If there is an indie literary culture, Joseph Grantham is one of its great tastemakers. Editor-in-chief of The Nervous Breakdown, co-editor (along with his sister Mik) of Disorder Press, and author of two books of poetry, Grantham is a man whose fans include Dennis Cooper, Scott McClanahan, Elizabeth Ellen, and all 800 residents of Woodland, North Carolina. By my lights, his rise heralds a shift in contemporary literature, away from pyrotechnic peacocking, away from sentimentality, away from very online cynicism, and toward a melancholy humor and honest decency we haven’t seen since Richard Brautigan.

If there is an indie literary culture, Joseph Grantham is one of its great tastemakers. Editor-in-chief of The Nervous Breakdown, co-editor (along with his sister Mik) of Disorder Press, and author of two books of poetry, Grantham is a man whose fans include Dennis Cooper, Scott McClanahan, Elizabeth Ellen, and all 800 residents of Woodland, North Carolina. By my lights, his rise heralds a shift in contemporary literature, away from pyrotechnic peacocking, away from sentimentality, away from very online cynicism, and toward a melancholy humor and honest decency we haven’t seen since Richard Brautigan.

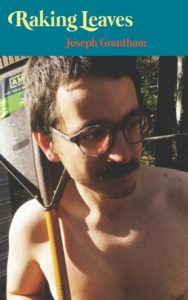

I spoke with Grantham about his latest book Raking Leaves (Holler Presents). This collection, a follow-up to his 2018 debut Tom Sawyer (CCM), charts the changes in Grantham’s life after he moved from New York to West Virginia (where he lived with the writers Scott McClanahan and Juliet Escoria) and, later, North Carolina (where he lived with the writer Ashleigh Bryant Phillips). With Ashleigh, he’s still moving, still writing about the significant and unassuming people he meets in significant and unassuming poems which are written “in plain American which cats and dogs can read.” At the center of Grantham’s work is an unwavering focus on everyday love and everyday death: another word for that “unwavering focus” is maturity. In the best sense, he’s the oldest young man you’ve ever read.

Michael Mungiello: Work seems to be a source of despair. In Raking Leaves you write, “I’ll never have a career.” But it’s when you’re at work that you write; you say “poems are coins” and they’re sort of your paycheck, what you earn while you’re there. Are you in some way inspired by the insane boredom of work?

Joseph Grantham: I’m glad you brought up the “poems are coins” poem. I think that’s my philosophy when it comes to poetry. The trouble with me having a philosophy is that I then have to articulate it. I don’t think of coins as having a monetary value, even though they do. I think of coins as trinkets, little things, each with a unique history, that get lost in your pocket. I was the cashier at the pharmacy where I worked in rural North Carolina and I spent a lot of time looking at the coins in the cash register. Specifically the dates on the coins. For some reason it fascinated me, still does, when I’d look at a penny, one cent, and see proof that it’d had a longer life than me. And probably a more interesting life, too. Another thing, most of my favorite poems are very short. Like the poem “December” by Ron Padgett. I like knowing that I can carry these poems around with me, in my head, like a pocketful of change, or I can literally carry around poems in my pockets, as I often did when I came home from work – because I wrote a lot of these poems on the prescription pads, and when the pharmacist, or a pharmacy tech, would walk by, I’d cram the poem into my white coat pocket because God forbid they catch me in the act of writing a poem.

But am I inspired by the boredom of work? I am more afraid of it than inspired by it. So I write at work to kill time and to amuse myself. But also, working at the pharmacy was interesting and surprising and foreign to me. I met so many different people that I’d never have met if I worked at a bookstore in San Francisco or New York. Like Darnell. Darnell would come in everyday and tell me about his life and not once did he buy medicine from me. All he bought was Dr. Pepper. Now I work at a bookstore in Baltimore. I do the returns. So I hide away in the back and mail all of my friends’ books back to their publishers because they didn’t sell well enough. It’s not as inspiring as the pharmacy but it’s calming in a similar way. It’s nice to have a small manageable task to complete over and over. I like boxing things up. I don’t think I’ll ever have a career because I don’t care enough about money and I don’t care enough about enough things. I want to make it clear that ‘not caring about money’ isn’t a heroic thing, I wish I cared more about it, I could help more people if I cared more about money, I could be a hero, but instead, I like to read books.

