Tr. by Megan McDowell

“In exercises 25 through 36, choose the answer that puts the sentences in the best possible order to form a coherent text.” Thus begins the second section of Alejandro Zambra’s Multiple Choice, a novel, which I had good reason to suspect would frustrate more than stir my interest. The instructions are followed by a series of statements:

- You group them into two lists: the ones you love and the ones you don’t.

- You group them into two lists: the ones who shouldn’t be alive and the ones who shouldn’t be dead.

- You group them according to the degree of trust they inspired in you as a child.

- For a moment you think you discover something important, something that has been hanging over you for years.

- You group them into two lists: the living and the dead.

The task is absurd. The statements lack logic, causal connections, and thereby a coherent or objective sequence. I was gripped, you see, with an all too familiar anxiety: what if it is my judgment, my capacity for critical thinking rather than this question that is flawed? This is, perhaps, precisely the point Multiple Choice makes. Coherence and logic are not inherent to human experience. Life is paratactic. Causality, the root of arguments and anguish, is the product of a rigorous and motivated training.

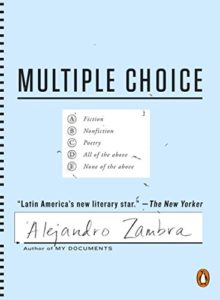

The structure of Multiple Choice is based on the Chilean Academic Aptitude Test, which students took in December each year from 1967 through 2003. The book specifically takes the form of the Verbal Aptitude test (as it was given in 1993, the year the author took the exam), which consisted of ninety multiple-choice exercises presented in five sections: excluded term, sentence order, sentence completion, sentence elimination, and reading comprehension. Admittedly, I feared the book would exhaust its novelty within the first several pages. I did not imagine that a narrative would accumulate, that the form, far from deflating or disrupting narrative immersion, would add a layer of tension, and would itself perform one of the novel’s more salient points: namely, that such training is motivated and structures not only our decision making, but the narratives we tell, and by extension our sense of — hardly! — respective selves.

I. Excluded Term

Initially, the narrative elements are sparse. The novel opens with the section Excluded Term, wherein readers are asked to eliminate the word whose meaning has no relation to the others. The first term is multiple. The choices are as follows: A) manifold, B) numerous, C) untold, D) five, E) two. Initially, the list of words—with the exception of one, which readers are asked to eliminate — are either synonyms, exemplifications, or literal translations of the primary term. Yet, as the section progresses, the choices become increasingly — though slowly and subtly — subjective. Rather than providing the primary term’s literal meaning, the options seem to spring from feelings or ideas, which it invokes. So, the gradual progression from denotative to connotative meanings performs the ease with which “objective truths” slide into political biases and allegiances. In other words the aim of such exercises is not to teach, as Zambra plainly states later in the novel, but to train and to train the pupil not simply to perceive reality a particular way, but to feel a particular way about such perceptions. The final term, for instance, in this section is silence. The choices are A) fidelity, B) complicity, C) loyalty, D) conspiracy, E) cowardice. Yes, the test taker is explicitly asked to eliminate no more than one word. Yet to do this properly requires many to sweep away whole webs of relations that have been woven through singular contexts and individual experiences. Such experiences are not quantifiable, are therefore wrong, and thereby counted as nothing. Indeed, elimination and erasure are major themes that recur throughout the novel. The mini-narratives chart the accumulation, the erasure, and the shaping of history, both personal and national, in the production of a legible self.

II. Sentence Order

The second section opens with a series of relatively laconic entries. The reader is asked to order them as a means of achieving coherence. Of course, as is apparent in the opening example, the statements hold few clues concerning the chronology of their unfolding:

- Nineteen eighty-something

- Your father argued with your mother.

- Your mother argued with your brother.

- Your brother argued with your father.

- It was almost always cold.

- That is all you remember.

Though the section instructs test takers to order the statements sequentially, the statements that follow are impervious to the linearity which history imposes on lived experience. The shift from statement to statement is more akin to the perpetual flow of consciousness, or the abrupt transition from one scene to the next characteristic of memory and the fragmented manner in which it returns forgotten time to us. If these passages are absorbed in the act of remembering, then they are equally haunted by the act of forgetting. The mini-narratives perform both the triumph of memory over contingent time as well as the triumph of time over memory. As the section progresses the entries grow increasingly protracted, sometimes spanning several pages. As themes recur from passage to passage, an identity begins to collect around the second person pronoun, and there is something quietly mournful about the tone the piece takes. Perhaps, it is the way both past and present narratives possess a melancholic resignation, as though time must be quietly endured, as if, like the test, the future is fixed. You have already lost.

III. Sentence Completion

The section titled “sentence completion” asks the reader to complete a series of statements, the missing elements of which primarily reflect the speaker’s emotional relation or reaction to the statement’s content.

- You were a bad son, but ___. You were a bad father, but ___. You are alone, but ___.

