As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals & Notebooks, 1964-1980

Susan Sontag; ed. David Rieff

Farrar, Strauss and Giroux (April 10, 2012)

I.

“Why do we read a writer’s journal?” Susan Sontag wrote in 1962.

Because it illuminates his books? Often it does not. More likely, simply because of the rawness of the journal form, even when it is written with an eye to future publication. Here we read the writer in the first person; we encounter the ego behind the masks of ego in an author’s works.

This account is half true in the case of Susan Sontag herself. The publication of the second of three volumes of her journals, As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals & Notebooks, 1964-1980, offers the tantalizing prospect of apprehending Sontag in the first person. It is no small draw, though, that the Sontag of 1964 to 1980 produced the work she is most famous for: Against Interpretation, with its riveting title essay and “Notes on ‘Camp’”; “Trip to Hanoi,” written at the height of the Vietnam War; On Photography; and “Fascinating Fascism,” her polemic against Leni Riefenstahl and fascist aesthetics.

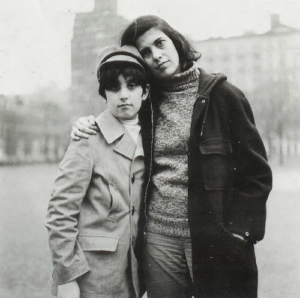

So we do look to these journals to illuminate her books—but in some sense her books are indivisible from the “ego behind the masks of ego.” The allure of those gut-wrenching, brilliant essays is coextensive with the allure of their magnetic, brilliant author. Ideally the journals would reveal something about both. The voice of utter authority in the work has its corollary in the tall, self-possessed figure; the tone of unapologetic seriousness finds expression in her famously forbidding demeanor. Reviewers can’t resist referring to her as a “high priestess” or a “princess,” usually of American letters. In photographs all her features seem outlined in charcoal, her eyes and hair startlingly black. The persona, manifested in her writing and in her life, beguiles: Susan Sontag the prodigy, Europhile, sometimes-lefty, who could write about anything, take lovers from both sexes, and drop every notable name of her day. The journal promises the person behind that persona.

The private Sontag it reveals certainly shares some core traits with the public Sontag. Chief among these traits are avidity and seriousness. She made frequent, admiring use of these words, which also name her most defining characteristics. Her essays overwhelm the reader with her encyclopedic command of literature, art, theory, philosophy; her interest in culture high and low. It’s a bit like reading Milton, if Milton had been a film buff. All those names! All those titles! The journals confirm her voraciousness; in them she describes the need to read as an “awful raging hunger.” She draws up booklists of incredible length and variety—and not those aspirational lists in the Emma Woodhouse tradition, about which Mr. Knightley can only comment that they are “very well chosen, and very neatly arranged.” Sontag’s day-to-day reports of what she actually read (and, dizzyingly often, reread) are staggering. Her list of the best films peters out at 228.

Her seriousness is similarly forceful. She is entirely serious about being serious; she uses the word liberally in her essays (usually to designate “serious art”), free from embarrassment at appearing elitist or humorless. Sometimes it’s hard to believe this is the woman who taught the world about Camp. The potential Camp in her own sensibility seems lost on her. She records notes on Brecht and definitions of lewd slang and with equal fastidiousness: “’Bumtrinkets’—bits of feces stuck to hairs of anus (cf. Cicely Bumtrinket in Dekker’s Shoemaker’s Holiday).”

These similarities between the public and the private figures aside, what we discover in her notebooks is, if not the person behind  the persona, at least a very different persona. The most striking difference is one of tone: the timbre of authority that rings through her criticism—that makes Sontag Sontag—is largely absent from the journals. Here we see her insecure, unhappy in love, fretting over her sexual abilities, admonishing herself to smile less, obsess more, read less, write more. The journals span many love affairs, which vary widely in their prevalence on the page. The women in her life occupied her more than the men. She writes about Jasper Johns frequently as an artist, sometimes as a friend, and in a single, glancing remark as her lover: “Jasper is good for me. (But only for a while.)” The women she loved, though, undid her. In a typical reminder to preserve herself in her affairs, she writes, “What I have to get over: the idea that the value of love rises as the self dwindles.” Her descriptions of these affairs paint her as practically retiring—and no doubt she behaved very differently with her lovers and loved ones than in public, as most of us do. Of the Duchess Carlotta del Pezzo, the lover who occasions the most distress (or at least the most-documented distress) in Consciousness, she writes, “Remember what she said the other day about finding me so different from the way I appeared at first (autonomous, ‘cool’)?” Sontag then urges herself to maintain the façade of cool autonomy that inevitably crumbled in her relationships.

