Guy Delisle’s previous books chronicled his life as an expatriate in Asia and the Middle East. In Pyongyang, Delisle describes his life as an employee of an animation studio that outsources its grunt labor to North Korea. He lives in a cold, sheltered hotel, where his minders refuse to tell him anything that could threaten their livelihoods. He can only sense oppression from an unsettling distance. Empty streets. Robotic smiles. A friend who nervously returns him a copy of 1984. In Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City, he describes his life as the husband of an employee of Doctors Without Borders. He can sense the tensions in the city, but he never sees the brutality of the Gaza War firsthand. Delisle casts himself as an amiable, unpretentious Westerner who commits one faux pas after another. He knows a little more about himself and the world after his excursions, but only so much more, and hardly enough.

Guy Delisle’s previous books chronicled his life as an expatriate in Asia and the Middle East. In Pyongyang, Delisle describes his life as an employee of an animation studio that outsources its grunt labor to North Korea. He lives in a cold, sheltered hotel, where his minders refuse to tell him anything that could threaten their livelihoods. He can only sense oppression from an unsettling distance. Empty streets. Robotic smiles. A friend who nervously returns him a copy of 1984. In Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City, he describes his life as the husband of an employee of Doctors Without Borders. He can sense the tensions in the city, but he never sees the brutality of the Gaza War firsthand. Delisle casts himself as an amiable, unpretentious Westerner who commits one faux pas after another. He knows a little more about himself and the world after his excursions, but only so much more, and hardly enough.

