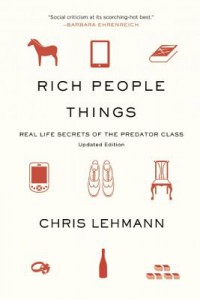

In part a paean to a lost era of the great public intellectual, in part an act of public therapy, Chris Lehmann’s Rich People Things is a savage look at contemporary class privilege and its often unwitting apologists. Rich People Things began as an identically-named weekly column that Lehmann wrote for The Awl; in book form it interrogates those features in our common life that obscure the reality of deep class divisions — some intuitive, such as Ayn Rand and the free market, others less so, such as The New York Times and Malcolm Gladwell.

In part a paean to a lost era of the great public intellectual, in part an act of public therapy, Chris Lehmann’s Rich People Things is a savage look at contemporary class privilege and its often unwitting apologists. Rich People Things began as an identically-named weekly column that Lehmann wrote for The Awl; in book form it interrogates those features in our common life that obscure the reality of deep class divisions — some intuitive, such as Ayn Rand and the free market, others less so, such as The New York Times and Malcolm Gladwell.

Lehmann is a long time editor at Bookforum and contributor to Harper’s, Raritan, and In These Times. He has also worked for mainstream outlets such as Newsday and, until very recently, Yahoo News. I spoke with him about the beleaguered status of social criticism, the ethics of covering the Republican primaries, and writing in the shadows of the 20th century’s leading public intellectuals

In Rich People Things, you hint at an academic background. Can you elaborate on this?

I went to the University of Rochester in the History graduate program and studied with Christopher Lasch. Rochester was a weird place, at least under Lasch, because it was ill-suited to anyone to actually work in the academy. Lasch did history as a kind of social criticism and pitched it to a general readership, and it turns out that this is a poor model for things like getting tenure. In my class, last I heard anyway, only one of the 16 people who came through has a tenure-track PhD position.

Writers who have spent a lot of time in academia often talk about having to unlearn bad writing habits, such as a tendency to use jargon, when writing for a more general audience. Was this the case for you?

I’m unusual, in that going to graduate school made me a better writer. Lasch urged people to write for a general readership and also is a kind of an obsessive person when it came to writing. He promulgated his own style manual that has since been published as a book called Plain Style, which is really good. [In the program] you would hand these seminar papers in and he would give you a typewritten critique that encompassed everything from dangling clauses and modifiers to ideas and it would be almost as long as the paper itself.

Was it this particular approach to historical writing that attracted you to the program in the first place?

Yeah, it was a program that focused a lot on cultural history and intellectual history, which I was interested in. I came to Lasch initially as a reader. When I read The Culture of Narcissism it changed the way I viewed the world, and I wanted to do work like that.

What sort of tradition do you see yourself working in? Are you following in the footsteps of writers like C. Wright Mills, who saw it as their mission to challenge the power structures in America? Or are there others who you find particularly inspiring?

Historians scorn sociology as a rule, but Mills is a good writer. He belongs to a beleaguered tradition, but in a perfect world you’re supposed to have an independent intellectual perch from which to critique cultural institutions, political developments, events.

But Lasch is another obvious figure, along with Barbara Ehrenreich, whose work I have always admired. Murray Kempton is a great old journalist who I edited briefly when I was at Newsday. I think that there is a long tradition within journalism, specifically, of intellectually engaged writing, but for whatever reason the market for journalism has fragmented in a really strange way — from pressures from online sources, as well as profit pressures and the collapse of longer form outlets. At many of my day jobs I’ve been regarded as a bookish freak because I continue to edit Bookforum alongside other responsibilities; I would get a tidal wave of review copies coming in.

In my world I’m living the dream, but — and I don’t say this in any invidious way — some of my colleagues view that as bizarre. “Why would a person be surrounded by books, and not be tweeting?” So, yeah, I hope that I’ve carried on a tradition that goes back to whomever; Murray Kempton, or A.J. Liebling — not that I would ever equate myself to their stature.

You go after a few sacred cows, like The New York Times. Have people reacted strongly to certain chapters in the book?

The Constitution is this revered document, so that is probably the chapter that I got the most flack about. This is another thing that is a legacy of studying with Christopher Lasch — when I first visited Rochester to consider going there, we were talking about his career and he said, “At some point I really discovered that it is a lot of fun to scandalize people.” That has always stayed with me. It’s true.

That is an odd sensibility for a historian.

It is. As I say, Rochester was an outlier, and God bless it. The idea is like the old Formalist mantra of “making the familiar look unfamiliar.” It still mystifies me that people don’t look at Steve Forbes and Alan Greenspan and collapse into laughter. Obviously, they are idols with clay feet.

In Rich People Things, you describe your work as a “roving one-hit methodology.” Can you say more about how you approached the book and the column?

I sort of randomly fell into writing what was designated a column by my editors. They were just trying to continue to get work out of me for no pay. But it so happened that I wrote it in that first flush of trying to sort out the wake of the financial meltdown, so I never lacked for material. I feel like I wrote the column and ultimately the book because I was trying to figure out in my own head what I wasn’t getting from journalism or from book accounts.

