[Semiotext(e); 2017]

[Semiotext(e); 2017]

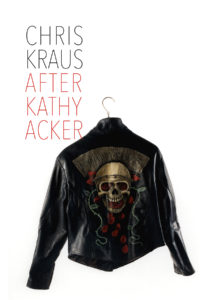

You can’t come to a book like Chris Kraus’s biography of Kathy Acker without certain expectations. Following the resurgence of interest in I Love Dick (1997), Kraus is now a household name whose name rightly or wrongly will forever be associated with the kind of personal essay that nowadays passes for cultural criticism, in which the I, imperial, absorbs all within its purview. Given Acker’s renown as a writer whose experimental work blurred the boundary between fiction and memoir, if you know her work at all you’re likely to have some ideas about what a biography of Acker should look like — were it true to her style. If you’re familiar with both writers; if you know they moved in the same Downtown New York/West Coast circles or the fact that for a time they both fucked and loved the same guy (Sylvère Lotringer), you’ll also anticipate moments of rivalry, sympathy, empathy even.

So there’s a lot going on before you even open the book. Kraus, a nobody during Acker’s lifetime but now an author with fame comparable or even in excess of hers, is acutely sensitive to the expectations of her readers and Acker’s: our preconceptions are a powerful fog that envelops the work and pre-empts its revelations; which threatens to supplant it or take it over. Kraus is plainly aware of this — she’s spent too long in the company of artists on both coasts not to be cognizant of how aura can precede and displace artworks themselves. In After Kathy Acker she negates our expectations, offering a biography somewhat by the numbers that isn’t introspective or experimental, and is hardly revealing at all of her acquaintance with Acker. All of this should add up to a rather underwhelming reading experience; the fact that it doesn’t has to do with how Kraus engages with Acker’s myth, breaking it down and renewing it in ways that echo Acker’s own practice. In her life and writing, Acker engaged in experiments that allowed her to constantly fabricate new identities for herself: Kraus’s book in some ways builds on this endeavor, constructing yet another version of Acker.

The book opens with Acker’s wake and the scattering of her ashes in San Francisco, after her death from cancer in a Mexican alternative treatment facility in November 1997. By far the most intricately plotted part of the work, the narrative jumps around a lot, moving back and forth between the funeral ceremonies in the present and Acker’s final days. The erratic organization of scenes seems to limn something of Acker’s friends’ grief and the difficulty of arranging or accurately recalling memories in sequence: “like everything in the past,” runs the opening line, “everyone remembers it differently and some of the people involved hardly remember it at all.”

This opening section also contains one of the very few instances in which Kraus herself speaks in the first person. She writes:

Around this time last year, when I started working on what may or may not be a biography of Kathy Acker, I imagined beginning the book with the melee at Slim’s Bar, or at the wake, where a group of friends gathered to transfer her ashes from a box to an urn, or at the scattering. To describe these proceedings would be to stage an establishing shot of a movie that uses a single protagonist to traverse an entire milieu.

This is the kind of Kraus her readers expect — one that uses the first person singular to lever open a whole can of critical reflections: how the work was composed, where she stands in relation to it, what other media it employs, which ones it evokes, etc. Yet this characteristic Krausian style appears only one or two more times.

From the first section on, the initial desultory arrangement also disappears, giving way to an increasingly chronological sequence of events. Kraus begins by describing Acker’s early attempts to become a writer in the ‘70s and details her participation (with Len Neufield) in a Times Square sex show called Fun City (scenes from this show would find their way into Acker’s writings and become mythic in her retelling). On moving to San Francisco in ‘72, she met Eleanor and David Antin, artists who played a pivotal role in her development as a writer. With David Antin’s encouragement Acker went to the library and started copying out passages from other books, splicing them with her own diary-entries in a practice of appropriation for which she is now best known. Acker started self-publishing as The Black Tarantula, mailed out copies of her chapbooks to a list of artist-acquaintances, got positive responses, and her career started to take off.