the persona, at least a very different persona. The most striking difference is one of tone: the timbre of authority that rings through her criticism—that makes Sontag Sontag—is largely absent from the journals. Here we see her insecure, unhappy in love, fretting over her sexual abilities, admonishing herself to smile less, obsess more, read less, write more. The journals span many love affairs, which vary widely in their prevalence on the page. The women in her life occupied her more than the men. She writes about Jasper Johns frequently as an artist, sometimes as a friend, and in a single, glancing remark as her lover: “Jasper is good for me. (But only for a while.)” The women she loved, though, undid her. In a typical reminder to preserve herself in her affairs, she writes, “What I have to get over: the idea that the value of love rises as the self dwindles.” Her descriptions of these affairs paint her as practically retiring—and no doubt she behaved very differently with her lovers and loved ones than in public, as most of us do. Of the Duchess Carlotta del Pezzo, the lover who occasions the most distress (or at least the most-documented distress) in Consciousness, she writes, “Remember what she said the other day about finding me so different from the way I appeared at first (autonomous, ‘cool’)?” Sontag then urges herself to maintain the façade of cool autonomy that inevitably crumbled in her relationships.

Sometimes it’s hard to remember, having pierced that façade, that she’s Sontag, the high priestess. In her insecurity we see the sharpest divergence between her public and private selves, between the work and the author. She offers one account of this discrepancy: “I am so very much more cool, loose, adventurous in work than in love,” she says in 1970. “So much more inventive.” Later, in the aphoristic form she often used in her notebooks, she writes,

In ‘life,’ I don’t want to be reduced to my work. In ‘work,’ I don’t want to be reduced to my life.

my work is too austere

my life is a brutal anecdote

The confidence she brought to her work remained confined to her work. And, in accordance with her observation on writers’ journals, her notebooks don’t particularly illuminate her books. Though the work seeps into Consciousness far more than it did in the first volume of her journals, released in 2008, it’s not that satisfying to see the runty infancy of ideas that later become mature essays. She quotes her friend, the theater director Jonathan Miller, as saying, “I take [Lionel Trilling’s] ideas less seriously since I know him.” This is one peril of the journals: confronted with the quotidian reality of Sontag, it’s easy to forget the power of her ideas and critical voice.

Oddly enough, she cringed at the power of this voice. She periodically resolved to quit writing essays, objecting, “I seem to be the bearer of certainties that I don’t possess—am not near to possessing.” She paints an almost convincing portrait of herself as dithering, weak-willed, lazy. But then she nonchalantly reports something like this: “After 25 hours of work (dexamyl…),” the upper that sustained her writing for years, “I think I’ve sorted things out.” Ah, yes. All diarists draw distorted self-portraits: they measure themselves against internal standards they have no reason to explain. Given the unforgiving standards Sontag used, she makes an especially unreliable narrator.

Some of these dynamics will be familiar to those who read the first volume of her journals, Reborn: Journals and Notebooks, 1947-1963, which covers Sontag from ages fourteen to thirty. The aphoristic, note-taking form; the omnivorous observations; the catalogs of books, movies, words; the self-castigation; and the heartbreak appear equally in both volumes. Consciousness contains more conventional diary entries than Reborn, however. Though she rarely recounts—there’s no story in these journals, and even her daily life is obscure—she practices more self-excavation here than she did in young adulthood. She turns that incisive critical eye on herself, marshalling evidence from her behavior, weaving theories about her character. The reflective project rises to a crescendo in several long passages from 1967—the saddest and most beautiful of the journals—analyzing her childhood, psyche, and relationships with her mother and her then-lover. “Case-history stuff,” she calls it.

These entries have more in common with her essays than her intellectual jottings do. They are essays on herself. They mark a departure from the fragmentary, impressionistic form of much of the notebooks. Here she wields “hence,” “then,” “in radical contrast to,” “from which I can infer.” She chronicles the alienation of being a brilliant child—and more than that, of being an avid and serious child. “I would try to scale myself down to size, so that I could be apprehended by (lovable by) them,” she writes of her family. She tried not to “overload their capacities, frighten them, make them feel stupid, alienate them, make them hate me for making them feel stupid.” She felt intense frustration with people less avid and serious than she was—most people, that is, hence her reputation for being frosty. She thought these “incredibly obtuse and stupid people…couldn’t be that stupid if they wouldn’t be so lazy or distracted or undermotivated. They could be intelligent, they could see, if they tried. But nobody wanted to try.” When she writes of her mother stashing Redbook when teenage Susan came to kiss her goodnight, it’s hard to know who to pity more: poor Mildred, flinching at the judgment of her donnish daughter, or the daughter, pining for an intellectual and spiritual peer.