There is this sense, and it continues to be a mystery to me, of how we tolerate extreme inequalities, even now with the debate over Mitt Romney’s role at Bain Capital. There is this reverence for people in the paper economy who have destroyed a lot of jobs, and yet they are regarded as creators of wealth. How does that all fit together? What’s the ideology? It is this sort of bastardized Ayn Rand dogma combined with this idea that people who manipulate financial relationships are initiates to some secret doctrine that can’t be criticized. That is just — talking about C. Wright Mills and others — entirely counter to every instinct I have. I wound up criticizing them because other people weren’t.

So it’s one-hit in the sense that I would have to write a column every Sunday. I would have to sit down and open the New York Times’ Business section, Money Magazine, Fortune, or Forbes — which, God knows, is just a treasure trove.

That’s funny, because all those social critics in the ’50s and ’60s used to write for Fortune.

I know, writers like James Agee and Dwight McDonald. That is itself an interesting moment, where you have sort of self-styled anarchists basically running an influential financial monthly. We are living in the detritus of that world. Those kinds of figures are now severely compartmentalized from each other.

Given the kind of mystification that characterizes most of these publications you just mentioned, I wonder if you think there is a responsible way to cover the Republican primaries? It seems like the very grammar of that race is meant to paper over the issues that you write about.

Essentially, until I quit my day job at Yahoo News, that was a big part of my responsibilities. It’s interesting that stuff like Romney’s role at Bain Capital gets shoehorned into story lines like: “did Gingrich’s Super PAC documentary about Romney score any effective points?” There are calls to “truth squad” and “fact check” the video — and those are worthy journalistic endeavors on their own terms — but there is a larger picture being lost here, which is that Mitt Romney is running very deliberately and obsessively on the idea that his experience in the private sector proves he can repair the broken American economy. There isn’t any — at least not that I’ve seen — non-interested (i.e. non-Gingrich) efforts to size up whether Bain Capital, in that sense, created or sacrificed more jobs.

Also, the question that never gets asked is, “What kind of jobs are these?” ”Are they union jobs?” “Are they skill jobs?” Because the coverage is all personality-driven — caught up in the horse race and all other journalistic clichés — you don’t really focus on the intended end-users, which are American workers. And for American workers — to talk about a lost age — unions no longer play a meaningful role in our politics beyond being a revenue stream for the Democratic Party, so no one is held accountable in any meaningful way. Obviously, the Republicans aren’t ever going to give a shit about anything except raising money, but that’s fine, right? There should be someone or some presence out there saying that even if you are creating jobs, how secure are they and what kind of living do they provide?

One issue mentioned in the book, which you’ve just brought up again, is that there are often glaring questions that go unasked by many journalists. How do you explain this particular pathology of the media class?

I mentioned A.J. Liebling before, and I think he’s a very good example. He made a handsome living at The New Yorker, but he was still living hand-to-mouth because of being saddled with a marriage that was a profound drain on his resources. Yet, in his career as a media critic at the New Yorker he would point out things like, “Publishers are bad actors. They destroy newspapers, they destroy jobs.” Now journalism has become professionalized in a way that a figure like Liebling isn’t really possible. Instead of A.J. Liebling, we have David Brooks and others who are on TV and have separate six-figure contracts to be the television personalities who are driving the policy debate. We have a professionalized class that is very different from the sort of journalism that, for my money, does explain longer-term trends beyond the horse race. So I think it’s a class question.

I also think it’s about the fragmentation that I was talking about earlier, where people just feel like they are continually having to feed this digital beast. Often, journalists just register whatever talking points the campaign puts in front of you. For people who are on the trail, it’s a miserable life. You are being fed information from campaigns and you are not really able to get outside of that bubble if you are tracking a candidate. I often wonder, what is the point of campaign journalism? It’s not clear to me.

In a past interview, you described the original “Rich People Things” column as a form of public therapy. Are you still able to practice this, or have you sought out new strategies?

I’ve had to recalibrate in that I don’t do The Awl column anymore. I do a column for In These Times that often addresses the same subjects and, mysteriously, pays pretty well. But I still definitely try in my writing to work through the things that agitate me and make sense of them. That’s what I hope the next book will be.

Speaking of Romney and such things, I had a cover story in Harper’s a few months back which talked about Mormonism and economics, two of my long-standing obsessions. That was therapeutic, in the sense of me finally attempting to understand the way in which Romney’s free market convictions reflect a deeper religious sensibility, which I think is a big missing piece. American capitalism right now is a set of folk beliefs. You have to understand that they don’t come from rational sources. They come from deeply held convictions that we are going to be — as individual congregants or believers — transported into an earthly paradise of wealth, or what increasingly amounts to the same thing. The account of the rapture in Left Behind and other books are very much a continuation of the consumer culture.

