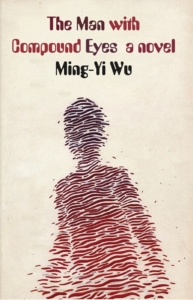

[Pantheon; 2014]

[Pantheon; 2014]

Tr. Darryl Sterk

“My father said there were two things in the world that would never change,” says Dafu, an aboriginal boy doomed never to be a hunter, “the mountains and the sea.”

This world is warming. I’ve known that since I saw it on the news aged six and cried the night away until my father promised me membership to Greenpeace. In the quarter-century since then, what has been done to solve this problem has been, in short, sweet fuck all. The seas are rising and there is less going back than there ever was. The tears of delegates from the Philippines at international conferences on the subject go unheeded year after year, mega-storm after mega-storm. It turns out Big Oil already plans to sell more than five times the amount of fossil fuels that would keep temperatures below the conservative two degrees estimated to be the limit of what our planet can afford. This is a disaster that has been happening for a long time.

The Man with the Compound Eyes, Taiwanese author Wu Ming-Yi’s first novel to be translated into English, was inspired by news reports concerning the Pacific Garbage Patch, a part of the sea where all of the rubbish which ends up adrift is drawn together by ocean currents. The novel describes a scenario, less than a decade into a very near and likely future, in which weather patterns disrupted by climate change cause such a trash vortex to collide with the coast of Taiwan, a coast the novel describes as having changed so quickly that migratory birds can no longer recognise it and become lost. The Man with the Compound Eyes is not about global warming so much as it is about what happens when things that have been thought to be constant begin to shift. It is about change on a scale that dwarfs human reason to the extent that it can only be experienced as loss.

All the narratives in the novel are articulations, on some level, of a struggle for certainty. A teenage boy named Atil e is born on Wayo Wayo, a mythical pacific island where, as a second son on an island that cannot support any population growth at all, his destiny is ritual suicide at sea. But instead of meeting death, Atil e is washed away by freak currents and into the trash vortex. He calls the trash island “Gesi Gesi.” “Gesi has a variety of different meanings but mainly it is used to describe what one does not understand,” Atil e explains to Alice, a Taiwanese writer and academic whose house is submerged in the deluge that brings the trash island to shore.

Gesi Gesi is “a place covered in incomprehensible things,” and apprehension toward the incomprehensible is a refrain to which Wu Ming-Yi constantly returns. The trash island is too multifarious to be knowable, yet it and the destruction it brings are also inevitable: it’s a collision between certainty and uncertainty, or perhaps between opposing certainties.

Atil e is impressively used by Wu Ming-Yi, not as a whimsical device or romantic affectation, but as a means of materialist critique. One character imagines the trash as the guilty conscience of capitalism coming back to haunt civilisation and Atil e could perhaps be understood as a personification of this idea. What are all these things and what are their meanings? His character is the means by which these questions are asked. To Atil e, the things he finds in the trash are mysteries, but to the reader they are everyday objects.

Thus, Atil e’s presence in the novel — his concocted otherness and his articulation of Gesi, his strangeness; arriving like a piece of trash himself caught up, by chance or destiny in the vortex — opens up this otherwise realist narrative into one which makes room for coincidence and synchronicity. He is not so much alien or extra terrestrial, but rather he functions as a control subject against which to compare other viewpoints. His world, Wayo Wayo, is an idealised world, as it might have been had the tragedies of the written word and colonialism never occurred. Capitalism is held to account here through Atil e but also and in a different way, by the aboriginal people of Taiwan, Dafu of the Bunum tribe, and Hafay of the Pangcah who seem (at least to this outsider, with little prior knowledge of Taiwan) clearly drawn from life. These characters, in contrast to Atil e, bring their knowledge and different tribal backgrounds to bear on the events at hand. Atil e is the mythical wise fool, his lack of context in this world creates a space. He is a construction that allows learning to occur.

***

In the last year or so the prevalence of speculative or science fiction dealing with the future of climate has been made much of. Referred to as cli-fi (a term coined by journalist Daniel Bloom), this emerging genre has been widely discussed in Western press, as well as in the English-language press in Taiwan. In an Oregon university there’s a whole course devoted to it, and in the UK, the organisation Dark Mountain has published five anthologies of writing about a future in which collapse is viewed not as a possibility but as a certainty. Science Fiction has always been perhaps the most ecologically aware of fiction genres — to create entire worlds with words the author has to be, perhaps, a keen observer of how the one which they inhabit actually functions — but it seems both likely and indeed fitting that preoccupation with such subjects should be increasing now.

What does sit uneasily is that the framing of this type of work as a discussion about the future denies the fact that the disaster to which it refers is, for many, already a reality. Reading a work like this in translation feels like a gift. Global warming is a global problem, but it does not affect the globe equally. In the last few months, refugees of climate change left their homes in the Carteret Islands of Papua New Guinea, where the water table has changed and left inhabitants with no way to sustain life there. To them, even the two-degree cap on warming was never a solution; the effects of climate change are not, for them, speculative possibilities but unavoidable, everyday fact.