II.

While I had hoped, against Sontag’s advice, that her journals would illuminate her books and herself, instead I found myself consulting her work to illuminate her journals. Or rather, I began to triangulate between the work, the journals, and the person. Sontag wrote little that qualifies as memoir. Her son David Rieff, who edited her journals, says in the introduction to Reborn that her essays on Elias Canetti and Walter Benjamin were “as close to a sally into autobiography as she would ever make.” As her essays on other writers provide insight into her life, her essays on writers’ journals provide insight into her own journals.

And there can be no doubt that Susan Sontag was composing a writer’s journal. In both volumes she assiduously constructs (and deconstructs) her identity as an artist. While she is remembered for her criticism, she considered herself a novelist first, and  resented her middling artistic success. In a 1980 journal entry she writes of Barthes, “People called him a critic, for want of a better label; and I myself said he was ‘the greatest critic to have emerged anywhere…’ But he deserves the more glorious name of writer.” For Sontag, “writer” would always be the more glorious name. Surely she extends this charity to Barthes with her own better labeling in mind. Another essay on Camus’ Notebooks sheds light on her private writings: “The notebooks of a writer have a very special function: in them he builds up, piece by piece, the identity of a writer to himself.” The elements she describes as being important in a writer’s diary (the will, solitude) are indeed strong currents in her own. For Sontag, building up the identity of a writer meant exhorting herself to develop what she viewed as the proper writer’s temperament. “My character, my sensibility is ultimately too conventional,” she wrote. “…I’m not mad enough, not obsessed enough.”

resented her middling artistic success. In a 1980 journal entry she writes of Barthes, “People called him a critic, for want of a better label; and I myself said he was ‘the greatest critic to have emerged anywhere…’ But he deserves the more glorious name of writer.” For Sontag, “writer” would always be the more glorious name. Surely she extends this charity to Barthes with her own better labeling in mind. Another essay on Camus’ Notebooks sheds light on her private writings: “The notebooks of a writer have a very special function: in them he builds up, piece by piece, the identity of a writer to himself.” The elements she describes as being important in a writer’s diary (the will, solitude) are indeed strong currents in her own. For Sontag, building up the identity of a writer meant exhorting herself to develop what she viewed as the proper writer’s temperament. “My character, my sensibility is ultimately too conventional,” she wrote. “…I’m not mad enough, not obsessed enough.”

No diarist writes free of self-consciousness. Still, one can’t help but wonder of someone so well versed in writers’ journals how much she fashioned her own notebooks as exemplars of the genre. At one point she coyly wonders if it is “possible that someday someone I love who loves me will read my journals—+ feel even closer to me?” Given her ambitions, she must have hoped they might one day reach a wider audience. Reading them, we are always looking at Sontag looking at us looking at her.

Consider Sontag’s remarks about why we read writers’ journals quoted at the beginning of this piece. They appeared in her essay “The Artist as Exemplary Sufferer,” from Against Interpretation, her first work of criticism. The journal in question belonged to the celebrated Italian writer Cesare Pavese. Pavese was an exemplary sufferer indeed; obsessed with his sexual inadequacy and emotional frigidity, he eventually killed himself. According to Sontag, we desire “the writer in first person” not because we are interested in writers per se, or even in particular writers, but because we are interested in suffering. The appeal of writers’ journals comes from

the insatiable modern preoccupation with psychology, the latest and most powerful legacy of the Christian tradition of introspection… which equates the discovery of the self with the discovery of the suffering self. For the modern consciousness, the artist (replacing the saint) is the exemplary sufferer. And among artists, the writer, the man of words, is the person to whom we look to be able best to express his suffering.

Might Sontag have cultivated her suffering to prove her writerliness—to herself or to us, her imagined future readers? In Reborn, she wrote, “In the journal I do not just express myself more openly than I could do to any person. I create myself.” Perhaps the self she created there was a suffering self: the sufferer as exemplary artist. If she lacked the wherewithal to be mad, obsessed, at least she could suffer. Thus the gap between the public Sontag (confident, commanding intellectual) and private Sontag (unhappy, insecure mortal) is not so hard to bridge. Each persona—for they are equally personas—is an expression of Sontag the writer.

