[7.13 Books; 2020]

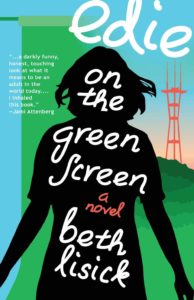

A late-90s Bay Area It Girl (or gender-neutral “It Pal”) finds herself in 2011 an “aging townie.” In Edie on the Green Screen, Beth Lisick’s first novel, the details dribble from a series of reminiscenses structured like a sitcom flashback episode. The regulars at the Mission District bar where the California native worked for 20 years still call her Edie Wunderlich, and most just assume she was in a band. No, Edie never made it as a rocker or gallery artist, but she was on the scene. Without scenesters like her, the scene would never have existed.

Suddenly, with the news of her mother’s death, Edie finds herself taking account of what, if anything, she has to show for her free-spirited life. In what ways has she been let down, left behind or complicit in her own stunted development? Reconnecting with her jet-setting brother, Scott, looking for a new job and rehashing old flames, Edie wonders if she even really wants to embark on the personal American project known in contemporary speak as “adulting.”

In these meandering chapters, Edie bristles at the unwelcome changes that have taken over her beloved, hip city. Lisick populates these streets and alleyways, from then and “now,” with believable punk characters in sharply drawn costumes and poses. Normal people like her brother Scott are a drag. But Edie has painted herself into a precarious corner by resisting the web, and thus isolating herself from not only the mainstream but the counter-culture such as it is. As she explains to the readers: “Hating the internet was a semi-popular claim made among people who used it regularly, but few Americans, besides the elderly, impoverished, and incarcerated, had as little experience with it as I.” As a rebellious off-the-gridder, Edie shows conviction where so many among her tribe have simply acquiesced.

This new novel isn’t Lisick’s first attempt at problematizing the bohemian, or the fall of San Francisco from bohemian idyll to pricy tech-bro playground. Her collection of humorous personal essays, Everybody into the Pool (from 2005), wraps around the same cultural pivot. A standout essay in that book, “Alternative Cyber-Column,” tells of the experience and ennui Lisick gained from being an alt-weekly nightlife columnist. (I take this experience as a main source for the new novel.) This being in the early days of the web, Lisick writes for the site owned by an area publisher and feels cordoned off in a virtual space of emails, obscurity, and exaggerated minutiae that spurs her flight from freaky dive bar acts like the Poke n’ Grope to a wholesome community theater production of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. Though her cyber world press credentials fail to get her on a guest list in the real world, she’s fed arcane gossip by publicists and friends, and recoils. Chelsea Clinton eating at a restaurant, or Robin Williams performing an impromptu set, will get a voicemail from The National Enquirer. When she runs a blind item about a band who isn’t getting booked because they are “annoying,” nothing more, the hatemail streams in.

Without having to connect too many dots, reading Lisick’s books today suggests that, as all politics are local, the global web hysteria that destroyed American politics as we know it also began locally. Just in the way that Wynona Judd’s new rescue dog (again, back in the ‘90s) has no place in a San Francisco alt-weekly, irrelevant national and corporate motives warp any individual’s perspective on what should matter in a sane, balanced community. (Even if sane, balanced communities don’t exist, we at least form our judgements according to what we think would make sense in a world that made sense.) What’s unnerving is how the same basic problems about the digital takeover arise at all times in this now historically slow creep across three decades. It seems not to matter if Lisick is writing in the early aughts about the old century, or if she’s writing today about the beginning of the decade just concluded. Authentic human connections are curtailed by digital distractions; people are wrenched out of their physical place when summoned by mobile devices. As Edie’s, or Lisick’s, grievances give voice to the stubborn resistance of many laggards against fully integrating technology into their lives, they also suggest that most of the web’s paltry offerings to date don’t seem all that appealing. As Edie’s life spirals out of control in the middle act of Edie on the Green Screen, her authority wanes. Lisick keeps things interesting by refusing to draw a clear line as to whether this is a heroic tale about resistance, or a tragic warning to fellow dropouts.

Because the novel’s heroine is largely unreliable, Edie on the Green Screen can’t directly challenge the digital turd bombs we deal with in everyday life — fake news, the gig economy, hatred and the preemptive fear of hatred. Although the title’s jargony “green screen” analogy hints at a theory-informed systems novel, this one is decidedly personal and non-encyclopedic. Sure, Edie’s desultory, cantankerous riffs sometimes land on the mainstream’s digital overdependence. But the rush of midlife angst spewing through the narration comes from a crack in Edie’s life — the death of her mother. This event forces Edie to come to terms with what she’s been doing all these years working behind a bar, squatting with friends in a leaky warehouse, puzzling through her own self-described “complete lack of ambition.” The way confusion sets in around this life event is realistic and sympathetic mainly because no clear connections can be made between the decisions Edie made in her twenties and the unmanageable life she struggles through in the present.