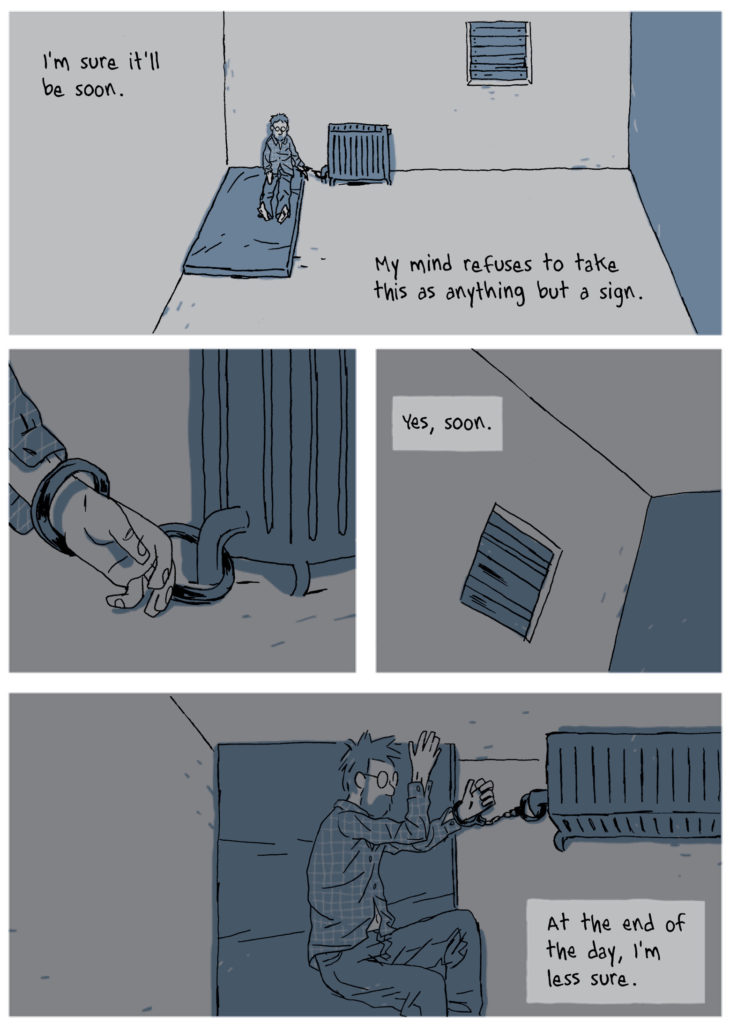

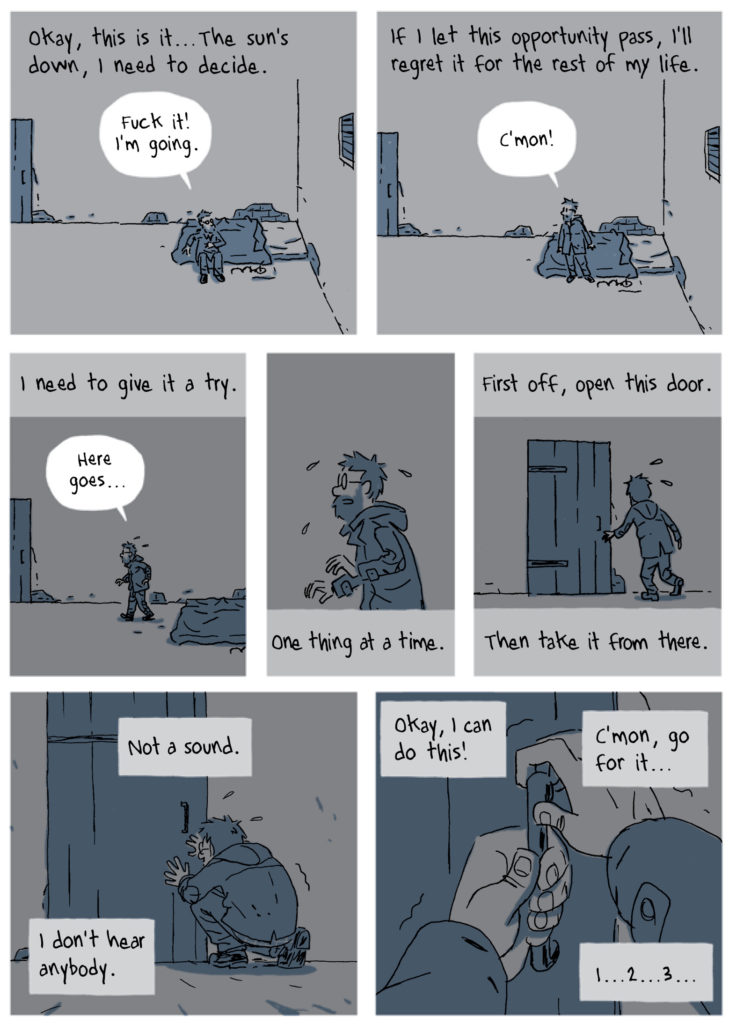

Hostage marks a major departure for Delisle. The book tells the story of Christophe André, an employee of Doctors Without Borders who was kidnapped and held for ransom in Chechnya in 1997. Delisle worked with André to piece together a chronology of the doctor’s life in captivity and his daring, successful escape.

I spoke with Delisle by phone on April 19.

Paul Morton: In your books about Burma, Shenzhen, Pyongyang, and Jerusalem, you are always one step removed from violence. Atrocities occur, but almost always off panel, in the gutter. What was the biggest challenge for you when it came to depicting violence in Hostage?

Guy Delisle: There were many differences between this book and the others. There is no humor. I’m not in there. I’m describing someone else.

There’s no physical violence. It’s just a slow, mentally-based [torture], because [Christophe] is stripped from his freedom and he has no control over his life. So that’s kind of a torture, but, fortunately, he was not physically abused while he was there. Otherwise, I don’t think there would be a book about it.

[Christophe] said that to escape was therapy. That’s why he was so open about it when I first met him.

This is the longest graphic narrative I can think of that takes place in a single room for most of it. There are a lot of movies that do the same, recently Room, but also Lifeboat and any number of adaptations of plays. Did you look to those films to develop any strategies?