Raking Leaves ends, “please enjoy your life.” Do these poems come from a place of enjoying life?

I wanted the final line of Raking Leaves to be a command or a request. I wanted to ask something of the reader before they closed my book. That was the best request I could think of. I think it’s kind of a funny thing to demand. “Hey, you better enjoy your life, or else . . .” It’s also something I said to myself for a while. Maybe it worked. These poems come from a place of listening and observing and not thinking so much about Joseph Grantham. Of course, he’s still in there somewhere. What it comes down to is that when I was writing the poems in this book, I met a lot of people who were a lot worse off than me and who had a much better attitude and outlook than I did. I thought, if they can enjoy their lives, then I feel like I owe it to them to try to enjoy mine.

Drifting seems essential to Raking Leaves, not just in the “rambling man” Americana way but also in the Jewish sense of wandering (loosely evoked in “aunt sandy”). This is different from Tom Sawyer where you seemed to be writing against a sense of urban claustrophobia. Does literally moving have an influence on your work?

This book started as a joke at a dinner table in West Virginia and sort of drifted into a reality and became very much not a joke. Moving, and restlessness, has definitely had an influence on my work. I’ve never moved anywhere because I thought it’d help my writing, it’s always been a spur-of-the-moment thing. But moving to rural North Carolina was the best thing I could’ve done to myself and to my writing. It’s a good thing to be around people who don’t care about the same things that you care about. It’s a nice test. I learned how to talk to people and how to tell better stories. Or I got better at these things. And I learned that I like going to the post office and walking around Walmart and Belk and Tractor Supply. I’m going to stay put for a while in Baltimore, but I’m glad I spent a couple of years bopping around the country. Another thing, no matter where you go, you will find people in that place who love it more than any other place and who think the next place you’re going to go is an utter downgrade. When I told people in San Francisco I was moving to Woodland, NC (population 800 or so) they were shocked and surprised and I had to explain why I was moving. When I told people in Woodland I was moving to Baltimore (population 600,000 or so), I saw the same shock and even some disgust, like Baltimore, what the hell’s in Baltimore?

With regard to the Jewish sense of wandering, and the “aunt sandy” poem in particular, that idea of wandering, or displacement, is always in my head somewhere because when you hear those stories from your family, they tend to stick with you. The night I wrote that poem, I almost tripped over one of my cats and hit my head on my kitchen counter. And that seemed like a big moment for the first few seconds after I regained my balance. Wow, I almost hit my head. And for some reason my thoughts went from that to my Aunt Sandy and the stories she told me about her mother surviving Auschwitz. I was worried when I wrote that poem that she’d think I was making a joke about it, but when she read it, she understood. She said that growing up, she couldn’t help compare any small trivial thing that upset her to the enormous atrocities that her mother experienced.

You’re one of the hardest working people in the scene today – The Nervous Breakdown, Disorder Press, and of course your own writing. Does your work as an editor inform your work as a writer? Do you feel like you have to “balance” them?

Thanks for saying I’m hard working. It doesn’t always feel that way. Editing has made me a better writer, and it’s given me good instincts, but it’s also made me a tired writer. There’s a constant wrestle happening in my head and there is a lot of guilt. The only thing that makes it all worth it is when you get to champion a story or a poem that might never see the light of day without your help. I’m serious. I’m not a literary citizen, or if I am, then I’m not a very good one. Whatever that means. I have a hard time working on something if I don’t care about it. So I guess if I edit something for someone, it means I care about their work. That’s probably a good thing. But one day I’d like to stop doing so much editing and focus more on my own work.

Have your feelings about death changed? In Tom Sawyer, death seems to personally menace the speaker but in Raking Leaves, death is just part of life: the dead are fondly remembered but the speaker himself is content not to “jump off the balcony” but instead “go downstairs / and . . . eat the meatballs.”