Rich People Things is a very funny book, and you even got some nice words from John Hodgman on the back cover. Did humor naturally lend itself to the material, or was it something that you self-consciously tried to work into these pieces?

Especially when you are not getting paid for your writing, you want to have fun doing it. And I do believe in that H.L. Mencken expression, “the politics of the horselaugh.” When you are describing things that are absurd, you laugh to keep from crying, in a certain way. But I think that beyond my subjective pleasure, it’s important reaching a readership, and humor is a good way to do this. Whatever they may teach at the academy, it is not a sin to want to entertain your reader.

Since Rich People Things was first published, we have seen the growth of the Occupy movement. I’m wondering if it gives you hope that some of the broader issues you write about are gaining a critical purchase on the public imagination? Does it also address the problem of political language that you refer to at the end of Rich People Things?

I do think there is much more awareness. It is very encouraging, and I want to see more. The Occupy movement was smart in not formulating an explicit program, as I’ve said in other interviews. Once you issue a list of demands in the dominant media-political discourse you then get pigeonholed as an interest group. Then it becomes a question of “what do the Occupy people want?” And “will they be satisfied by x?” You saw that even in the media headlines of the Obama birther movement — which was insane — but after the White House released Obama’s long form birth certificate, which in evidentiary ways should close all arguments, the media came back and said, “Will this satisfy the birthers?” That’s not the question. Who the fuck cares? These people are crazy. But that is how everything is kept boxed in, in the way our media culture describes our politics. But when the media asks “will interest group x get what it wants?” The Occupy movement says, “We’re not really an interest group, and we don’t necessarily know what we want yet. We’re just drawing attention to a big problem that no one else was talking about.” It’s a good starting point.

Obviously, the challenge going forward is to figure out what they want, and I do think it is a movement that will at some point need leaders. But who knows? In the jargon of past Left movements, you could say that there will be organic intellectuals that will emerge as people build out these problem areas.

How were you able to balance your work at Bookforum with your work at Yahoo News?

Bookforum is a great operation. I feel very fortunate, in the media culture that we have been describing, that I get to edit and assign long form book reviews and essays.

During my day job I would tell myself that Yahoo has the biggest readership of any news source online, and let’s just say that Bookforum doesn’t. I felt in my brain that the two jobs weirdly complimented each other. I could reach this vast readership at Yahoo, and then do more intellectually-engaging stuff at Bookforum, and stay sane.

In Rich People Things you cover a wide range of topics, from more venerable institutions to reality TV. Did you see a logic emerging for the kinds of subjects you wrote about after doing the column and then putting the book together?

The book is different from The Awl column, in that it’s largely new material. I didn’t have a very deliberate sequence of chapters in mind, but I knew that I’d be writing about serious institutions, like the Supreme Court or the Constitution, alongside more frivolous stuff, like reality TV or Steve Forbes. I deliberately kept myself from partitioning these off from each other, because I wanted the tone to be more conversational. Why wouldn’t you talk about the Supreme Court in one chapter and then Malcolm Gladwell in the next? To me, it makes sense. I felt like I wanted the book to be its own thing, but have the feel of the column.

I’m wondering if the topics covered in Rich People Things are discussed most in places like New York and Washington, where many of these institutions are located.

Oh no, it’s certainly not meant to be that. I come from the Midwest, and think of my sensibility as being rooted there, though it is obviously different from someone like Chuck Grassley. But there is a strong progressive tradition in the heartland.

A good friend of mine, Catherine Tumber, just wrote a great book about small cities and economic revival strategies involving green technologies. There are large swaths of this country that have been consigned to the dustbin and have been trying to recover. They know that the paper economy has done them no favors and they have to create different kinds of economic solutions and institutions that are more responsive. Those are the conversations that are interesting to me and will bubble up, much like the Occupy movement, into something — I don’t know what.

Was American populism the topic of your unwritten dissertation?

I’ve always been interested in populism, but my dissertation was going to be on religion and the professional innovation of evangelism in the 20th century — which, weirdly, I think is what my next book will take up, in part.

Our core beliefs about economic life are not rational; I believe they have religious content that demands some scrutiny. The history of reform in the early American republic is a history of revivalism. You can argue that the civil rights movement, too, lies in the revivalism of the black church. It’s very interesting that revivalism has gone completely — well, not completely, because it’s obviously involved in the conservative wing of the culture wars — but the tradition of Protestant reform is largely dead. To me, it’s an interesting story — how that has happened and why. Even though there are religious features to the way we think about economic life, there is no sense that these realms should have anything to do with each other.

You’re in a band called The Charm Offensive. Is this another side of your work as a social critic?

I was very much influenced by punk rock and politically-minded bands like the Minutemen. My lead guitarist used to be in Ian MacKaye’s first band, Teen Idol. I like Fugazi, but I’m not of the D.C. hardcore scene, by any means. My stuff is more poppy.

It is the only coherent ambition I ever formed in my young adulthood that has stayed with me. Though becoming a rock star never panned out, I keep going at it. But I write a lot of break-up songs, so it’s not economic.

This post may contain affiliate links.