No. I saw Lifeboat a very long time ago. I didn’t see Room. I saw part of it on the airplane. Movies are very different from comic books even though they look alike. I kept my drawing very simple. It’s a real-life story. The more you put special effects in a real-life story, the less it’s going to look like a real-life story. It’s going to look like a Hollywood blockbuster. I didn’t need to reference movies that are so different.

I’ve read a few books about people who have been kidnapped to try to see if there were similarities between the stuff they were thinking. But they didn’t go that much into thinking. I had Christophe right in front of me and so I could ask him how did he feel at that moment.

Which books did you read?

There’s one by García Márquez about people who have been kidnapped. [News of a Kidnapping]. Another one about a Mexican guy. I didn’t read the whole thing because like Christophe says, every kidnap story is different from one to another. Some are with other people so they have nothing to do with what Christophe has been through. Some have no chance to escape. The fact that he escaped changed the whole situation. Because he escaped he didn’t feel as a victim. He became stronger after the story than what he was before.

Does the simplicity of the drawing style come because you are depicting a more psychological battle between a man and himself?

Yeah. I wanted to use a technique that was easy to use, kind of a sketchy line that had that fragile feeling.

Did you struggle with any ethical issues when you were working on this book?

Well, no. It was just me and Christophe André. There was no censorship from Christophe because we just adjusted a few things here and there.

I don’t go through politics, because I don’t explain the situation in Chechnya. It would have been a very long book if I were to explain the situation. And for me it was not so important, because I was most interested in the kidnapping. It happened in Chechnya, but for me it could have been Colombia. It would have been the exact same story.

You said the book is mostly about psychological torture and it is, but being handcuffed all day to a radiator is physically very painful.

Yes, but as Christophe was telling me, he was not beaten, like they do sometimes. Or they pretend they’re going to execute hostages just to freak them out. They didn’t do that. They were just people who were paid to feed him just like an old dog you would give to your neighbor. They were not really bad people.

I’ve noticed that you tend not to draw scary people as scary. I’m thinking of the racist settler in Jerusalem. I don’t like him, but you don’t make him look very ugly. Is that just one of your tics as an artist?

Maybe that’s just because that’s how life is. Scary people, they don’t look so bad. They just look like normal people. And once you get to know them a little bit, then they might scare you.

But that’s coming from Christophe. He was telling me about these two guys, the tall one and the fat one. He had no animosity towards them. They were just there because they had no choice. They were just there. They were part of a family or a clan. And some people brought him there and said, “You are going to keep this guy.” That was it. That’s how it works over there in Chechnya.

Does this book reflect in anyway how your thoughts about being an expat have changed?

Well, somehow it links to the other books. It talks about the NGO people in the Burma one especially. And then when you get to travel to North Korea you get to see the amount of freedom that people have. When I left North Korea and I said goodbye to these guys, I left them thinking that there will be no way I can contact them and I’m not going to be able to see them again because they can’t leave their country. And when you go back home you think about freedom a lot. Same with Burma. Freedom was there as a theme in my books. And in this one it is the main subject.

To be completely deprived of your freedom. That always has fascinated me. And yeah, being around humanitarian people. They all tell you a lot of stories that they have experienced. And a lot of them are very exciting and very exotic. But the one from Christophe is a bit different because it’s a story that I can relate to. Because being kidnapped is something that could happen to anyone if you travel a bit. It’s just a matter of being in the wrong place at the wrong moment. It’s just no luck at all.

Paul Morton has worked as a cultural journalist in Vietnam, Bulgaria and Latvia. He also completed a Fulbright fellowship in Budapest, where he researched Hungary’s communist-era animation industry. His interview with Marvel Comics writer Brian Michael Bendis appeared in Ultimate Spider-Man: Ultimatum. He currently lives in Seattle where he is a Ph.D. candidate in Cinema Studies at the University of Washington. He can be reached via email at[email protected]. You can also read his blog My Thought-Dreams.

This post may contain affiliate links.