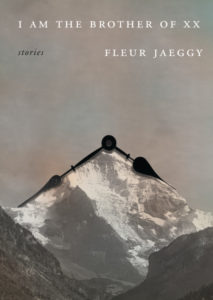

[New Directions, 2017]

[New Directions, 2017]

Tr. by Gini Alhadeff

A narrator (Joseph Brodsky rendered in his original Russian Iosif) feels “that Baltic quality of air, expecting snow.” It is a cold winter in New York, and the chill reflects the narrator’s interior state: “Every place is to him a mental city called Negde, which in Russia means ‘nowhere.’” Iosif sits on the Promenade and enjoys the “stealthy disquietude” of this atmosphere — “It’s nice to sit on a bench and think, with a feeling of reciprocity, of the void.”

In Gini Alhadeff’s translation from the Italian, Fleur Jaeggy, who is Swiss, displays a remarkably concise, pared-down style, one for reciprocating with voids. The sentences are terse and elliptical, but with crystalline beauty. No word seems unnecessary, each one seems chosen precisely for its evocation of mood, atmosphere, temperament. In these stories, most of which are vignettes and are only the length of two or three pages, there is no plot as such, no psychological sense of character development. I might call Jaeggy’s style a gothic minimalism. There are traces of menace here; a sense that what you see is not all. Inhabiting these stories, compressed and distilled without excess description of setting or a character’s motivations, is like knowing you are alone but sensing a dark shape’s movement that isn’t there by the time you turn.

Jaeggy’s thematic concerns are death, theology, and love (familial, especially) in its poisoned, contorted forms. The title story has a brother denouncing his sister, who he refers to as XX, on the first page: “How was I to know there was a spy at our table. A big old spy in the house.” This sister is seven years older and guilty of writing about her brother. Perhaps, because we learn very quickly that we’re not sure whom to trust. To be honest, the whole family is suspect. The family plot is untenable. Can the unit survive without anyone turning on each other? Impossible. Each of Jaeggy’s spare sentences lead onto the next without giving the reader a clear picture of the narrator; what emerges then, is a glimpse of a person with multiple layers of complexity. Lesser writers might write pages of description depicting a character’s so-called psychological growth and still present their readers with a stereotype. In Jaeggy, it’s the bare minimum of information and a glimpse of the mystery, the deep chasm. This brother-narrator’s way of thinking is startling and alluring: “Words have a weight. Importance is weightier than solitude. Though I know solitude is harsher. But the importance of succeeding in life is a noose. It’s nothing but a noose.” Jaeggy depicts the world of a ruined bourgeois family via the brother of XX and his contemplation of his relatives and his own position, but there are no pablums in these pages. He recalls that his grandmother had once scalded herself with hot coffee and carried on as if nothing had happened: “And so if in our family we don’t even know when we’re burning like logs in a fireplace it can only mean that our bodies abandon us, that maybe we are spirits, and it’s not clear when we stopped being ourselves and became something else.”

“The Last of the Line” is the story of a doomed bourgeois family and the uneasy implication of dead siblings haunting its every sentence. There is a sense of wretchedness, of moneyed people having come to ruin through something coursing through their blood that in this case, leads only to death and seclusion and withdrawal. Caspar, the “last of the line,” in a house “built like a fortress, isolated from the rest of the village, and isolated in the mind of the rest of the world.” In this fortress, Caspar does some thinking: “Death, he had decided, makes prisoners of us.” We are never told how his brothers Anton and Stefan died. We wait for the inevitable haunting, but not even Jaeggy’s ghosts are simple creatures. The story ends, revealing no resolution or insight. It is like peering through the window of a house one evening out of curiosity, catching a glimpse of something unnameable yet foreboding, and wishing that you never looked.

Yet another disturbing child features in the chilling “The Heir.” Hannelore is an orphan, whom the rich and lonely Fraulein von Oelix has taken on as a companion. The opening lines of the story are a capture of Jaeggy’s style:

Hannelore, a girl without a fixed residence, is the only witness to a fire in the apartment of Fraulein von Oelix. A modest, gray afternoon. Vitreous. The fraulein is a kind woman, wilted and very lonely. And solitude had made her even kinder, she practically apologized. Lonely people are often afraid to let their solitude show. Some are ashamed. Families are so strong. They have all of advertising on their side. But a person alone is nothing but a shipwreck. First they cast it adrift, then they let it sink.

It is not long before we are in Hannelore’s head: “What does thinking matter? Thinking is iniquitous. It is not pleasing to God. Creation is a form of destruction.” Jaeggy is adept at this fluidity of interchanging perspectives; the effect is not confusing for the careful reader, but disorienting. In these brief stories with only two central characters at most, Jaeggy mimics what life is like when multiple voices are trying to convince you of several different things. This is not free indirect discourse for the purpose of unravelling the hypocrisy of bourgeois civility and its social codes, but to reveal the terrifying core that exists in people: the private self will not be saved by rationality.

Dead mystics appear in “The Visitor,” as Angela da Foligno suddenly appears in the halls of the Archeological Museum in Naples. Then a fresco of the birth of Venus begins to register her presence. “The fresco is tinged with the void. The curious gaze of the goddess visits the museum’s other guests.” In Jaeggy’s story, the goddess and the mystic do not meet and present a revisionist version of world history as kick-ass female characters. No. Instead, “The ascetic and the goddess touch lightly.” Instead, the goddess is wrestling with an existential issue, that of the simulacrum of herself: “The goddess saw herself repeated, reflected in many museums. She cannot tell herself from the copies.” When the Nymphs step out of their representation, there is only blank terror: “Now they remain outside, outcasts, forgotten by everyone. They thrash about in search of their ghosts.” Jaeggy brings up the void, again and again, in gentle, almost affectionate and yearning terms. Jaeggy’s stories are an attempt to give the void a language. As she says in this interview in TANK, “I’m very, very much for nothing.”

Ingeborg Bachmann shows up throughout the collection. The final story, “The Salt Water House,” is also about Bachmann, and carries a premonition throughout its sentences, though it is one of the lightest stories in the collection. Chronicling a vacation taken together with Bachmann when they were , Jaeggy writes lovingly about Bachmann’s preference for not having to participate in social niceties, the way her voice conveyed “timid resolve.” Roberto Calasso is mentioned here as Roberto Calasso, “ a friend of Ingeborg’s” before he became Jaeggy’s husband. Italo Calvino is here, whose silence has to be broken before conversation is permitted: “We had agreed: if he doesn’t speak, we don’t speak.” Perhaps it says something about Jaeggy’s vision, that the one story about a friend who died is the one that is bittersweet and delicate, a celebration of people existing together. In another story for example, togetherness is a premonition of something potentially toxic, especially if it’s borne out of desire or romantic love: “Since then we became inseparable. Like an illness.” But in the story about Bachmann, togetherness is a hint of something sweet, a promise of true communion between two misfit souls.

Subashini Navaratnam has written elsewhere for Full Stop.

This post may contain affiliate links.