When I was working on Raking Leaves, death was all around me, but it wasn’t a mysterious, menacing thing. It was just a fact of life. One day, when I was living with Scott McClanahan and Juliet Escoria, we were driving around their neighborhood in Beckley, and Scott kept pointing out different houses and saying things like, “That’s where so-and-so lived, he didn’t show up to work for a few days and he was found dead in his bed, had a brain aneurysm.” It was like an impromptu death tour. And when I worked at the pharmacy, I’d talk to a customer one day and then a few days later I’d hear that that person was dead. There were suicides, heart attacks, overdoses. It was just part of daily life. A lot of people die. When you’re in a big city you can distract yourself from real death, but in small towns it’s pretty apparent when so-and-so doesn’t show up to work. Funerals are part of the culture. I didn’t think of it like that when I was writing that poem, but you’re right, I kind of had to suck it up and eat the meatballs and stop being so afraid of death. I didn’t have a choice, it was right in front of me everyday.

Are your most important influences dead or alive? Tom Sawyer had more poems to Leonard Michaels and Charles Bukowski while Raking Leaves has almost exclusively first-name basis poems (like the great “rhonda”).

Leonard Michaels was a huge influence on me when I was in college. I had never read Bukowski up until about a year and a half ago when I was working at City Lights and one of my favorite coworkers, Don, talked him up to me. And I think people forget that City Lights published a lot of Bukowski and he’s very much a part of City Lights’s history. So I read Post Office, and what’s great about Post Office is that it’s about working an awful job, and I was new at City Lights and I think I hate all jobs for the first couple of weeks because I’m scared to learn new things and I think I come off as an idiot, so the book was comforting. Turns out, working at City Lights was a good job. But I wrote about Bukowski in my first book without ever having read him because an old coworker of mine at a different bookstore made some snotty remark about him and it rubbed me the wrong way because I don’t like looking down on people based on what novels they read. You could do a lot worse than Bukowski. For example, business books. Give me any Bukowski poem over How To Win Friends and Influence People, any day of the week. I don’t like looking at business books, I don’t like shelving them. But enough about all that. I’m lucky that most of my influences are alive and well. Of course, I just lost one of my biggest influences when Stephen Dixon died a month ago. Thankfully he left behind such a large body of work and many readers are now discovering him for the first time. But when I was putting together Raking Leaves, I kept thinking about all of the people in my little town and how many of them were larger than life. I wanted to tell people about my 93-year-old chain smoking doctor, and about the doomsday prepper’s bunker I drove by every week, and about my girlfriend’s sister’s state trooper boyfriend. I want people to go to Woodland, North Carolina and meet my girlfriend’s mom, and I want people to drive to Ahoskie and eat at Los Amigos. These people, and their stories, influenced me more than any book I’ve read and I’m grateful to them. The people and places in this book matter very much to me. When I look at this book, I sometimes see it as a photography book, except that the poems are the photographs.

Your bio reads that you “live in America.” You have poems here about the “death of America” – its corporatism and hellish politics. Why is this national scope important to you as a poet who also writes in the kind of highly personal style where poems are addressed as little letters to individual friends and loved ones?

I never thought the national scope was important to me but then I remembered that I’ve never had the good fortune to leave North America. I’ve never traveled out of this country, save one time when I was a kid and spent a few days in Vancouver. So as much as I want to whine about how awful this country is and how much I hate it, I also have to acknowledge that I literally do not know anything else. I’ve never set foot in another continent. That’s just not something I’ve been lucky enough to do yet. Maybe someone will read this interview and buy me a plane ticket. Wouldn’t that be nice? America is everything and nothing to me all at once. And of course everyone’s America is unique to their experience. So the death of my America might be the birth of someone else’s America. All I know is that the night that this book began, a man shot up a concert in Las Vegas and killed 58 people. And then a few weeks later a man went into a church in Texas and killed 26 people. And on and on and on. And I spent a lot of time sitting on a porch and staring across the street at a foreclosed house and it felt like something was in the process of dying and for a little while I called that something America. The longer I worked on this book, the smaller the scope became. I stopped thinking about politics or large statements about life in America, and instead focused on individuals with who I shared meals, and to who I sold drugs, and, in the case of Dr. Stanley, who I let check my lymph nodes.

Michael Mungiello is from New Jersey. His Twitter is @_______Michael_.

This post may contain affiliate links.