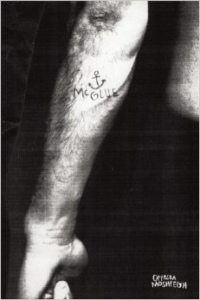

Caught stealing silver spoons, you can go to jail, or you can go to sea. Which makes a sailor out of McGlue.

Ottessa Moshfegh’s debut novel seems to use a classic plot driver: Johnson’s dead, McGlue stands accused. Does McGlue set about straightening the record? What record? Locked in the hole, McGlue is very hazy about what’s happened to him recently — only Johnson and McGlue go back much further than that. His shipmates insist: he killed his best friend. McGlue takes some of the air out of the Kafkaesqueness by appearing not to care either way. McGlue wants to be brought one thing, and that’s booze: will you go get him some?

Open on Zanzibar, McGlue puking on himself. There’s satisfaction in a historical novel that, without bells or anachronistic whistles, shakes off the yoke of authenticity. Don’t get me wrong: “I think, yeah, I’ll fuck it” sounds Five Points-y and totally nautical. But there’s something rather sly about this ode to a nineteenth-century Fleet Week wino. The effect is more pronounced given the kind of literary textures — McGlue is covered in a lush filth — at Moshfegh’s disposal.

I think of my mother as I imagine her always at the loom through the nailed-down windows of the mill, me a wee tip-toed kid, fingers hoisting my eyes barely above the horizon of the window ledge, watching my stoop-backed, prim, high-nosed mom at work, and watching her again that night at the table in our little house, calling me and brother “good boys,” pushing crumbs, counting coins and coughing, my sisters in bed already, my mother’s pale, tuckered out hair splayed across her back.

The details impress, though almost any one of them is overexplicit — the crescendo of Mom wearing her tiredness in her hair is the most on the nose and the most beautiful to me. Perhaps realness is always felt in spite of itself. Come to think of it, has there ever been a more enduring critique than that which presumes the priority of flash over substance? Which flavor do we prefer: when it’s directed at the current generation as a whole or just the one young culprit? Naturally, I’ve come to be moved by flash and agnostic on substance, so I mean it as a compliment: Moshfegh is flashy. When she decides to go long, the sentence careens through the entire paragraph; swooping, multiplying clauses in sustained bodily function: “all the cringey nerves and blood, swimming vessels puckered and empty and breath blowing for nothing and bones just creaking, mad, swaying like strained and knotted rope.” That McGlue manages not to exhaust itself is a testament to pacing — short stepping-stone sentences launching into the intestinal ones — and Moshfegh’s knack for all things tactile and olfactory. It’s this ornate style that accounts for one of Zadie Smith’s “Two Paths for the Novel.” In the essay — not quite as hostile to literary realism as they say — she dissects the profusely delicate passages of Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland, where “rinsed taxis . . . shone like grapefruits.” Of that particular still life Smith asks: “Grapefruits?” Ever since, whenever a physical description jumps the cartilaginous shark, I think, Grapefruits? How many distinct fronds in the tableau? (Grapefruits?) In fairly quick succession in McGlue, a description of facial hair as “wavering” and arm hair as “bristly.” (Grapefruits?)

Except there’s no way I’m saying turn off the tap. Though decidedly maximalist, McGlue prefers not to pull together threads from Moshfegh’s short fiction — the novel is a tangent in setting and a contraction of their concerns. Of her extant stories, I cannot readily describe their appeal. I want to say that I read them with some speed — what readers say to indicate pleasure that they can’t quite explain. Worse than that, I even want to say that I finished them, even though they were short stories. They’re that good. “Disgust” delves into the male psyche, a room with two pieces of furniture: longing and menace. The protagonist of “Bettering Myself,” come the season for performance-incentivized state tests, is jealous of the math teacher who took “all the kids who back in the Ukraine had been beaten with sticks.” She thinks, “Whenever anyone talked about the Ukraine, I pictured either a stark, gray forest full of howling black wolves or a trashy bar on a highway full of tired male prostitutes.” Funny, when I picture the shipping route around the Horn of Africa, I think about parrots on shoulders and oh God, oh God, if I should drown. End of list.

On the other hand, Moshfegh’s fiction converges in a sense that, whether by project or inclination, it suggests a decoupling of authorial ambition and literary psychology. The points of view of Moshfegh’s characters, McGlue especially, don’t speak the received language of poetic mental acuity — they’re in the world. The narrator of “The Weirdos” bears almost silent witness to her boyfriend popping the buttons off his yellow woman’s blazer. McGlue’s stream of consciousness doesn’t mince words (“I am hungry, I think.”). His alcoholism is a farce, and his visions are as coherent as a liar’s dreams. McGlue is just a man; he sees what’s before him, and when he does feel, sets out immediately to make it stop.

Off he goes to the brothel with the rest of the guys. But McGlue reserves a tenderness for memories of Johnson, protector and sweet enabler of his alcoholism. “Simply put, without Johnson I’m just mess pork, sugar, tallow oil, cannel coal and rye.” McGlue’s lawyer encourages him to write his confession, and Moshfegh proceeds with a depiction of male companionship rather sensitive to the idea that the bond between men is, precisely, not homoerotic — unless it is. McGlue longs for the world refined by Johnson’s presence. Nothing is the same without him. McGlue likes girls, even though — in a somewhat broad casting of the fear of the womanly other — they come as a vertiginous blow to his senses. In contrast, the way the guys love each other — easily, fearlessly — is portrayed with beauty and surprise. “‘I’ve got a dream of us on the high water,’ he’d said. He made it happen. He was like that — burning with want and courage, drunk that way. I had so much in kin with him, drunk on drink and supped and with my mouth full of deep meaning, drooling.”

Regarding the smoking crater of adulthood, it remains unclear just how seriously we should take the juvenile. Is it a stunted rut, boyish and dumb to the core? Or is it onto the world, wise to its false promises: patriarchal families, GDP-contributive careers, realism without puke?. For me, McGlue puts two items from recent literary discourse in stark relief: all genres are dissolved by talent, a quantity — whether we like it or not — unevenly distributed (though hopefully not zero-sum; Moshfegh has a lot of it already). But fiction — whether skewed to market or to whim — can be too narrowly contrived; it must take in as much life as it can, no matter the apparent volume of its storytelling. Though it may be that life itself is the greatest of uncertain parodies, McGlue’s world is slight, his perspective necessarily blurry.

The model for McGlue might well have been some salty American classic of arrested masculinity. It’s an awfully impressive stab at it, and it’s also on par with an article in The Toast, say, “Skirts I’ve Been Privy To.” Contemporary novelty gets a strange reception. Clear departures are accused of a kind of tokenism just as often as the status quo is bemoaned or re-invoked. To read McGlue is to be aware of how unmistakably different it is. The term “voice” has too much essentialist baggage — it lowballs the composition involved with sentence-making on Moshfegh’s level. But there’s no other available shorthand for what makes McGlue — literary cul-de-sac, perhaps — a thing of beauty. From where I sit, I still want to be passed a killer note like this one, a doodle of a ship on choppy seas, writing that is what it is with strange aplomb.

M.C. Mah is a critic and novelist with work in The Nervous Breakdown, KGB Lit Mag, and The Rumpus. He lives in Brooklyn.

This post may contain affiliate links.