[New Directions; 2022]

The home page of Helen DeWitt’s website is given over to a note left for “Miss De-Witt” by “J. Collier” on a scrap of envelope. This Collier reports in careful all-caps spidery blue ink that a “fault in the underground cables” has made it impossible “to make calls out or to receive calls.” “When it is rectified. Is anyone’s guess,” muses Collier bleakly. “But it will be reported.” Emphasis mine here, but also, one senses, the writer’s, as Collier centers this determined final sentence on a line of its own and follows with a flourish of signature. This time-stained relic, with its misspellings and bleeding ink, has the qualities of a DeWitt story: colloquial liveliness, the texture of the real, existential plight, wry humor, and characters ranging from a utility worker to a staggeringly brilliant philologist (for surely the half-visible address on the envelope is that of the late great Anna Morpurgo Davies, professor of ancient Greek and Anatolian at Oxford, where DeWitt was herself a student of ancient languages). That DeWitt chooses this scrap of an envelope as the portal to her work online attests to the sly aesthetic of this tender connoisseur of everyday human predicament. DeWitt is an iconoclast, a rebel whose heart is with the young and the awkward, with the off-kilter ultra who feels more and knows more than anyone else at the game.

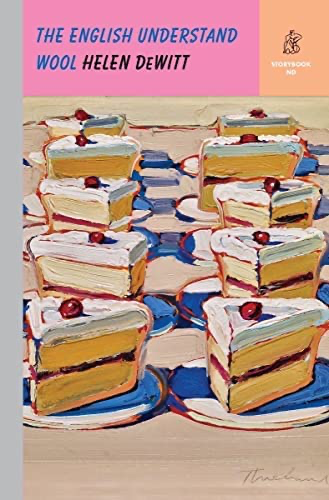

The English Understand Wool, DeWitt’s latest narrative offering, is one of the first of a new line of New Directions books curated by the writer and translator Gini Alhadeff. According to the publisher, these slim hardbacks are meant to recall, “the pleasure one felt as a child reading a marvelous book from cover to cover in an afternoon.” Such an afternoon, spent with a book curated by such an accomplished and worldly person as Alhadeff, seems of a piece of the life of Marguerite, this story’s precocious narrator, whose childhood is spent in English, French, and Arabic. As if tailor-made for this publishing venture, DeWitt serves up a tasty confection of a story (and indeed, the cover features Wayne Thiebaud’s thickly painted slices of Boston Creme pie—all the Storybook ND titles feature the work of art world stars).

Yet this long short story is also a lovingly hand-tipped poison arrow aimed for the heart of the elite culture in which it has found a home. In this, it is of a piece with her 2018 Some Trick, a collection about artists and savants and cranks coping with existential dissatisfaction. “If what I have is what I said I wanted / It’s not what I wanted,” she writes in that collection’s introduction. In “Brutto,” Some Trick’s opening story, an artist who finds herself admired and yet not able to support herself with the art she wants to make (a DeWitt theme that crops up again in The English Understand Wool) is offered a fantastic sum by an Italian art dealer for her Gesellenstück. “Gesellenstück” is German for a piece made for the culmination of an apprenticeship; as the narrator explains, in the sort of playfully instructive vein DeWitt often opens, it is “quite an old-fashioned word, maybe they don’t have it in English, to show you mastered the craft.” This particular Gesellenstück, a “baleful garment that no one would ever wear because of the hatefulness of the cloth and the cut and the straps and the stitching,” was made by the artist in her youth for the apprenticeship in dressmaking insisted on by her Nazi father. It was “locked up in a wooden coffin with no one to look at its madness,” until an “Italian guy” to whom she’d offered a cheese doodle at her art opening, wants it in his showroom in Milan—nineteen of them. The “Italian guy” turns out to be Adalberto, an art world tastemaker; the ugly suit may win our artist the coveted Turner Prize that her paintings did not.

The old-fashioned skill of dressmaking plays a key role in DeWitt’s new work, too. As the precocious narrator of The English Understand Wool explains, “suit” is not quite the right word in this story, either:

I use the word “suit” because I am writing in English, but the French tailleur—she [Maman] would naturally think of clothes in French—makes intelligible that one would travel from Marrakech to the Outer Hebrides to examine the work of a number of weavers . . . that one would bring one’s daughter, so that she might develop an eye for excellence in the fabric, know the marks of workmanship of real quality, observe how one develops an understanding with a craftsman of talent. The word “suit,” I think, makes this look quite mad.

