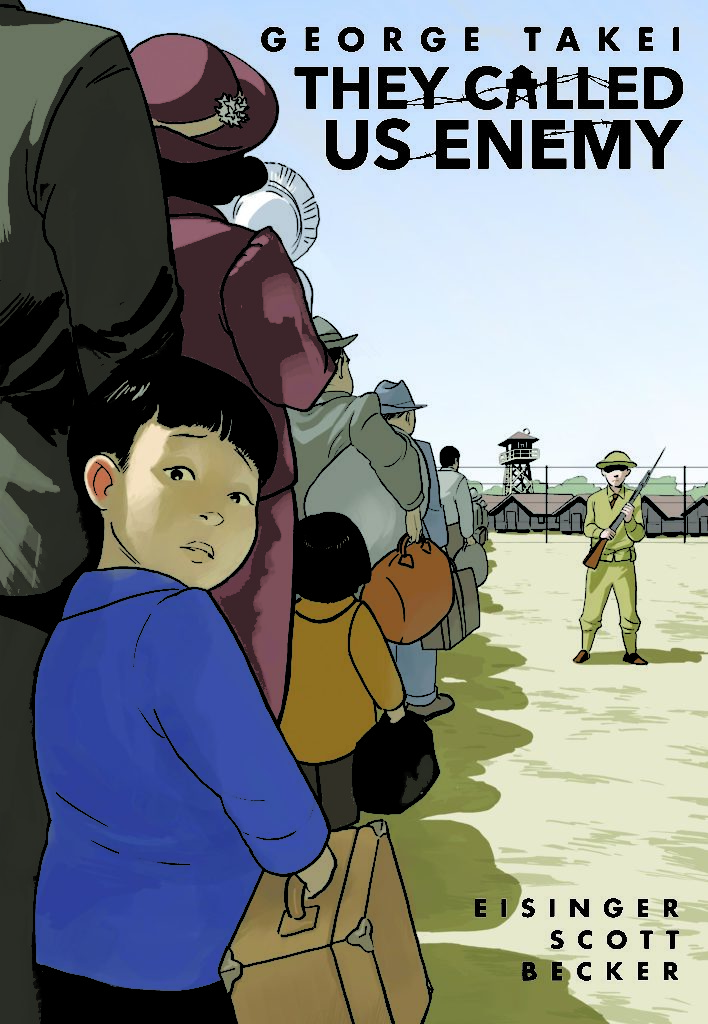

IDW has just published George Takei’s graphic memoir for young adults, They Called Us Enemy, the story of his early childhood spent in an internment camp during World War II. (The book was co-written by Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott. The artist is Harmony Becker.) It details Takei’s personal memories of one of the great moral atrocities of twentieth-century America. It wasn’t all traumatizing. He remembers the small wonders he discovered as a child. But the book also tells the story from his parents’ point-of-view and the moral dilemmas that faced camp internees. Japanese-Americans were asked to sign a loyalty oath in which they (1) offered to fight in the U.S. Armed Forces and (2) declared their loyalty to the United States government. His parents were both “no-nos.”

IDW has just published George Takei’s graphic memoir for young adults, They Called Us Enemy, the story of his early childhood spent in an internment camp during World War II. (The book was co-written by Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott. The artist is Harmony Becker.) It details Takei’s personal memories of one of the great moral atrocities of twentieth-century America. It wasn’t all traumatizing. He remembers the small wonders he discovered as a child. But the book also tells the story from his parents’ point-of-view and the moral dilemmas that faced camp internees. Japanese-Americans were asked to sign a loyalty oath in which they (1) offered to fight in the U.S. Armed Forces and (2) declared their loyalty to the United States government. His parents were both “no-nos.”

The story of the internment camps continues to test the faith of believers in American democracy, a faith that is, of course, being tested on a daily basis by the current occupant of the Oval Office. It forces American liberals to consider the limits of liberalism. In Star Trek, Takei’s Sulu and his fellow crewmembers inhabit a future in which humanity has achieved something akin to brother- and sisterhood, a respect for plurality, and an instinct for non-violence. Their values are questioned. They make compromises. They face their shortcomings. In the decades since Star Trek, Takei has become an ever more active non-violent warrior for social justice. We love him not only because he managed to carve out a second career in his late age as an internet celebrity, but because he seems to live the life we wish all such icons would live. He is Sulu.

