[New Directions; 2014]

[New Directions; 2014]

The Albertine Workout is written in two parts. The first part is a sequence of fifty-nine paragraphs. The second part is a sequence of fifty-nine appendices. The paragraphs are numbered, have a line of white space between above and below, and are generally short. (Many are a single sentence. The longest is eight.) When you see them on the page they look like layers of stone spanning the paper’s white wall. But when you read them in time they feel like stepping stones, small points of landing under your feet as you run leaping across a body of water.

The reader isn’t the only one running. Albertine, the narrator Marcel’s principal love interest in Proust’s À la recherche des temps perdus, continually evades her admirer: is she a lesbian (all her friends are!)? Is she lying when she says she’s not (her friends kiss in restaurants! Albertine goes dancing with one at the Casino!)? Albertine’s sexuality and bluffing are, according to Carson, two of her best strategies for not being possessed by Marcel. Being a lesbian, lying, and also sleeping. These strategies give her quick feet and keep her free from Marcel, who is running after her in a playground where loneliness is the only weather. They are playing (or Marcel is making her play) a version of tag called “Marcel’s Theory of Desire.” The rule of the game is this: it “equates possession of another person with erasure of the otherness of her mind, while at the same time positing otherness as what makes another person desirable.” If the goal is to tag the other person, what happens when they’re captured? We never find out because, Carson tells us, Albertine runs away. Later, she falls off a horse and dies.

Albertine isn’t the only one running. The volume of . . . temps perdu that features Albertine is called La Prisonnière, or in English, The Captive. Although Carson likes to say Albertine is imprisoned in the narrator’s house, we’ve already noticed that she’s good at evading the narrator’s mind. If the former makes her less desirable to Marcel, the latter makes her more so. It keeps his house of desire at a hot pitch. It keeps him after her. Note that everybody runs in a game of tag. Note that the chaser might think themselves master, but all are beholden to the now-smoking house. Options for escape at this point include crawling out a window and vanishing into the night, seeking horses, diving from the stones and swimming off into the water.

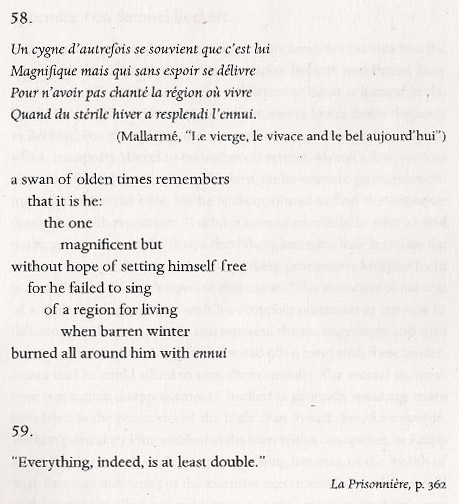

An important part of the Workout is what’s called the transposition theory. The transposition theory proposes that Marcel’s beloved, Albertine, is a fictional stand-in for Proust’s real-life beloved, Alfred Agostinelli (Proust’s chauffeur). Like Albertine, Agostinelli is given lavish gifts by his admirer and dies in an accident. Carson tells us that Proust gave Agostinelli an aeroplane, engraved with a stanza of Mallarmé. She also notes that the yacht Marcel promises to buy Albertine costs exactly the amount the aeroplane did, and would have been engraved with her favorite stanza by Mallarmé. Agostinelli to Albertine is a simple enough exchange, but what’s strange about this case of transposed identities is the name Proust registered Agostinelli under at flying school: Marcel Swann.

That the name of Proust’s manservant sent to spy on Agostinelli was Albert only complicates things further. It makes a certain amount of sense that Albert/ine is Proust’s messenger to his beloved, an elusive message sent to spy on an unknown address. More bizarre is the obsessive, paranoid lover’s decision to write, in one instance, the addressee’s name as his own. What begins as simply double becomes messier and multiple. But back to the poem by Mallarmé. It’s about a migrating swan that gets stuck and left behind, wrapped in the ice of a lake in winter. How cool Carson’s translation feels on the tongue in summer, and how coldly the captive’s predicament rests in the mind. It speaks like a warning, an epitaph, a trail of smoke left by the text as it falls into the ocean:

Marcel isn’t the only one held captive. The Albertine Workout has all the quotidian virtuosity of the ultra-fit. Following the tracks Carson leaves in the language is a little like being a dog for an hour, for a day, walking scented trails at the edge of sense. The appendices are juicy and full of a quiet, delirious energy. So why, like her subjects, does Carson too seem trapped in winter? The intense focus on one man’s jealous, paranoid, and possessive desire, while perhaps instructive, leaves a bitter glare in the eye. Let’s remember the title of the volume in Proust: La Prisonnière, or The Captive. When The Captive transforms into Albertine we expect the birth of a person, but I’m not sure she is ever more than Marcel’s mocking, evasive mirror. This is something, but how much? It’s unclear if the mirror changes Marcel. It’s unclear how the mirror sees itself. Wrapped in silence (unlike Marcel, she is never quoted), Carson’s Albertine speaks most loudly in her escape and death. We don’t know whether this is transformative for her or not, but we do know that Carson associates escape with Roland Barthes (appendix 15b). She says that when he played games, he like to “free all the prisoners, putting both teams back into circulation and starting the game over at zero.” While she notes Barthes’ uneasiness with competition, it is unclear whether the game or its players are transformed in their rebirth, and repetition without transformation is weak medicine, a barren winter burning with ennui.

Perhaps The Workout is a painting I will admire in a Museum, but would never bring home. But let’s be generous. On the other hand, maybe there are times when sustenance need only carve out a small home for itself in unlikely climes, take brief hold and bloom. On the other hand, a certain appendix where one might gather speed over the stones and catch, in the haloed periphery, a glance of exultant, unswimmable water.

This post may contain affiliate links.