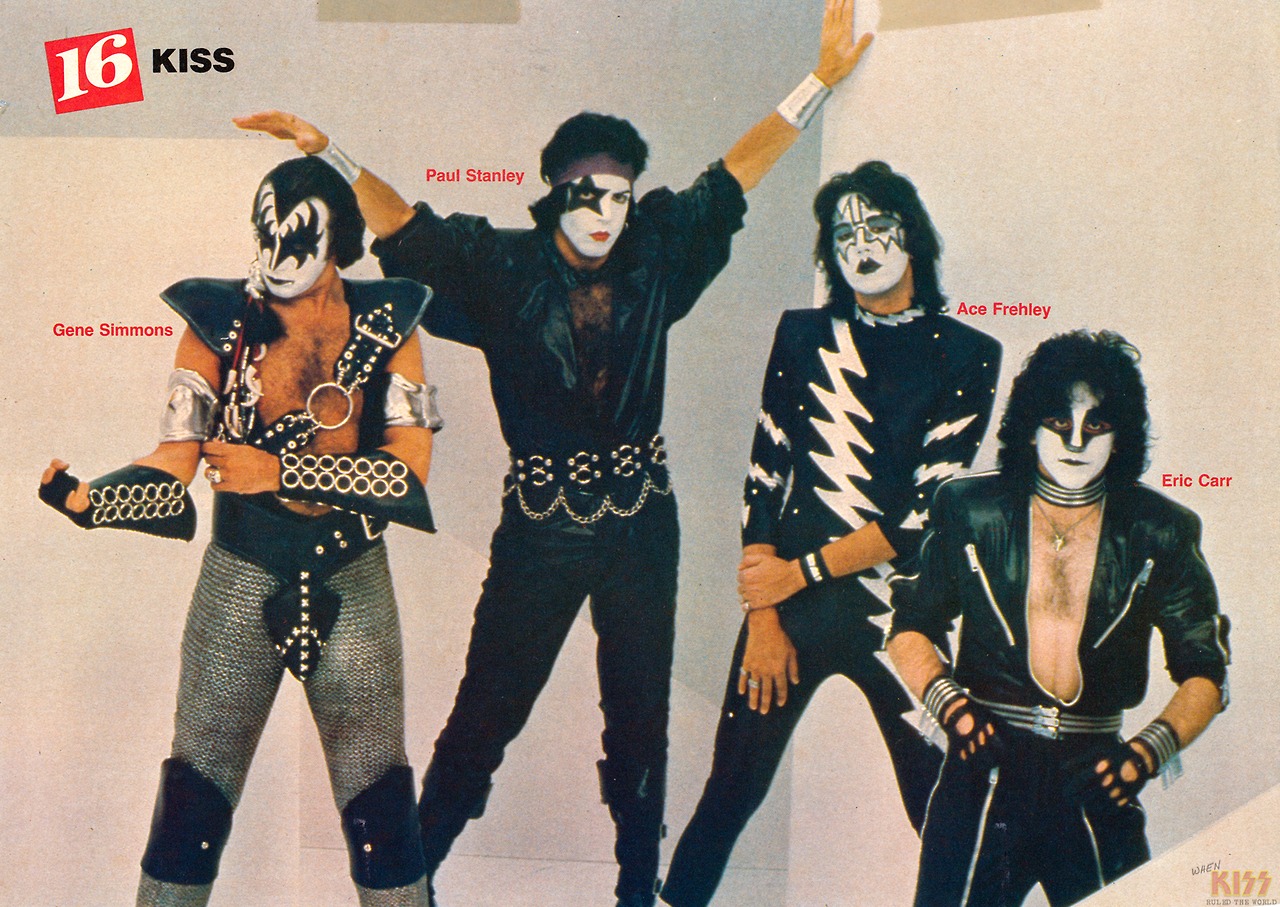

Gene Simmons, serpent tongued bassist and front man of glam rockers KISS, was recently interviewed for the Esquire culture blog by his son Nick Simmons. I know nothing of Nick other than that he is Gene’s son, I don’t know what his agenda or career entails, and I won’t be finding out for the purposes of this post. I’m not interested. Like Esquire, I’m interested in his dad, and in this interview his dad succinctly says that Rock is Dead, the internet killed it, and if only we had held on to the dream of free market capitalism everything would still be grand.

Gene Simmons, serpent tongued bassist and front man of glam rockers KISS, was recently interviewed for the Esquire culture blog by his son Nick Simmons. I know nothing of Nick other than that he is Gene’s son, I don’t know what his agenda or career entails, and I won’t be finding out for the purposes of this post. I’m not interested. Like Esquire, I’m interested in his dad, and in this interview his dad succinctly says that Rock is Dead, the internet killed it, and if only we had held on to the dream of free market capitalism everything would still be grand.