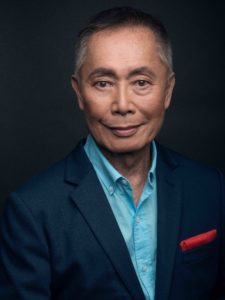

What is George Takei like? He’s gentle and personable. He liked the idea of being interviewed by a comics scholar. His husband, who is also his agent, had worked hard to fit me in for an hour-long interview on a Thursday afternoon in Seattle, where he was on book tour. George Takei’s voice plays several keys on the lower end of the scale. He’ll hit the boom and find the lilt when necessary. It has a softer character in person. He’s spent a life perfecting his instrument and he understands the power of restraint.

If it had gone on even longer, it could have ended in extermination. These camps wouldn’t have the reputation as internment camps, but as Auschwitz.

Extermination camps.

I believe that’s where it could have gone.

In fact, there were some people who feared that might have happened.

At what point in your life, did you look back and realize that’s what could have happened?

When I was a teenager, I became very curious about my childhood incarceration. I became a voracious reader. History books galore. I couldn’t find anything. It was back in the fifties. I read civics books. I couldn’t find anything mentioned about this in the civics books. But I found the ideas of American democracy intensified my curiosity. If we believe that all men are created equal, in equal justice within the law in a nation ruled by law, then how come [this happened]? And there was nothing I could find that was written. And so, after dinner, I had a conversation with my father.

And I realize now what an extraordinary man I had in my father. Because I learned that other Japanese parents of my father’s generation didn’t share their experience in camp with their children or their grandchildren. There are Japanese-Americans, younger Japanese-Americans, who don’t know anything about their parents’ or their grandparents’ lives, other than the fact that they were in camp. I developed a Broadway musical on the internment and so many Japanese-Americans came back stage to tell me how much they were moved by the story. And their parents were in camps. I’d ask them, “Which camp were they in?” And their faces were blank. I’d give them clues. “Was it in Wyoming or Arkansas? Or the desert of Arizona?” But they had no idea. They didn’t know anything except that they were in camps. So I knew that this was an important story to share.

Back to my father. When I engaged him in conversation, he shared with me his anguish. He said the thing that tore him apart the most was to see his three children and the barbed wire beyond, and the whole uncertainty.

Did he live in fear of extermination? Did he think it was headed there?

He never said that. As a matter of fact, in camp they protected us. He told us when we first arrived in Arkansas, “This was a long vacation.”

But did he himself ever fear that, at any point?

He did not. He said there was uncertainty. And maybe the uncertainty included that, but he never shared that with me. I heard that from other people much later on.

So how old were you when you found that out? Were you a teenager?

Teenager. I found other people who shared that that’s how they felt. Later on, when scholarly books were done, they talked about the game plan. They wanted us to be incarcerated so that we could be used for prisoner exchanges. And if they wanted to get [the Americans captured by the Japanese], they could have a bargaining chip. But this was much later.

Written by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, & Steven Scott, with art by Harmony Becker

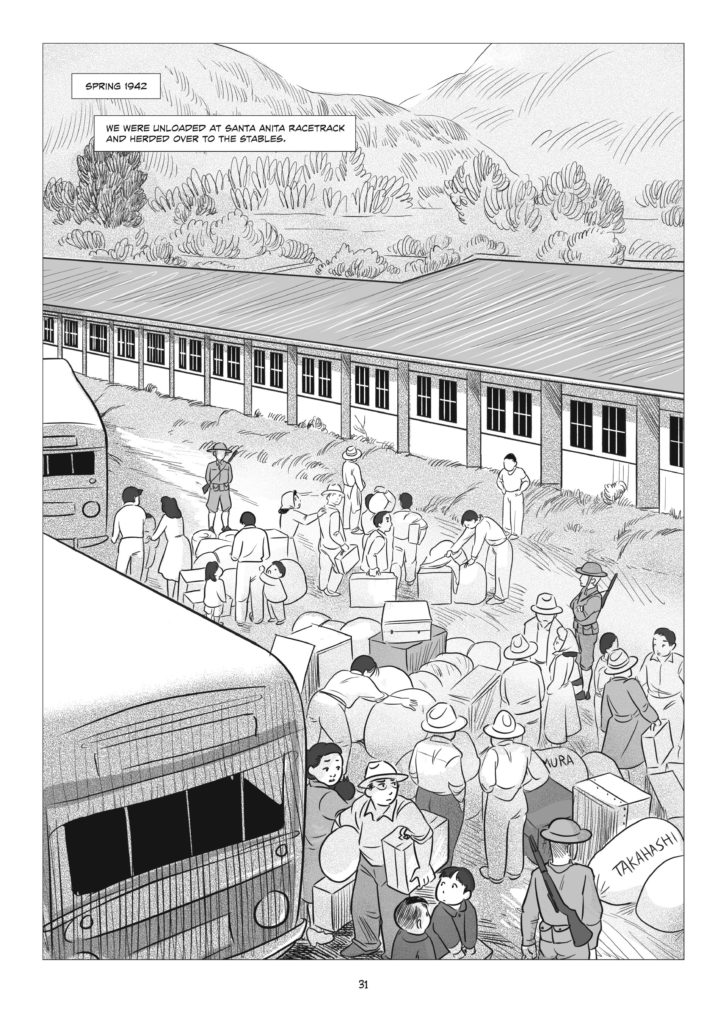

The American soldiers [in the book] are not ogres. They’re not comic-book supervillains. A lot of them are very nice kids.