That last sentence is a deft DeWittian turn: the “I think” is a decoy that mildly distracts from the sentence’s real work, which is to include the reader in the narrator’s rarefied world. By extension, we readers become joined to the story’s critique of the limits of the English language, the ruthlessness of capitalism, the hypocrisy of class, and the disappointing stupidity of those who affect the greatest public claims to intelligence (whether curator, agent, editor, bestselling author, etc).

Before these stories, DeWitt published two novels: the magnificent, exuberantly erudite, and darkly joyful Last Samurai — I’m among those who think it’s one of the best novels of the last couple of decades — and Lightning Rods, a novel that dares to spin an absurd and dark premise into a send-up of a “relatable” novel about contemporary office culture. Marguerite, the narrator of the new book, is, like Ludo in The Last Samurai, a precocious being whose understanding of the world far outpaces that of the adults who show up to facilitate her progress in the publishing world. As in Lightning Rods and the stories, any ordinary thing of contemporary life — a toilet stall, a cheese doodle, a Microsoft Word document — is as likely to become the carrier of plot and transformation as more elevated human efforts such as “a bolt of very beautiful handloomed tweed” or a Kurusawa film.

In some ways an extended riff on the artist’s observation in “Brutto”—that what “people can understand” is “the expense of materials, these things you can touch and see”—this new story shows Marguerite and her maman pursuing the finest materials imaginable, no matter the distance or cost; this is the source of the title and the book’s set-up. Maman is “exigeante—there is no English word.” Dropping names helps describe Maman (there is no English word for her): when in London, stay at Claridge’s; have installed a Yamaha Clavinova; when in Marrakech, order a Pleyel from Paris; join the riding club Les Cavaliers al-Hamra. (The Pleyel because “one wishes to play the piano-forte on the instrument preferred by Chopin.”) Maman is a woman for whom it is “quite simple to make brief visits to Paris from Marrakech” to see her Thai seamstress, from whom she may commission something like “a redingote in La Belle Assemblée 1815, a caraco of 1787, a three-quarter length coat in shantung with three-quarter length sleeves from 1962.”

As in this passage, throughout The English Understand Wool, DeWitt lays it on thick, like the artist in “Brutto” with her white “fat gloopy stuff,” like Thiebaud with his Boston Cremes. The seventeen-year-old narrator wears “a pale salmon shift in twilled silk” and “deep salmon half-d’Orsays of Italian leather with a modest 3-inch heel” while she orders a bottle of “the Puligny Montrachet” (to “accommodate” her editor, whose “tastes ran to white”). If this were all of DeWitt’s range, she would likely find some attentive audience of educated people with wine cellars and degrees and subscriptions to the New York Review of Books. But as that scrap of envelope on her website suggests, throughout her body of work, DeWitt attends to detail more democratically than this single story suggests. The same writer who describes Maman’s sartorial whims has a character sing “Poop Poop POOP poop POOP poop.” What is said about “the Estonian minimalist Liis Rüütel” in another story from Some Trick may be said of DeWitt herself: She has a “mastery of English” that means “she [can] articulate a point about the Kantian sublime and explain how to disconnect the water supply to a sink and then effortlessly use words like wally and boffin and bollix.” This extraordinary range from low to high is DeWitt, exactly. And her sentence doesn’t end there, she breathlessly comma-splices on this additional phrase: “if she wrote an advert on eBay to sell a toaster you were completely transfixed.”)With that comma and extra bit, she achieves a kind of reckless kinship with the excesses of our age’s many languages.

DeWitt famously has mastery of more than English — her extended author bio lists the fourteen languages that she knows, “in descending order of proficiency.” Add to that the languages of higher math and coding, too. In the character of Maman, DeWitt plays with a performance of this sort of extreme linguistic erudition. Maman speaks French “with a pure Parisian accent” and standard Arabic, “the Arabic of television, of high-level functionaries, of international businessmen, on formal occasions where French was inappropriate” as well as “Darija, the Moroccan form of Arabic, when the servants were ill or had family problems.” In this story, the mysterious Maman is not who she appears to be. Which is also to say that erudition is not what it appears to be. Wealth is not. Words are not. Her playful, deep excesses—the languages she draws from, the subcultures and trades she explores, the games she plays, the small details she brings to light—shake up our complacencies and broaden the range of our language. Sybilla, one of the two main characters in The Last Samurai, laments that the fate of the serious person is to be “writing thousands of words to consign to the dust and the dark.” Thank god New Directions has brought so many of DeWitt’s many thousands of words to the light.

Pam Thompson is the director of Bard College’s Clemente Course in the Humanities in Holyoke, Massachusetts. She is the author of the novel Every Past Thing and is at work on another novel, Wednesday Whale, or Unhappiness Risked.

This post may contain affiliate links.