Development has cost many indigenous populations everything, even before it was known what was happening to the atmosphere as a result of the same activity. The perspectives of people such as those of coastal Taiwan, on whom the pressure of survival under irrevocable change already falls, is very much needed to counter the apocalyptic visions of sudden collapse endlessly deferred that predominate in mainstream Western accounts. The translation of such perspectives into the English language is a political act, a challenge to the English-speaking world to witness the experience of those it has othered. In Wu Ming-Yi’s novel the description of Alice and Atil e’s efforts to learn each other’s languages is a touching reminder that communication across great divides is possible.

Thus, as was the case with the post-colonial controversy surrounding the term magical realism, the buzz-wordiness of cli-fi draws much needed attention to urgent trends but also has the potential to ghettoise an important discussion. In Liam Connell’s 1998 essay Discarding Magic Realism: Modernism, Anthropology, and Critical Practice, Connell develops an idea from Fredric Jameson, that the category of magical realism essentialises the literature of non-western cultures and that texts designated with the term might be more properly considered to be modernist. Connell suggests that the magical elements of both types of narrative are the result of attempting to describe the “disorientating effects of modernization.” He says:

It is paradoxically in this similarity that I would like to locate the difference. While both sets of writing are responding to the same occurrence — a rapid technological modernization — the material and historical conditions, and the relationship of power to that modernization, are irreconcilably different.

If the category magical realism creates a false subset of modernism, what is to stop the category of cli-fi from functioning in a similar way? What issue better exemplifies the effects of technological expansion than global warming? Narratives that challenge us to confront the reality of climate change may be being coded in ways that diminish understanding of their literary potential and lessen their impact. With this in mind I prefer to read across genre, as Wu Ming-Yi reads across his characters’ differing perspectives. The contradictions are as important as the resonances.

The writer Ursula Le Guin’s endorsement of The Man with the Compound Eyes notably avoids imposing categories on the work. The galley copy I have has her quote on the first page: “We haven’t read anything like this novel. Ever. South America gave us magical realism — What is Taiwan giving us? A new way of telling our reality.” I think she is right to make the distinction. Western press has described Wu Ming-Yi’s work most often in relation to the magical realism of writers like David Mitchell and Haruki Murakami, a comparison that I feel suggests an unwillingness to engage with the materialist concerns evident in Wu’s meticulous naturalism and archivist’s attention to detail.

I found The Man with the Compound Eyes more resonant with David Simon’s very realist TV narratives in the recently canceled Treme, which tells interlocking stories of everyday life in New Orleans after Katrina. The emphasis of both is on narrative and culture as political survival strategies and both seek to amplify the voices of those already doing this work. As Le Guin says: “Completely unsentimental but never brutal, Wu Ming-Yi treats human vulnerability and the world’s vulnerability with fearless tenderness.” Characterising Wu’s novel as magical or fantastical or concerned with the future, though not inaccurate, obscures its highly political and realist nature. It seems more appropriate to understand the novel as making use of a diversity of vocabularies with which to describe reality, many of which the West has historically alienated itself from (though that relationship is by no means symmetrical, as Wu’s novel opens with a quote from Yeats). This multi-valence is not diminished by Darryl Sterk’s devoted translation, which should be acknowledged as a layer of meta-narrative in its own right.

***

“What can you do?” asks Dafu, the titular man with the compound eyes. His father — a great hunter, on his deathbed — provides an answer: “become a man who knows the mountains.”

The characters of Wu Ming-Yi bear witness to the ecological predicament occurring around them in different ways, each of which is drawn subtly and with great sensitivity. Their stories are woven together, through the compound eyes of Wu’s omniscient, indifferent narrator, in a way that inspired in me some of the most potent relief I have felt in relation to this subject. This seems a paradoxical response given that the story, constructed as it is, from fragments of fragile yet vivid backstories, has such a radically harsh message at its core. The relief I feel in reading here is not escapist. It’s the relief that comes from facing up to fear and uncertainty, and from knowing that others are doing so too. The clarity that comes from admitting the worst. The fatalism with which the characters in The Man with the Compound Eyes respond to their situation is not, as with the defeatism of so many Western doomers, of disappointed romanticism. It’s the fortitude of those for whom climate change is not a phenomenon of the future, and of those who cannot afford to assume that the state will preserve something because they want it, because it never has.

Like the plastic in the sea, the human innovation of writing, of exterior memory storage, is here characterised as both enduring and toxic. Indeed, the effects of human activity embodied in the trash motif, the human production of memory (as storytelling, as history, as writing), and the meaningful tension between the two imply what has often been unsayable: the stories humans tell are not neutral; often they are preserved and protected at material cost to the continuity of other types of life. The novel teems with this life under threat. Every other sentence is an observation about fish or wild birds or the little cat that Alice calls Ohiyo — good morning — the reason she abandons her plans of suicide. Butterflies, mountain dogs, sea turtles: the patterns of these creatures’ movements, the certainties that come from observation of these patterns, unraveling inexorably as a result of human behaviour and yet somehow still part of a bigger picture, the one that only the man with the compound eyes can see and yet to which all beings contribute. Wu Ming-Yi is a naturalist as well as a storyteller, and it is perhaps his greatest achievement that this novel creates a sense of solidarity not only between his human characters, but also between these humans and the animals and plants he describes with such fidelity and with such inspiring belief in the reality of their wisdom and power.

Hestia Peppe is an artist, writer and sometime governess; a line tamer, a fire starter and a keeper of connections. She lives in London.

This post may contain affiliate links.