Yeah. I remember the song they were singing. One of the MPs was always singing, [sings] “Shoo fly don’t bother me, / shoo fly don’t bother me, / shoo fly don’t bother me, / For I belong to Company C.” That kind of song. And some songs remain embedded in your memory. I saw them just as policemen in the neighborhood.

You have a story in here about a gentleman who is carrying a rifle. You touch the rifle. He jokes with you and he helps you onto the train.

And I remember that. Those were my real memories. I wanted to include my reality and draw the parallel with the reality of my parents.

As an eighty-two-year old man, how do you feel about that American soldier?

Wars are fought by the little people. The decisions are made by the elite of society. And that’s why I’m against warfare anytime. We got to have differences settled by diplomacy. World War II was a world war fought against Japan, Germany, and Italy. Seven decades later, they’re the strongest allies that we have in the Pacific and Europe. Right now, their economies are going down, but they’re still strong allies. What was it all about, ultimately? Tens of millions of people died. Terrific destruction is wrought on civilizations. What was the killing all about? And that killing was done by people who had nothing to do with the decision-making.

So you feel no anger against that soldier?

It’s pointless. I’m not a veteran, but I know veterans who fought in the Vietnam War. Some of my relatives are veterans who fought in wars. I don’t have that kind of black-and-white [outlook]. When I was a child, I saw as a child. As an adult, I see the larger issue. Wars are fought by the little people who have nothing to do with the differences between the people who get them killing each other. War is madness.

And that includes the people who are guarding these camps.

[My father and I] had many, many long, sometimes heated discussions. I was an idealistic kid and I said things that I know hurt my father. One still haunts me. We were going back and forth and I said I would have done this and I would have done that. [He said,] “Yes, but they were pointing guns at me. I had to think about your mother, you, your brother, and your sister. If something happened to me what would have happened to you guys.” I understood that. But it was against what the United States was fighting for. Our ideals. So we kept having this back and forth.

He said, “Despite all we went through, American democracy is still the best system in the world.” I can say that now [too]. I didn’t feel that way then. But this is the most difficult form of government as well. The easiest form of government is authoritarian dictatorship. You give it over to the boss and you just let him make the decisions. In a people’s democracy, we have to participate.

I said, “Look at the civil rights movement,” which was going on in the fifties. “They’re participating and they’re being attacked by dogs and firehouses. That’s not the American way.” “Yes, but you’ll see later on,” [my father said]. And there was integration.

Democracy works in steps and processes. And you have to deal with history incrementally. And one Sunday afternoon he said, “I’ll show you how it has to work.” And he drove me to the Adlai Stevenson for President campaign headquarters.

There was a word that was used to describe the Japanese as an explanation for why they should be sent to camps and that word was “inscrutable.” There’s a long history in Hollywood of the “inscrutable Asian.”

Not only Hollywood. The Yellow Peril. That’s where yellow journalism came from.

And what was so scary about them supposedly was that they were robotic. They kept their emotions and ideas hidden.

And they had a language problem. And they didn’t understand. And rather than be inscrutable, they held back their misunderstanding.

And the idea was that they were hiding something from us.

And that was used by Earl Warren, who went on to become a great “liberal” [makes air quotes] Supreme Court chief justice.

When you became an actor was that one of the stereotypes you were fighting against?

[When I wanted to be an actor], my father said to me, “Look at what’s on tv and on the radio or on stage or at the movies. Don’t do anything to embarrass me.” And I made that pledge to him that I would not. And I was lucky in many ways when I began my career…My first feature film [was] with none other than Richard Burton. My scenes were with Richard Burton and I was over the moon. I turned down other roles that seemed to be stereotypes.

Were any of them the inscrutable Asian?

The ones I turned down.