Of course, as Rieff points out in his introduction to Consciousness, diaries are prone to selection bias. Even if their purpose is not primarily therapeutic, they likely contain an unrepresentative sample of pain. The journals give “a false impression of my mother’s life in that she tended to write more when she was unhappy, most when she was bitterly unhappy, and least when she was all right,” Rieff writes. But he acknowledges that happiness “was not a well from which my mother ever was able to drink deeply.” Perhaps the oddest feature of the suffering registered in Consciousness is that it is almost exclusively romantic, even though Sontag underwent a punishing regimen of chemotherapy for stage four breast cancer from 1975 to 1977—a calamity she scarcely mentions. Is this silence sangfroid? Terror? The conviction of her own immortality that Rieff ascribes to her?

Whatever the explanation, “The Artist as Exemplary Sufferer” offers romantic suffering as the highest suffering. “The cult of love in the West is an aspect of the cult of suffering—suffering as the supreme token of seriousness (the paradigm of the Cross),” she writes. If ever anyone drank the Kool-Aid of seriousness, of course, it was Sontag. She believed her suffering in love—her passion, say—proved that seriousness, and thus confirmed her artistic worth. “It is the author naked which the modern audience demands,” she says, “as ages of religious faith demanded a human sacrifice.” Just because she disavowed this demand does not mean she didn’t succumb to it. The journals show Sontag as naked as such a shrewd and well-read writer can be. But how naked is that, exactly—how naked is calculated nudity? We are left to wonder whether Sontag, consciously or not, volunteered herself as the human sacrifice she believed the audience demands.

III.

Another unreliable narrator lurking in Consciousness requires mention. Behind the various personas of Susan Sontag stands her son, the sole executor of these journals. In his reluctant introduction to Reborn he wrote that Sontag left no instructions for the fate of her notebooks. She sold her papers to the UCLA library, though, and Rieff says he decided to publish these volumes under the reasonable assumption that if he refused the mantle someone else would take it up. As in Reborn, he provides scant biographical information or relevant annotation, and no explanation of gaps, omissions, dated entries transposed, the form and physiognomy of the books themselves, or his own process of deciding what to keep and what to cut. Consciousness abounds with vexing ellipses: I assume they are Rieff’s, not Sontag’s, but he never clarifies, and they always seem to interrupt at the wrong time.

In the preface to Consciousness he reiterates his assertion, made in the preface to the first volume, that he has not attempted to protect Sontag’s image or spare anyone’s feelings, including his own. At the very least, however, he seems not to understand what is of interest to those for whom Sontag is of interest. His notes include too much of that hateful phrase, “a representative sample.” (He prints only the first 50 of those 228 best films.) At one point, he inserts: “[In passing, SS notes:]….” What is “in passing”? Elsewhere he notes where parts of the text were written in the margins, but here he does not—how does “in passing” present itself on the page? What did those books (nearly a hundred of them) look like, feel like? I longed to see an entry in Sontag’s hand. She would certainly have disapproved of this inattention to form.

In the preface to Consciousness he reiterates his assertion, made in the preface to the first volume, that he has not attempted to protect Sontag’s image or spare anyone’s feelings, including his own. At the very least, however, he seems not to understand what is of interest to those for whom Sontag is of interest. His notes include too much of that hateful phrase, “a representative sample.” (He prints only the first 50 of those 228 best films.) At one point, he inserts: “[In passing, SS notes:]….” What is “in passing”? Elsewhere he notes where parts of the text were written in the margins, but here he does not—how does “in passing” present itself on the page? What did those books (nearly a hundred of them) look like, feel like? I longed to see an entry in Sontag’s hand. She would certainly have disapproved of this inattention to form.

Knowing Rieff edited Consciousness lends special discomfort to the already uneasy experience of reading private journals: we are also always looking at Rieff looking at Sontag, and looking at him looking at us looking at her. The most jarring moment comes in 1965, when she writes, “One thing I know: If I hadn’t had David, I would have killed myself last year.” It’s impossible not to read this line through his eyes.

While he certainly allowed the inclusion of passages that must have pained him to read, we don’t know how much he cut her down to size. So Sontag is mediated through her son as well as through herself. Between the two we may get the writer in first person (first person plural); I doubt whether we get the writer naked. But that’s no reason to disdain Consciousness. Sontag cloaked is well worth the read.

Rachel Luban lives in Chicago, where she reads, writes, and makes coffee.

This post may contain affiliate links.