denounce political repression, human rights abuses, and state violence.

In the twenty-first century, critics have argued, the new wave of cronistas have continued to concentrate on urgent socio-political themes, for example Leila Guerriero’s work on forced disappearance, Óscar Martínez and Valeria Luiselli on migration, and Diego Enrique Osorno on the drugs war, amongst many others. However, their use of the form has also been characterized by a more varied focus on the idiosyncrasies of daily life, identity, and sexuality; influenced by contemporary forms of pop culture and social media. If the late-twentieth-century chroniclers are synonymous with political writing during the era of the Latin American military dictatorships, the new cronistas display a more plural, less overtly political, stance that engages with the multiple demands of the neoliberal, post-dictatorship era.

The sixteen essays that make up Sexographies illustrate how Wiener’s writing dialogues with this context and traverses the boundaries of genre and gender, politics and pop culture, quickly extrapolating from the personal to deeper, social commentary. Born in 1975 in Lima, she grew up during the internal armed conflict in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s, and from 2003 has been based in Spain where she has worked as a journalist. The essays included in the English-language collection published by US press Restless Books come from three collections of crónicas: Sexografías (2008), Llamada perdida (2015) and Dicen de mí (2017).

Although Wiener’s prose is often marked by a flippant tone, as indicated by her essay on Allende, behind this lie traces that touch upon darker themes such as violence, migration, and marginalized bodies and identities. The essay entitled “From This Side and from That Side” is a reflection on living between two cultures, Spain and Peru, in which the narrator is burdened by both the traumas of past political violence — “It was not unusual to come across photographs of dead bodies during the 1980s in Peru. I was obsessed with dead bodies, especially those that came in black plastic bags” — and the violence of present economic inequality: “I came to Spain because I was told that my destiny awaited here, in this so-called Europe. The crisis was supposedly ‘affecting’ Europe, but Spain wasn’t just ‘affected,’ it was a wasteland.”

Transnational migration is a theme which permeates this collection and is present in two of its most moving essays, “Trans” and “Goodbye, Little Egg, Goodbye.” The first is an exploration of the double marginalization of Latin American trans people, forced to migrate due to repression at home, and who then find themselves working as undocumented sex workers in Europe. Wiener questions the absurdity of the multiple borders that determine people’s lives: “Not long ago, the police arrested Vanesa in the woods because she’s — what? trans? a sex worker? an illegal immigrant?” In the second essay, the author immerses herself in the world of private fertility treatments and egg donation in Spain to explore the racial and gender hierarchies underpinning the fertility industry: “I’d interviewed for an article about donating eggs. They were all young Latin American women like myself”; “The majority of clients in these clinics are Caucasian Europeans.” In both these essays, Wiener demonstrates her ability to extrapolate from her own personal experience to tell a story with universal, albeit often-unknown, significance.

What is most powerful about the collection is Wiener’s audacious and immersive style, skilfully captured in English translation by experienced translators Lucy Greaves and Jennifer Adcock. Like the gonzo journalists she is compared to, there is no pretense at objectivity. The author fearlessly throws herself into what the reader would regard as uncomfortable, or even risky situations as part of her quest to provide faithful and honest accounts of personal experience. In these essays she not only undergoes the arduous process of egg donation and hangs out with sex workers in the woods outside Paris, she goes to a workshop where she has to live her own death, documents a trip to the Amazon to take the hallucinogenic plant Ayahuasca, researches tattoos in one of Peru’s most dangerous prisons, spends time living with an infamous sex guru and his six wives, takes lessons from a dominatrix, and visits a swingers’ club in Barcelona.

Much of her work, as can be seen from this description, is concerned with transgressing the limits of sex and sexuality. She declares: “I’ve always been a firm believer in not having limits, especially when it comes to sex.” Alongside experimenting with BDSM and going to a swingers’ club with her husband, in the essay “#Notpee” Wiener researches female ejaculation, going on a quest to find the “Great Orgasm”; whilst in “Three” she muses on infidelity, threesomes, and transgressive sex, declaring “I’ve been unfaithful to everyone I’ve ever dated.” Wiener is brutally honest about sex, about her sexual desires, her nonconformity and risk-taking, and it’s refreshing to hear a female voice able to speak so honestly about subjects still considered a taboo for women.

This doesn’t just apply to Wiener’s sexual experiences, which are documented in minute detail with footnotes in “Planet Swingers,” but to broader realms of female experience and subjectivity. Her writing is engaging because it doesn’t simply flaunt her erotic freedom but embeds this in an extremely frank dialogue with the reader in which Wiener reveals her own flaws, anxieties, and neuroses. She rejects monogamy but struggles with the complex emotions polyamory and open relationships provoke: “It’s initially as unpleasant as using a stranger’s toothbrush. Watching someone you love have sex with someone else.” Most poignantly in “The Greater the Beauty, the More It Is Befouled” she details the relationship between her sexuality and her struggles with body dysmorphia disorder, “I worry obsessively about things I consider to be defects in my physical appearance.” The collection thus conveys a profound honesty about female sexuality that goes beyond a simple defense of sexual freedom to expose the complexities of desire, the body, and psychology.

Wiener is a good writer. She also knows how to consistently elevate her engaging, chatty style to the higher heights of more literary expression — as in the description of Monique the dominatrix, “One of Monique’s eyes is as gelid as the eye of a fish” — or meta-literary commentary, “Vanesa, who really should be featured in an anthology of Latin American dirty realism, can jolt you out of anything.” However, at times Wiener’s personal narrative, her intense desire to document experience and put herself in extreme circumstances to unveil some deeper truth, actually seems to take precedence over that deeper truth itself. In some of the essays this is illustrated through taking a familiar subject without making any new, or more profound, comment on the topic. For example, in “A Trip Through Ayahuasca” Wiener travels well-worn territory as she follows in the footsteps of William Burroughs, and numerous other Westerners, to take the Amazonian plant-based medicine ayahuasca. Although hinting at the problematic commodification of the sacred plant — “Increasingly, shamans are taking ayahuasca to big cities, traveling by plane throughout the world at the summons of rich people” — the essay really fails to delve into a deeper exploration of the contemporary meanings of the practice and its appropriation by the western world. Here, like in other essays, such as “In the Prison of Your Skin”, Wiener seems overly focused on her own experience without showing clearly why this story is significant or what universal implications it has. The best long-form narratives are thoroughly-researched, immersive stories, which make us ask broader questions about the world we live in. I’m not sure that Sexographies always achieves this and at certain points it feels that Wiener is more concerned with shocking the reader than making them reflect.

Nonetheless, Sexographies is a promising example of how Latin American cronistas are experimenting with literary journalism. Wiener is welcome addition to a talented crop of new, Latin American women writers who are changing the literary scene and being picked up by innovative independent publishers of writing in translation like Restless Books. We need more writers like her who are willing to bravely explore the uncharted realms of experience, sexuality, gender, and identity. And we definitely need more writers like her in English translation.

Cherilyn Elston is a lecturer in Latin American Cultural Studies at the University of Reading, UK. She is the author of Women’s Writing in Colombia – An Alternative History (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016) and the translator of Jorge Consiglio, Southerly (Charco Press, 2017). She is the managing editor of the online literary translation journal, Palabras Errantes: http://www.palabraserrantes.

This post may contain affiliate links.