I had a Japanese-American agent who was an in an arena that many Japanese-Americans back then did not go into. He came up to me and said, “George, I got you a part in a big movie. Your career is beginning, but what you need is a big box office success. It’s box office that’s going to determine how your career goes. It’s a Jerry Lewis movie. It’s a comedic role. It’s something of a stereotype.” I said, “Look, I’m not going to do that. I made that pledge to my father.” He said, “George, I implore you.” Jerry Lewis is the biggest box office star in Hollywood at this point. It was the sixties. His movies were always number one. And [my agent] said, “It’s going to be very difficult for me to sell you if you turn down a Jerry Lewis movie. He wants you. He saw you in X,Y, and Z. He wants you. I urge you strongly to reconsider your position.” And because of that strong persuasion I did it. And I regret it to this day.

From They Called us the Enemy, Written by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, & Steven Scott, with art by Harmony Becker

You speak very admiringly of both the people who refused to sign the loyalty oath and went to prison as well as the people who joined the US Army.

My parents were both no-nos.

You don’t say what you think about the radicals, the people who swore allegiance to the Emperor, who decided that if this is how you’re going to treat us, this is how we’re going to be.

And that’s understandable too. It was an endless series of goading, insults…And the loyalty questionnaire itself.

We’re Americans. Born, raised, educated and like most Americans, [the Japanese-Americans] rushed right to recruitment centers right after Pearl Harbor to volunteer to fight for this country. That’s an act of patriotism. Yet this government sees them as an enemy and denies them military service, and then categorizes them as enemy aliens. [It’s] truly irrational. It’s crazy.

But you don’t consider [the radicals] heroic in the way you understand [those who refused to sign a loyalty oath and went to prison or those who signed the loyalty oath and fought for the United States] as heroic.

But I understand them as human beings. One outrage after another.

The Black Panthers, too. Fearsome people. You know who they were?

Of course.

Before your time. And they were radicalized. They did horrible things. But they come from a whole history of horrible things [done to them].

As a human being, I understand how they became radicalized. Some of them had volunteered to fight for this country. And now [the government is] going to say that [those same people] will rise up and fight for their country’s adversary. It’s a crazy world and they are reacting in the same crazy and irrational way.

You can question the purity of the integrity of the ones who went to fight. I admire those who took a principled position and paid the price for it. They fought on battlefields too. Their battlefields were behind the tall, concrete walls of federal penitentiaries. You can imagine the kinds of assaults and attacks that they had to put up with.

And they had no idea how long it would last.

Exactly. So those are the pure, principled people, maybe foolishly idealistic in another sense. But I admire them more for their guts and their purity. I admire the ones who fought. Because of their heroism, things started to change for us in this country. I owe a great deal to them. But my greater respect goes to those who took a principled stand and paid a high price for it.

You think it was a harder to take the principled stand than to go to war.

I think so.

There are stories coming out of the Southern border, and I hate to put hierarchies…

There is a hierarchy. This is a new low.

It’s a new low because it’s child separation…

And it’s evil. I mean, to put children in those filthy, disgusting cages. Human waste. A cage meant for twenty people holding 100 young people, literally piled on top of each other.

What modes of resistance do you recommend in a situation like this?

Well, it’s not the dilemma that Japanese-Americans faced in 1943 when the loyalty questionnaire came down.

What would you recommend for people who are going through this now?

The human condition is varied: the circumstances, your own personal makeup, your sense of responsibility to loved ones. You can’t make a sweeping [statement]. “This is right. This is semi-right and semi-wrong.”

You say that many Japanese-Americans didn’t want to talk about the [camps]. There’s nothing unique to Japanese-American culture about that. I hear it all the time…

From survivors of the Holocaust.

I heard an Indian woman at a conference a few weeks ago who said that her parents had told her you must never discuss the horrors that beset your tribe.

It’s so important that they share it. The next generation can participate in preventing that from occurring again. But as a human being, having gone through that meat grinder, to go back to the anguish and the heartrending experiences that you had…

It’s misplaced shame.

Yes it is. The real shame are the perpetrators, but [victims] are made to feel that they are ashamed.

I hate the term “Japanese internment camp.”

It’s incarceration.

No, no, no. Japanese. If you know the English language, Japanese internment camps were run by the government of Japan. We [were] American citizens of Japanese ancestry, imprisoned in our country, the United States of America, [as] ordered by the president of the United States. There was nothing Japanese about it. We were of Japanese ancestry, but it was the American internment of American citizens. It’s another one of my campaigns to have them say Japanese-American Internment Camps. I believe [“Japanese internment camps”] was a term coined by the United States government to distance themselves from their guilt.

Paul Morton is a lecturer in the Department of English at the University of Washington in Seattle, where he received a PhD in Cinema Studies. He is currently at work on a book on the animation industry of the former Yugoslavia, as well as a lengthy study of Jules Feiffer, America’s first literary cartoonist. You can contact him at [email protected]

This post may contain affiliate links.