In these opening chapters, Kraus separates myth from reality and a portrait of Acker begins to cohere. First and foremost she is restless, moving to-and-fro across the United States in a pattern that would persist throughout her life and ultimately send her farther afield to places like London and Brighton. She’s industrious, too, and highly driven — pushing herself to write every day without exception. She dearly “craves” fame, we’re told. She’s pretty highly-sexed but often lonely. Sometimes, she’s obnoxious: the kind of person you’d invite to stay with you before a poetry reading, who’d then turn up five weeks beforehand with her boyfriend in tow expecting a bed. (She lasted only two weeks at Bernadette Mayer’s place before Mayer finally threw her out.) She’s also a liar:

Acker lied all the time. She was rich, she was poor, she was the mother of twins, she’d been a stripper for years, a guest editor of Film Comment magazine at the age of fourteen, a graduate student of Herbert Marcuse’s. She lied when it was clearly beneficial to her, and she lied even when it was not.

Kraus appears to have no time for this tissue of lies, however. Even Acker’s novels are picked apart for biographical material, undoing her careful weaving together of fact and fiction, which Kraus disassembles in the pursuit of truth and reconstitutes as a coherent narrative of a life without embellishment.

After Kathy Acker thus presents a portrait of Acker for a generation of readers that are far more receptive to notions of writerly sincerity and expressions of an “authentic” authorial self than they are to post-structuralist concepts of, say, schizo-culture or desubjectification (ideas Acker repeatedly experimented with). Kraus’s Acker is one calibrated to the contemporary moment and is portrayed as a vulnerable, somewhat lost, and not always likeable female artist desperately trying to make it in the world. Not all that surprising, then, that a blurb by Sheila Heti, the author of How Should A Person Be?, acclaims the emergence in the text of Acker as “an unlikely literary hero.”

This approach is not unproblematic. In Acker’s first book-series, The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, the text reads: “I want to blow my identity outwards, away.” In a 1991 interview with Sylvère Lotringer, Acker recalls that “I became very interested in the model of schizophrenia . . . The idea that you don’t need to have a central identity, that a split identity was a more viable way in the world. I was splitting the I into false and true I’s and I just wanted to see if this false I was more or less real than the true I.” Martha Rosler, quoted by Kraus, recalls that “Kathy’s whole persona depended on an endless series of reflecting, fictive personas, like a hall of mirrors.” Variously a puncturing of Acker’s expansive identity, a meticulous excision of her many false I’s, and a hammer taken to her hall of mirrors, in Kraus’s biography a single, apparently true, and rather sad Acker remains.

It’s not hard to see in this a massive FUCK YOU to Acker; to read an almost violent intent into Kraus’s rendering true and linear Acker’s experimental approach to selfhood — the way that the biography seems to put back together the writer’s supposedly authentic identity when she had done so much to falsify it, rid herself of it, reflect it into a million personae.

On the other hand, Kraus’s biography is less a matricidal undertaking and more a sisterly extension of Acker’s constant efforts to dismantle the self and remake it differently. Acker’s passion for bodybuilding is a good, rather literal, example of this. In “Against Ordinary Language,” an essay on weightlifting which takes the form of aphorisms penned in-between sets, Acker states that “muscles will grow only if they are, not exercised or moved, but actually broken down. The general law behind bodybuilding is that muscle, if broken down in a controlled fashion and then provided with the proper growth factors such as nutrients and rest, will grow back larger than before.” In her life and work, Acker was committed to breaking-down and reconstituting her identity: “Is the equation between destruction and growth also a formula for art?” she writes. Kraus’s biography affirms this commitment. After Acker in the sense of in her style or according to her model, the book continues to re-work and renew Acker’s identity after her own practice was cut tragically short.

What therefore seems from one perspective as an attempt to debunk the Acker myth is from another its expansion and regrowth: in addition to Acker’s already-abundant personae here we have yet another version that is more personal, less certain of herself, more palatable to a contemporary audience. In conversation with Lotringer, Acker said that while writing Empire of the Senseless (1988), “I became very interested in myths. What I tried to do . . . was to start to make a kind of myth that would be applicable to me and my friends”: in this work Kraus simultaneously unpicks Acker’s myth and re-creates it, making it applicable to a whole new range of readers.

Diarmuid Hester is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge. Find him on Twitter @dehester.

This post may contain affiliate links.