[Dedalus Africa; 2019]

Tr. from the Portuguese by Jethro Soutar

What is the meaning of freedom? Could it be:

She would venture out into the world and find a place where there were no memories to contend with, no screams to suppress, no people to avoid; a place where everything was new and nothing and nobody made her think of her past or her future. Now that was freedom.

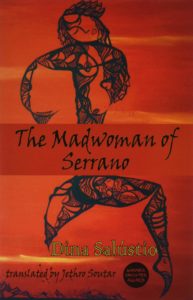

What does it mean to define freedom through absence? What does it mean to believe freedom is the absence of trauma? Can such freedom ever be achieved? In Dina Salústio’s The Madwoman of Serrano, first published in Portuguese as A Louca de Serrano in 1998, now translated for the first time into English by Jethro Soutar in 2019, characters converge through magical and realist elements to explore how environment, cultural identity, and language might make freedom simultaneously possible and impossible.

The Madwoman of Serrano offers archetypal, even familiar, character and plot elements: a man struggles to find his place in the world, a girl must leave home to find her way into adulthood, characters find love in unexpected places, men and women both feel confined within a tradition-centered community, environmental crises threaten a village and its practices, the allure of the city conflicts with nostalgia for the simplicity of rural life, and more. However, Salústio offers anything but a straightforward narrative. Instead, she weaves and fractures details to generate a space where characters exist “in that imprecise hour that’s no longer today but isn’t yet tomorrow,” a liminal place realistic and yet surreal “halfway between sleep and consciousness,” where readers, like characters, are “stuck between two worlds.”

The novel opens in the rural village of Serrano, “a solid place” and also a slippery place “half beautiful, half woman, half man.” First named when the village’s inhabitants are pressured by visiting governmental agents interested in the village’s natural resources (a point of conflict later in the novel), Serrano offers a predictable agriculture- and tradition-based cycle of rural life. Here, characters work to maintain “the preservation of a deep peace” within which “the mountain range that enclosed their village, river, and inlet shut them off from the rest of the world, and would do so for as long as they could keep it that way.” However, lest this feel too familiar, Salústio enhances this expected rural narrative with original details.

Thus, Serrano is also a place where the only observed public holidays are the additional funeral rites for individuals who committed suicide, where women never give birth less than four years after marriage, and where cats with venomous claws are cherished. Sometimes, Salústio juxtaposes the familiar and magical in the same page, even paragraph, as when, with the cats:

. . . there were very few cats in the valley, though the existing ones were much loved, especially by the men. Not to eat, just to have around the house. Indeed the villagers loved their cats so much that . . . they resolved to build them a special home. Erected at the entrance to the valley, and considered quite a curiosity, the cat hut had five evenly-distributed alcoves where cats could sleep, when authorised to do so by their owners, those villagers who’d adopted them as pets or as guard cats. Yes, guard cats: everyone knew what damage a Serrano cat could do with its venomous claws.

While you or I might not have guard cats with venomous claws, Salústio offers Serrano as an allegory for the communities of her readers, stating that “the story of the village . . . was the story of all the Serranos of the world, places cursed and held back by foolishness.” In Serrano, while villagers work to preserve “deep peace,” this obsession with maintaining peace and order leads the men to murder a woman and harm other women who voice the men’s “fear” and “their inability to put their heads together and discover new truths, their attachment to impossible dreams, their willingness to settle for scraps.” Salústio jars readers by setting scenes where readers sympathize with characters, as when a man neglects his work to care for an ill woman, next to scenes that jolt readers out of sympathy and into surprise, even horror, as when men murder a woman for speaking out. Serrano is our village, too. Perhaps we all have experienced moments when we chose silence when we should have chosen voice. In this political moment, when the rights of women and non-white individuals are questioned and rescinded, this novel’s reminder of the dangers of silence, and how an accumulation of silences can inhibit, even prevent, freedom, feels apt.

Serrano is a largely patriarchal community, where “the female is the soil” and older women must often comfort the many “young women whose lives had become unbearable from beatings and betrayals, threats and humiliations, sex being withheld or violently forced.” Even so, Serrano is guided by two major female figures: its madwoman, a younger woman able to predict the future, interpret omens, and reveal these often contentious statements in relative safety, and its midwife, a woman who provides every medication, oversees every birth, and sexually initiates every young man in the village, all of which occur in her “House of Light.” Interestingly, both the madwoman and midwife are “born anew” in different bodies in different cycles. The madwoman lives from age 9 to 33, then disappears to be reborn in a new girl who arrives without explanation in Serrano; and the midwife is chosen at the age of 33 after the death of her predecessor from an existing community member who, after drinking a potion in the House of Light, “forgot her name, lost her memory, and became ageless.”

The novel opens with the current midwife “at the centre of the scene” and, arguably, the narrator of the story, for, in the first sentence, readers learn,

This is the story of Serrano, a village of one hundred and ninety-three souls, including a young madwoman, several infants and three babies on the way, two of them twin girls, according to the midwife . . .