Putting her mother’s San Jose residence on the market, Edie meets the ghosts of her suburban origins. If Edie is a relic of the waning San Francisco punk scene, she’s also a Rip Van Winkle of the burbs. Childhood neighbors might be graying, and their lawns turning brown, but a new generation of Silicon Valley settlers are waiting to pounce, and price out the marginalized underclass. At the same time, Edie comes to grips with an original sin ingrained in the suburbs, and her perhaps quixotic pursuit of the authentic diversity of those who’d taken refuge in the city. “If I was confident in who I was, if I was such a solid person, why did this overplayed rejection of my past have such a tight grip on me?” Edie wonders. “The word suburbs, which in the beginning was purely geographical, had come to connote so much more. Wealth, comfort, safety, whiteness.”

There is some overlap here with the real-life essays by Beth Lisick, who James Frey once called “a wolf in girl-next-door’s clothing.” As a voice of her generation, Lisick’s writing chops — her fangs — make her a wolf, even though she wears the trappings of a suburban sensibility. Through Edie, Lisick illustrates a deeper paradox as an outsider who mixes with but doesn’t feel a part of the other outsiders. In her introduction to Everybody into the Pool, Lisick (as herself) blames her “normal” childhood. “I loved my normal upbringing,” she writes. “I just think the fact that I had a stable childhood was precisely what let me stray pretty far away from it without ever landing in therapy, rehab, or jail or having an identity crisis, eating disorder, drug problem, or prescription for antidepressants.” If you’re “too normal for the fringe world,” you wind up in limbo until an event from outside shakes you.

Edie inserts herself into this milieu while looking after her mother’s house. Young mechanics help jumpstart her mom’s station wagon, and her friend Lydia’s nephew, Trinket (real name: Brandon), guides the old-school fortysomethings through a more depraved and corporatized club scene, the graffiti scrawled on buildings now all feel-good slogans (“Be Gentle With Yourself”) sponsored by a mobile app. She’s horrified that some of her old friends have kids now, and that these precocious pre-teens have formed their own punk rock band, playing daytime sets in the same old bars when their peers are kicking soccer balls around. When Edie reluctantly goes to her hometown public library to print up a resume, or when, following a chance encounter at an arcade, she goes job shadowing at a Silicon Valley startup, Edie’s ambivalence proves how much of an outsider she is next to the adherents that have truly bought in.

In each encounter, Lisick showcases her talent for blending the history of an earlier time with the present action, punched with observational wit in condensed sketches, as when Edie passes by the Sklamberg residence on her way to the library:

Poor Mrs. Sklamberg. She had gotten divorced sometime in the mid-’70s after her husband took off for Grass Valley with the lady who sold vitamins at The Nut Hut, the sad old health food store in the nearby strip mall…When Mr. Sklamberg, a pilot for Pan Am, moved out with Nut Hut Donna, Mrs. Sklamberg raised five kids by herself, getting heavier and more outwardly Fundamentalist every year until finally, the last kid, the checker at Albertsons, left the house and she kind of fell apart. She even stopped going to her megachurch, the one that had the wooden Jesus, whittled real skinny, on the corner of Moorpark and Mitty. Scott and I once threw frozen peas at Him from the way back machine of the station wagon, shouting, “Crucify Him! Crucify Him!” and laughing our brains out.

After another boozy night in the city with another friend, Deirdre, Edie searches for her mom’s lost station wagon and ponders all the lost stories that will never be told, those left haunting San Francisco’s alleyways between “cheaply built modern condos and waterlogged Victorians.” Edie speculates, “Maybe once the mapping vehicles with the cameras on top were finished photographing every square-inch of the earth, they’ll be free to circle back and vacuum all the stories.”

Reading Lisick, one gets the sense that Edie Wanderlich herself is a kind of stand-in for the old Internet, her bartender’s proficiency at injecting trivia and gossip into increasingly mundane situations abandoned by a mobile-first generation’s lack of curiosity. There is, of course, an app for that: the novel.

Christopher Wood lives in New York. His poetry, fiction and essays have appeared in The Millions, Dispatches from the Poetry Wars, Vol 1 Brooklyn and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.