Before I address these claims, I think it’s necessary to outline Simmons’ politics. I last had cause to think of Gene Simmons when he appeared on The One Show on BBC 1. For those who don’t know, The One Show (the title of which seems more unsettling the more I write it) is an early evening light talk and magazine show. Two affable hosts gently rib each other in the way that people describe as “chemistry” while introducing a variety of segments on a range of topics including: oddities like childhood hedgehog watching clubs in rural Yorkshire, usually something that helped save lives in WWII, and darker territory like systemic abuse of children in the care system of a provincial British town. A well-meaning guest, there to plug their addition to the slew of celebrity hardbacks or their new documentary about cheese production, is expected to comment on each of these stories with equal enthusiasm. This often creates awful television, as many guests are reasonably forced into a loop of sympathetic sighing and others have egos so large they lunge aggressively into topics on which they clearly know very little. This is how Gene Simmons came to be asked, after promoting something, maybe a KISS coffee grinder, if he had any suggestion to resolve the chronic understaffing in the National Health Service. His solution was to open it up to the market. In fairness, this may indirectly resolve the staffing issue, as the public at large, based on examples in other countries, would not be able to afford medical treatment.

He is a right of center fellow.

Some of what he says in the interview is not incorrect. Labels that used to be somewhat supportive of artists in building a career (though this is challenged by the experiences of many) have become even more exploitative, if you can get them to sign you at all. However, he goes on to set himself, his work, and what he considers to be rock in a false dichotomy with dance, rap, and pop music. Rock has creators, he argues, these other styles are part of just another industrial production process.

There is a lot wrong with that statement. It seems to have escaped Simmons’ attention that his success has been predicated on making Rock as Pop, which it is anyway, but KISS is Pop Rock in extremis.

Simmons is right to suggest that there is something of a crisis of cultural production. Since most of it can be digitized, stolen copies of records, photos, TV shows and movies flood the internet and become the bête noire of content publishers and some producers, like Simmons. But what I found really odd in the interview was that Simmons sees this as a problem caused by middle class people not sufficiently understanding how capitalism is supposed to work. He says:

My sense is that file-sharing started in predominantly white, middle- and upper-middle-class young people who were native-born, who felt they were entitled to have something for free, because that’s what they were used to. If you believe in capitalism — and I’m a firm believer in free-market capitalism — then that other model is chaos. It destroys the structure.

This is a startlingly confused statement to be published in a major magazine, even in its online format. File sharing may have been an invention of the middle classes, but it can now be practiced by anyone with an internet connection, which is a lot of people. What’s more, by many measures, the disposable income of the middle class in North America and much of western Europe has been decreasing over the last thirty years as neoliberal policies have come to define late capitalism. Simmons’ remarks on the NHS in the UK made the argument that the market would reduce the costs of services. I would argue that what we see in the case of file sharing is the result of a market mechanism, part of what Marx saw as capitalism’s capacity to spur innovation.

In a post-Fordist society we all become responsible for the maintenance and appreciation of our human capital. Cultural capital, some of which is accrued through a familiarity with current and important pieces of cultural production, forms a part of the human capital metric. It greases the wheels of communicative capitalism. Unfortunately, your precarious working arrangement barely covers the essentials, like the internet connection you need to find your next temporary position, and records are so expensive. They may well be the first thing to cut from your budget when market forces push down your wages. Just in time, someone comes along with an ingenious invention and the entrepreneurial spirit to see it through and make a dollar in the process. And, as Nick Simmons reminds us, in the good old days punters “voted with their dollar.” Now the overdraft stretching pub conversations that are the origins of all good start-ups have cultural the resources to begin with ease rather than: “Hey have you heard that new band? They’re great.” “No, I have no money.” “Oh, that’s cool you can listen on my Walkman while I awkwardly watch your reaction.” File sharing spares us this horror.

The market works. Except it doesn’t. Simmons thinks producing music should allow you to become a millionaire by garnishing the modest incomes of the public. In response to the world created by this ideology, people have developed a system for the accelerated consumption of music that has not allowed time for ethical question of how the labor of cultural production should be rewarded. To this I have no answer, and it is unlikely that there will ever be one entirely adequate answer.

Simmons theorizes that this is all because the native born Americans don’t have a sense of the value of hard work, based out of the romance of his own particular immigrant American dream story. He thinks that those born American don’t know what hard work is and thus don’t respect the capitalist system. This reminds me of a section of David Foster Wallace’s novel The Pale King, in which an IRS worker makes the provocative argument to a captive audience of colleagues that what they are experiencing as the “me first” culture of the mid-80s has its origins in the protests against the Vietnam war. That when protesting the war became fashionable it gave credence to individuals’ decisions to put themselves before national duty. The logically absurd undercurrent in that section of the novel — that not wishing to sacrifice yourself to an imperialist military folly led to the apathy that made room for the conservative revolution of the 80s — is delivered by Simmons as the common sense of his argument.

Simmons is the front man of one of the most heavily merchandized bands to have ever existed, he has made everything he produced into product, and more precisely into commodity. Like toilet paper or cornflakes. I believe that, if Adorno had lived to see them, KISS would have given him a stroke. Can Simmons really blame the consumers of the capitalist society he so loves for hunting for a bargain?

Macon Holt is an academic cultural theorist, writer, and musician. He writes a monthly column for Full Stop on pop music as a utopian political project.

This post may contain affiliate links.