Yet, this novel is The Madwoman of Serrano, not The Midwife of Serrano, a translation choice aligned with the original Portuguese title A Louca de Serrano. Why does Salústio highlight the madwoman in her title, not the midwife or even both women, even though both are featured throughout the text, with the midwife arguably more so? Later in the novel, the madwoman tells a central female character the midwife “can’t see into our eyes and souls.” This opacity, generated by the midwife’s absence at both women’s births, threatens her otherwise encompassing power. Sometimes, perhaps, silence is power, and the novel follows one character through years of muteness and her eventual exile from Serrano because of this. How might silence generate freedom? How might silence be another form of speaking? (How might inaction be another form of action?) And how might language shape our identity, agency, and freedom?

In 1998, this book became the first novel published in Cape Verde by a female author. Now, in 2019, Salústio’s novel has become the first such work translated into English. Soutar, general editor of Dedalus Africa, completed this translation through support from English PEN’s “PEN Translates” program to promote diverse literatures and authors’ freedoms, as well as Dedalus’s “Celebrating Women’s Literature: 2018-2028” initiative to publish six new books (mostly translations) each year from female writers for this ten-year period, in commemoration of UK women gaining the right to vote in 1918. As a translation, then, this novel adds another level to its interrogation of the role of language on silence, identity, agency, impact, and freedom.

As a translator, I often wonder how visible to make the translated nature of the work to readers. Do I Anglicize names of people or places, or do I retain original names? With historical work, do I try to adopt a writing style contemporary to the original or contemporary to our current moment? Do I retain any repeated or short phrases in the original language? With several major publishers downplaying a work’s existence as a translation, often withholding the translator’s name from the cover, even the title page, Dedalus makes a bold statement in choosing, instead, to include Soutar’s name on the front cover, information about the translation on the back cover, and an “About the Translator” following the “About the Author” in the front matter. This novel is a translation, and knowing this from the front cover may help readers to engage with this novel with fewer preconceptions, allowing the juxtaposition of Salústio’s elements and of Soutar’s register and tone to generate more friction.

Soutar makes bold choices in his translation style, often forcing the reader to re-realize the novel’s identity as a translation through his use of divergent registers and jumps in tone. Particularly in the first half of the novel, these divergences and jumps feel conspicuous, and could be interpreted as a translator trying on different voices to see which will be the best fit for the final work. For example, Soutar gives the formal and Victorian phrase, “the madding stars,” in the same paragraph as the colloquial, “avoid becoming its slave, which he already was anyway, he just didn’t know it yet.” A few pages later, he shifts from conversational to colloquial to formal in one sentence with, “The officials took a step back, or a hop back, for they were still all standing on one leg, fearful that the transformation of the hillbillies-become-highlanders would continue and that a previously timid and helpless people might turn violent.” These jumps took my attention from the narrative and into stylistic questions, and I often wondered how Salústio navigates registers in her original text.

It is quite possible, as critic Ann Morgan wrote, Soutar’s clash of registers mirrors Salústio’s impressive range, for the novel itself jumps from rural Serrano to an unnamed city, or between perspectives, or across decades, between and within chapters. If that were so, though, I would expect to see this friction of register and tone across the span of the novel, but I found the frequency highest in the first third and almost nonexistent in the final third, even though the Salústio’s narrative remains fractured and wide-ranging through the final pages.

I am fascinated by word choice in translation. Connotation is so multivalent in one language, and to translate across languages accentuates this complexity. Given this novel’s status as the first by a female author published in Cape Verde, the first such to be published in English, and a featured novel in Dedalus’s “Celebrating Women’s Literature” initiative, as well as an extended exploration of female agency and freedom, I found myself curious both about the decision to have this novel translated by a man, and about the words used to describe women throughout (including “floozy” and “hussy,” “witches,” “bitch,” and “imbecile” and “wench”). I am curious how these translated terms compare to their Portuguese originals, but, even as I ask this, I wonder how my reading of these terms is complicated by my identity as an American millennial and gay man. Perhaps, by causing this friction alongside the novel’s other frictions in setting, plot, and character, Salústio and Soutar work to provoke readers to question their reading lenses, their preconceptions, and their privileges.

Salústio’s The Madwoman of Serrano is a complex, even puzzling read. While a number of plot-driven questions resolve toward the novel’s end, the questions of female agency and freedom linger in my mind. In a novel where speech and silence are linked to power, it feels important that this novel, the first English-language translation by a female author from Cape Verde, can now reach a wider audience — an audience that has much to learn from Salústio about the power of language to make freedom visible, possible, and perhaps always incomplete.

Lucien Darjeun Meadows is a writer of English, German, and Cherokee ancestry born and raised in the Appalachian Mountains. An AWP Intro Journals Project winner, Lucien has received fellowships and awards from the Academy of American Poets, American Alliance of Museums, Colorado Creative Industries, National Association for Interpretation, and University of Denver, where he is working toward his PhD.

This post may contain affiliate links.