- people vote for you

people vote for you

people vote for you- I love you

I love you

I love you- I’m not your father

I’m not your son

that’s not my problem- you know it

you know it

you know it- no one knows

no one knows

no one knows

The options range from the trivial to the tragic. Though they’re frequently contradictory, far from reading the answers as mutually exclusive, I read them each as equally contributing to the section’s purpose. The section reads a little like a monologue, wherein the speaker seeks the clause that will eventually absolve him. Nevertheless, he is continuously thrust back into the circuit of his own guilt, just as the reader is repeatedly thrust back upon the string of accusatory clauses.

- You were a bad son, but ___. You were a bad father, but ___. You are alone, but ___.

- you’re happy

you’re happy

you’re happy- it’s hard to be a son

it’s hard to be a father

we are all alone- a good soldier

a good Christian

Jesus is with you- your backhand is amazing

you lent me sixty bucks man

you have a good time- your mother died so long ago

your son died so long ago

you want to be alone

Like many questions in the section, the statement appears again in countless variations. The tone ranges from cantankerous to conciliatory, impassive to palaverous, and ultimately offers readers a sampling of the many defensive styles we adopt when faced with our own shortcomings. Many of the themes (father/son relationships, a critique of the Chilean Constitution, a critique of the University) touched upon and turned over thus far will be further elaborated upon in later narratives, lending these seemingly disparate motifs greater coherence.

IV. Sentence Elimination

In the fourth section, readers are asked to indicate the sentences or paragraphs that can be eliminated because they do not add information or are unrelated to the rest of the text.

(1) A curfew is a regulation prohibiting free circulation in the public space within a determined area.

(2) It tends to be decreed in times of war or popular uprising.

(3) The dictatorship imposed one in Santiago, Chile, from September 11, 1973, until January 2, 1987.

(4) One summer evening my father went out walking with no destination in mind. It grew late, and he had to sleep at a friend’s house.

(5) They made love, she got pregnant, I was born.

Narratively speaking, the first three entries could be read as providing context for what follows. The reader, however, is given the option of eliminating either the top three entries, or eliminating the bottom two. The task, therefore, does not so much entail one to designate the unrelated entries, but rather to designate a point of reference, to which everything else must be related. As the questions progress, and the entries increase in length, it becomes more and more difficult to select which paragraphs can be cut, especially since the individual paragraphs themselves possess such a delightfully digressive aesthetic. For instance, when the speaker states that no one in Chile speaks in elevators, and adds that they share their “fragility in silence, like a sacrifice,” one might ask whether the lonely mood this digressive and poetic description projects contributes necessary information to the overall passage.

V. Reading Comprehension

The final section, titled “reading comprehension,” ironically and obsessively takes up the theme of forgetting or erasing that which we cannot comprehend. The section is comprised of three first person narratives, whose respective topics are cheating on high school exams, a nullified marriage, and a reluctant father’s somewhat defensive apology to a son. Each of these themes were taken up, in far more fragmented form, by previous sections, and so, the final section, lends a satisfying sense of coherence to the novel. The opening narrative begins:

After so many study guides, so many practice and proficiency and achievement tests, it would have been impossible for us not to learn something, but we forgot everything almost right away and, I’m afraid, for good. The thing that we did learn, and to perfection — the thing we would remember for the rest of our lives — was how to cheat on tests.

Zambra offers, as one option among the five possible morals, that learning how to cheat gradually shapes students into productive individuals who contribute to Chilean society.

The student’s illusion that he must retain information is itself, as the passage suggests, one of the many tricks of the Aptitude Test. Cheating is the only valuable lesson school imparted. And this lesson, as it extends beyond the classroom, suggests something about the process of socialization in general. First, the pupil is trained to operate within a system, next the student is assimilated into that system, and finally, while adhering to the social codes that render them inconspicuous, they must learn to make the system work for them.

“The bride — of course I remember her name, though I think eventually I’ll forget it.” Thus opens the second text, wherein the narrator tells of his first marriage and its eventual dissolution. Since divorce, at the time of this marriage, was still illegal in Chile, the couple is forced to annul their wedding. Annulment, unlike divorce, requires the couple to insist their marriage never existed. “Now that I think about it,” the narrator concludes, “the best way to summarize our story together would be that I gradually annulled her and she me, until finally we were both entirely annulled.” The sentiment, or belief that erasure, annulment, forgetfulness is innate and, perhaps, a human necessity is echoed in the final narrative, wherein a father addresses his estranged son. “Pay no mind, my son,” he writes, “to what I tell you; pay me no mind at all. I hope that time, in your memory, will mitigate my shouting, my inappropriate remarks, and my stupid jokes. I hope that time will erase almost all of my words . . . And you could even decide, for example, if it were necessary, to erase me. . . . That’s what life consists of, I’m afraid: erasing and being erased.”

Jessica Alexander is a PhD candidate at the University of Utah. Her work has appeared in such journals as Black Warrior Review, Denver Quarterly, and Fence. She is currently a fiction editor for Quarterly West.

This post may contain affiliate links.